Climate change represents one of the greatest and most challenging issues facing our world today. It’s not merely a term we hear on the news or see in the media—it’s a pressing reality with tangible impacts worldwide. Recent data from NASA highlights the pressing need for greater awareness and action on climate change.

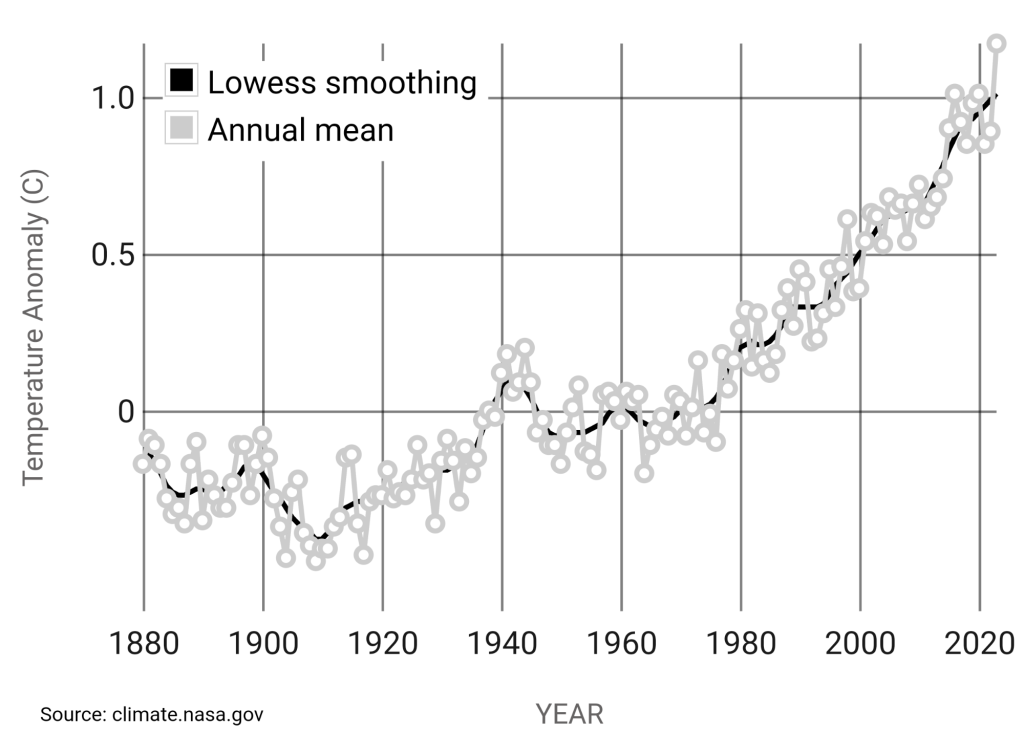

According to NASA’s 2023 Global Temperature Report, the accompanying graph illustrates changes in global surface temperature relative to the long-term average (1951–1980). Significantly, Earth’s average surface temperature in 2023 reached its highest level since records began in 1880, underscoring the rapid pace of warming over recent decades.

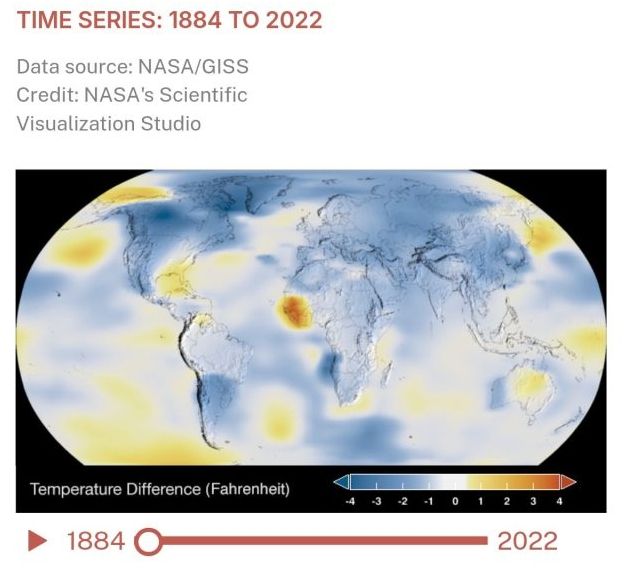

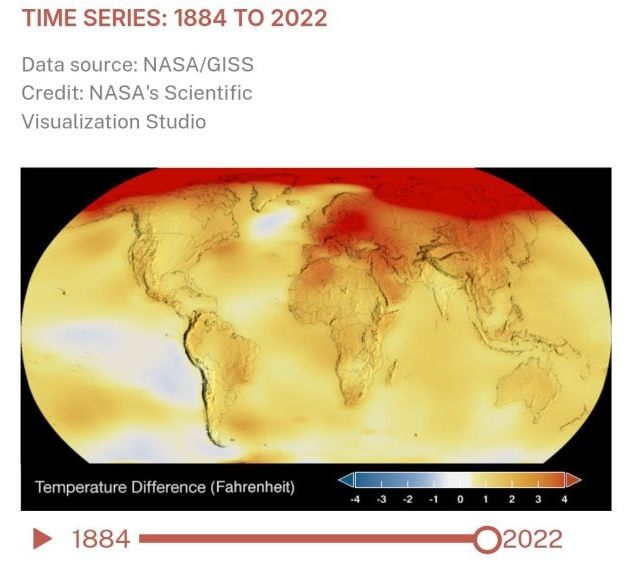

The following NASA’s animation displays shifts in global surface temperatures, with dark blue representing cooler-than-average regions and dark red indicating warmer-than-average areas. Notably, cooler (blue) areas predominated before the 2000s, while extensive warming (red) has become more pronounced, especially after 2020. The animation emphasizes the stark increase in warm regions, culminating in record-high temperatures seen in 2023.

Despite the overwhelming evidence, many people around the world still doubt the existence or severity of climate change, with notable segments of the population in denial, especially in the U.S. and some European countries.

For example, recent data from a University of Michigan study revealed that nearly 15% of Americans reject the reality of climate change, often influenced by political affiliations and scepticism of scientific information. This number has remained steady despite increasing scientific consensus and real-world impacts, like extreme weather events, that are exacerbated by global warming.

This denial is not just personal but often reinforced by social media, where misinformation spreads quickly and connects people with similar views, creating closed networks that resist scientific evidence.

Addressing this gap in climate change understanding is critical because those in denial may resist policy measures necessary for environmental crisis mitigation. Education that effectively communicates the science behind climate change and its implications can help bridge these gaps, and new technology can represent a valid tool for this.

Immersive Learning through Virtual Reality

Virtual Reality (VR) could revolutionize the way we educate the public about climate change, providing immersive experiences that drive home the urgency and scale of the crisis.

By using VR to showcase or simulate real-world climate scenarios, we can make the impacts of global warming more tangible and relatable, particularly in regions that are difficult to access, such as areas suffering from desertification or remote ice caps, providing a vivid perspective of the climate crisis from places that many may never visit.

Could this technology be the key to breaking through the misinformation barrier and fostering a greater commitment to sustainability?

As we consider this question, it’s clear that VR offers a powerful tool not just to inform, but to emotionally engage people in the fight against climate change. It provides an immersive way to visualize distant and often overlooked environmental changes, making these issues more personal and urgent.

Could VR help foster empathy for regions most affected by climate change by immersing individuals in these realities?

By bringing distant environmental challenges directly into people’s lives, VR could deepen understanding and drive action.

This potential suggests that VR could significantly reshape how we engage with climate issues, transforming awareness into meaningful change.

But How Does It Work?

Research into the psychology of images reveals their profound impact on memory and engagement.

People tend to remember information better when it is presented visually rather than textually, a phenomenon known as the Picture Superiority Effect (PSE).

The Picture Superiority Effect is a cognitive bias that explains why images are more likely to be remembered than words. This occurs because images engage both the visual and verbal channels in the brain, enhancing recall. Moreover, images possess more distinct visual features compared to text, making them easier to recognize and remember. Additionally, visuals tend to elicit stronger emotional responses, which further boosts memory retention. This combination of distinctiveness and emotional resonance makes images an especially powerful tool for communication (The Behavioral Scientist, 2023).

Psychologically, our brain processes images and text differently, with visual content often having a more significant impact on both memory and emotional connection. Visuals allow us to empathize and immerse ourselves in different situations more effectively.

This is where Virtual Reality (VR) comes into play. VR has the unique ability to transport users to environments that are distant or hypothetical, offering an unparalleled sense of presence and engagement.

By immersing people in realistic, yet distant, scenarios, VR has the potential to create lasting awareness about issues like the climate crisis, engaging both the mind and emotions in ways that traditional media cannot (Bonn Institute, 2023).

Case Study: “This Is Climate Change” VR Documentary

In this section, I reflect on the personal experience of watching the VR documentary This Is Climate Change.

This immersive, four-part series uses virtual reality to confront viewers with the stark realities of climate change, offering a powerful and emotional journey through some of the most affected environments on Earth.

While each episode presents compelling narratives, I would like to specifically focus on two of them: Melting Ice in Greenland and Famine in Somalia.

These segments represent, in many ways, complete opposites—like fire and ice, hot and cold—but are deeply interconnected through the devastating issue of rising temperatures. On one side, the ice in Greenland is melting at an unprecedented pace, contributing to rising sea levels and altering ecosystems worldwide. On the other, Somalia is grappling with extreme desertification, where scorching heat and lack of water are fuelling famine and displacement.

My Visual and Hearing Sensations

The VR experience heightened my sensory engagement, immersing me deeply into the two contrasting worlds. The overall experience went far beyond what words can do to describe those situations, tapping into emotions and physical sensations that traditional communication ways cannot replicate in the same way.

In Famine, the journey begins on a van traveling through a desolate, barren landscape in Somalia. From the very start, the feeling is one of overwhelming devastation and emptiness. It feels as though life has abandoned the land; nothing seems to be alive. The sensation is haunting, like being dropped into a dystopian future of death and desolation. The paralyzed sky looms above, still and suffocating, a pale white-grey hue that feels both heavy and unreal, mirroring the lifelessness below.

The vulnerability of people, especially children, is palpable when entering the hospital, even without the need for words. There are no interviews or constructed narratives, yet the visuals alone speak volumes. Lines of people wait silently for a truck delivering precious water, their desperation tangible. It almost feels like you can sense the dry, warm wind brushing against your face as you look around with the VR headset. The colors are muted, blurred, and as dry as the ground itself—dominated by shades of brown and white, capturing the severity of the drought.

In contrast, Melting Ice presents a different sensory experience, though no less alarming. The VR places you directly in the snow, under a crisp blue sky in Greenland.

Researchers greet you at their camp, sharing grim updates: since they began measuring in 1990, Greenland has experienced a +4°C temperature increase every single year. This statistic hangs heavy in the air, as you’re led through this icy, yet fragile, landscape.

A boat ride offers an expansive view of the land of ice, revealing an unexpected truth: there is far more water than you might anticipate. The icebergs appear fragile, dirty, and brown, their once brilliant white color dulled by heat and melting. The ice cracks and collapses before your eyes, crashing into the water—a visual and auditory reminder of the damage unfolding. Small rivers cut through the ice, an unnatural sight that underscores the irreversible changes.

Here, the sensory overload of water contrasts sharply with the parched emptiness of Somalia. Where you expect massive, unbroken glaciers, you instead see endless pools of blue water beneath a sunny sky. The visuals carry a dissonance: the sheer volume of water is alarming when juxtaposed with the desperation in Somalia, where every drop is precious.

Through these vivid sensations that speak much louder than words, This Is Climate Change presents two sides of the same crisis. While the settings—fire and ice, hot and cold—are worlds apart, they are connected by the underlying issue of rising temperatures.

The immersive VR experience not only brings these realities to life but also bridges the gap between data and emotion, offering a visceral understanding of the climate emergency. From my point of view, it leaves a haunting impression: a world where glaciers melt away and lands turn barren, both victims of the same global catastrophe.

Virtual Reality To Develop Other Realities

In his work The Digital Street, Jeffrey Lane highlights the interplay between physical and digital spaces in shaping community dynamics and interactions. Specifically, the study delves into how the “networked street” operates, bridging the physical environment of Harlem’s streets with its digital counterpart, as observed through social media platforms and mobile devices. Lane’s ethnographic approach emphasizes the importance of understanding both the spatial and relational dynamics of the community, offering insights into how digital tools can extend the reach of traditional ethnographic methods.

Similarly, VR offers a unique opportunity to enhance ethnographic studies by providing researchers with immersive, three-dimensional representations of environments and social dynamics. While Lane relied on digital communication platforms to access and observe Harlem’s networked street life, VR can simulate such spaces, enabling researchers to engage with and analyze cultural and social phenomena from a perspective that feels more “lived.”

For instance, VR could recreate the networked interactions Lane describes, allowing researchers to virtually walk through digital representations of street life, observe reenacted conversations or maybe even use avatars, connecting physical and virtual ethnographic practices.

By combining Lane’s insights into the digitization of street life with VR’s immersive capabilities, ethnographers can further explore complex socio-spatial dynamics, capturing both the sensory and relational aspects of communities.

This integration underscores the potential of VR to serve not just as a storytelling medium but also as a transformative tool for development-related ethnographic studies, allowing researchers to contextualize and communicate their findings in ways that traditional methods might not fully capture.

In their article “Immersive Storytelling and Affective Ethnography in Virtual Reality”, Ceuterick and Ingraham explore how virtual reality can enhance ethnographic encounters by immersing the viewer in sensory experiences. They argue that VR’s potential lies not just in offering new perspectives but in facilitating emotionally resonant engagements with marginalized communities. By positioning the viewer in the midst of an unfolding narrative, VR blurs the boundaries between proximity and distance, creating an experience where the viewer can feel both connected and distant from the subjects’ lives.

A strong example discussed is Traveling While Black, an Emmy-nominated VR film that takes viewers through the historically significant Ben’s Chili Bowl in Washington D.C. This VR film places audiences in a space that has been a sanctuary for Black Americans, providing a visceral experience of the racism and systemic issues faced by Black travellers. The article highlights how VR storytelling can evoke empathy and understanding by situating the viewer directly within the narrative, such as in this instance where they are physically seated at the diner, unable to move—mirroring the lack of freedom felt by Black Americans under the weight of institutionalized racism.

At first glance and after following some recent studies, Virtual Reality may appear to be an ideal tool for improving actual reality experiences, presenting itself as an all-positive innovation. However, while VR has immense potential, its effectiveness and inclusivity require deeper consideration.

Is Virtual Reality truly an equalizing tool for social studies and development?

Not All That Glitters Is Gold in Social Research and Development

While VR offers compelling opportunities for immersive storytelling and understanding, we must critically examine some of its possible limitations.

Bell Hooks, in Writing Beyond Race, argues that access to new technologies is not universal, as systems of power often decide who controls and also who can benefit from these tools. VR, like many technologies, is shaped by these inequalities, with white power still often prevailing in content creation and access.

This reflects broader issues in the development world, where power imbalances keep excluding marginalized voices, whether in terms of technology access, representation on media and more.

VR may offer new ways to share stories and educate people on changes happening all around the world, but it also raises questions about whose stories are told and who controls the narrative. As Hooks emphasizes, true inclusivity in technology means addressing these power imbalances: ensuring access and equal participation in the creation and of digital content to share.

In conclusion, while VR has the potential for transformative impact, its use must be critically examined to ensure it does not merely reinforce existing disparities.

And you readers? What do you think about virtual reality to change reality?

Aurora L.

Bibliography

Bell Hooks. (2013). Writing Beyond Race: Living Theory and Practice. Routledge.

Bonn Institute (2023). Why images are so powerful — and what matters when choosing them.

https://www.bonn-institute.org/en/news/psychology-in-journalism-5#how-the-brain-processes-pictures-

Ceuterick, M., & Ingraham, C. (2021). Immersive storytelling and affective ethnography in virtual reality. Review of Communication, pp. 9–22.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/15358593.2021.1881610

Lane, J. (2016). The Digital Street: An Ethnographic Study of Networked Street Life in Harlem. American Behavioral Scientist, pp. 43-58.

https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764215601711

MIT Education (n.d.). This Is Climate Change – Visit The Project.

https://docubase.mit.edu/project/this-is-climate-change/

NASA (2023). Global Temperature – Vital Signs Report.

https://climate.nasa.gov/vital-signs/global-temperature/?intent

This Is Climate Change: Famine (n.d.). Video.

https://youtu.be/rJbPkFt-YIA?si=6TwOO321SaqdDqeT

This Is Climate Change: Melting Ice (n.d.). Video.

https://youtu.be/MwSLTGjPqG8?si=KtfjgO9jzGIPYKpU

University of Michigan (n.d.). Nearly 15% of Americans Deny Climate Change is Real, AI Study Finds.

https://news.umich.edu/nearly-15-of-americans-deny-climate-change-is-real-ai-study-finds/

Great text Aurora!

Indeed whose story is being told is a very urgent matter. I am actually quite perplexed today to see that people do not seem more worried about this question than they do. AI takes its information from what the majority says. Not only is this unfair to people who have less access to technology and less knowledge and capacity to be present in the online world, it is also a tremendous security threat as terrorist groups and regimes today exploit this to a maximum. Also, our efforts in European discourse (I live in Europe) to counter this seem to me aimed mainly at incorporating the views of groups who represent minorities in Europe but who are not necessarily minority groups in their region of origin. Which means we may never get any significant input from oppressed minority groups in certain regions because their oppressors’ voices are amplified in Europe while theirs are even further erased.