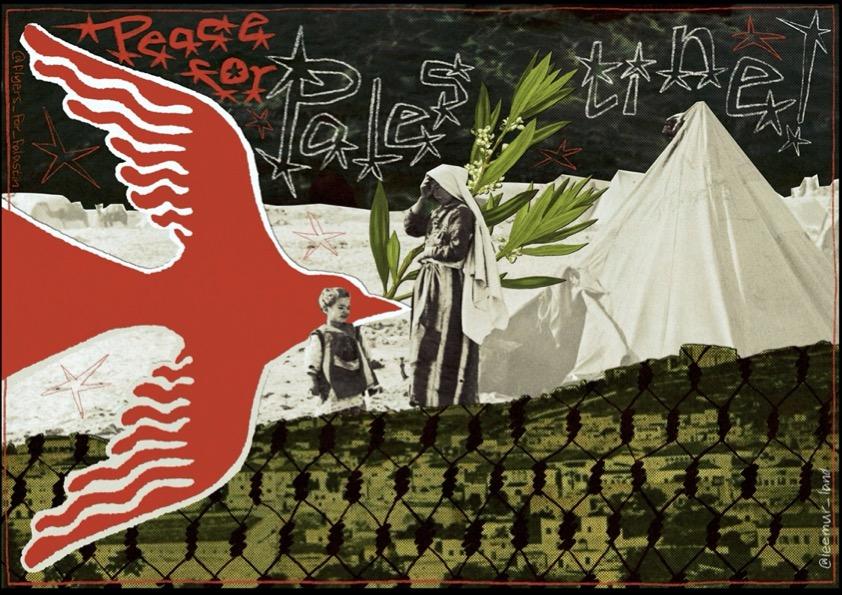

“Peace for Palestine”

Artist / Designer

@leemur_land

In this article, I will contextualize the events and insights from my previous exploration of pro-Palestinian protests in Athens within an academic framework, drawing on the works of scholars such as Barnett (2011), Brun and Horst (2023), Fechter (2023), and Salvatici (2020). By situating the grassroots activism and dockworkers’ strike within theoretical concepts like relational and everyday humanitarianism, this analysis seeks to interrogate the limitations of traditional humanitarian frameworks and highlight the transformative potential of decolonial and politicized forms of solidarity. The aim is to provide a deeper understanding of how such movements challenge entrenched systems of power and reimagine humanitarianism as a practice of justice, rooted in proximity, intersectionality, and resistance.

As indicated on my previous article that you are able to find here, on October 5, 2024, thousands of demonstrators gathered in Athens despite the rain, marching through the city to denounce military aggression in Gaza and express solidarity with Palestine. This mass mobilisation exemplified a growing trend of grassroots activism that challenges traditional forms of humanitarian response. Alongside street protests, dockworkers at the port of Piraeus took a bold stand by refusing to load munitions destined for Israel, an act that directly connected local labour struggles with global anti-imperialist solidarity.

This wave of activism in Athens provides a compelling case study to examine contemporary forms of humanitarianism, which increasingly move beyond classical, depoliticised frameworks towards what scholars term “relational humanitarianism” (Brun and Horst, 2023) and “everyday humanitarianism” (Fechter, 2023).

These frameworks focus on solidarity, proximity, and political engagement rather than neutrality and distance, offering new ways to think about the intersection of activism, humanitarianism, and global justice.

Decolonising Humanitarianism

Humanitarian responses have long been shaped by what Barnett (2011) describes as three historical “ages” of humanitarianism: imperial, neo-humanitarian, and liberal. Each phase reflects a dominant geopolitical framework, from colonial interventions under the guise of compassion to Cold War-era state-led aid and, most recently, the neoliberal commodification of humanitarian assistance. Today, grassroots movements like those in Athens represent a rupture from these traditions, aligning instead with calls to decolonise humanitarianism and reframe it as a tool for justice rather than control.

Athens’ pro-Palestinian protests illustrate a rejection of what Slim (2022) refers to as the “Swiss Model” of classical humanitarianism, which centres on neutrality and impartiality. While neutrality is often portrayed as the hallmark of humanitarian aid, it has been repeatedly criticised for its complicity in maintaining structural injustices (Terry, 2002). By taking overtly political stances—such as condemning Western imperialism and disrupting military supply chains—activists in Athens challenge these norms, situating themselves firmly within a decolonial framework of solidarity.

Everyday Humanitarianism and Grassroots Action

The actions of Athens’ dockworkers provide a striking example of what Fechter (2023) calls “everyday humanitarianism”—a form of engagement rooted in the lived experiences and moral convictions of ordinary people rather than institutional directives. By refusing to facilitate the shipment of munitions bound for Haifa, the workers bridged the gap between local labour rights and global anti-war movements. This act of defiance underscores a growing critique of traditional humanitarian actors, such as NGOs and INGOs, which, while essential, are often constrained by state funding and regulatory frameworks (Roth and Saunders, 2024).

The protests also reflect what Richey (2018) and Cantat and Feischmidt (2019) describe as “horizontal solidarities,” where self-organised movements operate outside formal structures to address the political dimensions of humanitarian crises. These movements are not only critical of state policies but actively resist them, as seen in the heightened police surveillance and detentions faced by activists in Athens. Such repression, while intended to silence dissent, often highlights the radical potential of grassroots mobilisation to challenge systems of oppression.

Relational Humanitarianism in the Greek Context

The mobilisation in Athens gains additional significance when placed within the context of Greece’s socio-political history. As a country with a strong tradition of resistance—against Ottoman occupation, Axis forces during World War II, and military dictatorship in the 20th century—Greece has a cultural memory of opposing imperialism and external domination. This historical backdrop informs the language and strategies of contemporary activism, with pro-Palestinian protests drawing on parallels between Palestine’s struggle for sovereignty and Greece’s own fights for independence and justice.

Brun and Horst’s (2023) concept of “relational humanitarianism” helps us understand how such movements connect local histories with global struggles. Relational humanitarianism emphasises proximity and connection over the distant paternalism of classical models. In Athens, this is evident in the explicit linking of Greece’s labour and anti-austerity movements with broader calls for Palestinian liberation, as seen in slogans like “Freedom for Palestine”. These expressions of solidarity highlight the shared nature of struggles against imperialism, militarism, and systemic inequality.

The Politics of Aid and Solidarity

The actions of Greek activists also serve as a critique of the broader political economy of humanitarianism, which scholars argue is deeply intertwined with colonial and post-colonial relations (Barnett, 2011; Salvatici, 2020). Mainstream humanitarian aid, dominated by high-income countries, often ignores the disproportionate burden placed on low-income nations in hosting refugees and managing crises (Mondon and Winter, 2020). By contrast, grassroots movements like those in Athens foreground the voices and agency of those directly affected, challenging the Global North’s monopoly on defining and delivering aid.

Pallister-Wilkins (2022) further notes that grassroots activism, particularly in Europe, is frequently criminalised when it challenges state or intergovernmental policies. The repression faced by Athens protesters underscores this dynamic, revealing the precarious position of self-organised movements that oppose dominant narratives of neutrality and legality. Yet, it is precisely this defiance that makes such movements a powerful force for reimagining humanitarianism as a tool for justice.

Towards a Transformative Humanitarianism

The grassroots activism for Palestine in Athens exemplifies a shift towards more relational and politicised forms of humanitarianism. By rejecting neutrality and embracing solidarity, these movements challenge the hierarchies and injustices embedded in classical humanitarian frameworks. They remind us that humanitarianism is not merely about alleviating suffering but about addressing its root causes—imperialism, militarism, and systemic inequality.

As the dockworkers of Piraeus and thousands of protesters in Athens have shown, grassroots mobilisation has the potential to transcend borders, linking local struggles to global movements for justice. In doing so, they offer a transformative vision of humanitarianism—one that is decolonial, intersectional, and unapologetically political.

References

Barnett, M. (2011). Empire of humanity. A History of Humanitarianism. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Brun, C., and Horst, C. (2023). ‘Towards a Conceptualisation of Relational Humanitarianism’ Journal of Humanitarian Affairs 5(1): 62–72.

Cantat, C., and Feischmidt, M. (2019). ‘Conclusion: Civil Involvement in Refugee Protection –Reconfiguring Humanitarianism and Solidarity in Europe’ in Feischmidt et al. (eds) Refugee Protection and Civil Society in Europe. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 379–99.

Fechter, A.M. (2023). Everyday Humanitarianism in Cambodia: Challenging Scales and Making Relations. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Mondon, A., and Winter, A. (2020). Reactionary Democracy. How Racism and the Populist Far Right Became Mainstream. London: Verso.

Pallister-Wilkins, P. (2021). ‘Saving the Souls of White Folk: Humanitarianism as White Supremacy’ Security Dialogue 52(1_suppl): 98–106.

Richey, L.A. (2018). ‘Conceptualizing “Everyday Humanitarianism”: Ethics, Affects, and Practices of Contemporary Global Helping’ New Political Science 40(4): 625–39.

Roth, S., and Saunders, C. (2024). Organising for Change: Social Change Makers and Social Change Organisations. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

Salvatici, S. (2020). In the Name of Others. A History of Humanitarianism, 1755–1989. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Slim, H. (2022). Solferino 21: Warfare, Civilians and Humanitarians in the Twenty-First Century. London: Hurst.

Terry, F. (2002). Condemned to Repeat? The Paradox of Humanitarian Action. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.