And there won’t be snow in Africa this Christmas time….

Hi there dear reader, hope you are doing well in these rather confusing and troubling times. In this post I want to delve a little deeper into the question of digital activism and whether it’s a case of doing good or just looking good, which is a core topic of debate in our Master’s programme.

My Instagram algorithm understands the sort of person I am. It knows I am part of the LGBTQ+ community. It knows I live in Denmark. It knows I spend far too much time looking at memes rather than doing work and it sure as hell knows my pro-Palestinian stance in the Isreal-Gaza war as it pushes pro-Palestinian content my way, mostly from accounts that I don’t follow, but largely also from accounts I do – both my personal network and from organisations such as Middle East Eye or Jewish Voices for Palestine.

It got me thinking more about how this aspect of digital activism fits in the the looking good or doing good debate – and you’ll have to excuse me if my blog post jumps quite dramatically from one topic to the next!

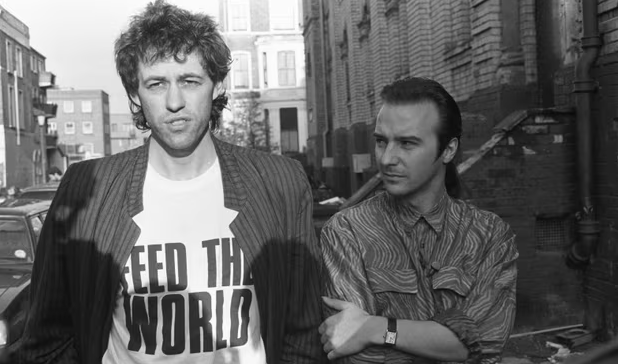

Long before the advent of social media, in fact long before our cultural and economic digitisation en masse, perhaps one of the most iconic examples of the ‘looking good or doing good’ phenomenon is Band Aid and their song ‘Do they know it’s Christmas?’. The title of the song alone is enough to send alarm bells ringing.

‘And the Christmas bells that ring there are the clanging chimes of doom, well tonight thank god it’s them instead of you’ (recently updated to ‘well tonight we’re reaching out and touching you’).

‘And there won’t be snow in Africa this Christmas time’. Honestly, almost every single word of the song is problematic, so I could go on – you get my drift.

Another iteration of this patronising tune (albeit catchy as hell) has just been released on November 25th; this time, a mash-up of all 3 previous releases from 1984, 2004 and 2014, produced by Trevor Horn (mid-70s, white, male, straight) into the ‘ultimate mix’.

Ed Sheehan whose vocals appeared on the 2014 version has made public his feelings about the new version of the song. Posting on his Insta, Sheeran commented: “My approval wasn’t sought on this new Band Aid 40 release and had I had the choice I would have respectfully declined the use of my vocals. A decade on and my understanding of the narrative of this has changed.” (The Guardian, Nov 2024).

I’m no Ed Sheeran fan, but he makes a fair point; the lyrics of the song have aged dreadfully. British-Ghanian vocalist Fuse ODG comments on fund-easing initiatives such as Band Aid: “while they may generate sympathy and donations, they perpetuate damaging stereotypes that stifle Africa’s economic growth, tourism and investment. By showcasing dehumanising imagery, these initiatives fuel pity rather than partnership, discouraging meaningful engagement.” He goes on to comment that the narrative needs to be reclaimed and that, “today, the diaspora drives the largest flow of funds back into the continent, not Band Aid or foreign aid, proving that Africa’s solutions and progress lie in its own hands.” – (The Guardian, Nov 2024)

I’m reminded of Wolfgang Sachs who says, ‘development is much more than just a social economic endeavour; it is a perception which models reality, a myth which comforts societies and a fantasy which unleashes passions’ (Quoted in Buzzwords and Fuzzwords, 1992 p.1).

And here lies the crux of the question. While Band Aid has raised over £150m since Bob Geldoff’s initial 1984 endeavour, driven by people’s passions to see an end to the Ethiopian famine, the deeper question remains: at what cost to Africa’s image and autonomy?

Good Intent or just good content?

Another aspect of this debate which has grabbed a few media headlines recently is MrBeast and his so-called philanthropy as performed on his extremely popular Youtube channel of the same name.

He is known for his fast-paced and high-production videos featuring elaborate challenges and lucrative giveaways. With over 330 million subscribers, he has the most subscribers of any YouTube channel, and is the third-most-followed creator on TikTok with over 104 million followers.

You needn’t watch more than 10 seconds of the following to get an idea of what this guy is all about…

Critics argue MrBeast’s charitable acts, often monetized through YouTube, blur the line between generosity and self-promotion, raising questions about sincerity. Former employees have accused him of fostering a high-pressure, toxic workplace, though he denies these claims. Some say his videos glorify wealth, set unrealistic expectations, or exploit participants for entertainment. His global outreach efforts have also been critiqued for perpetuating a “savior narrative” and lacking nuance. Despite these controversies, MrBeast remains a hugely influential figure in online entertainment and philanthropy.

MrBeast’s approach to philanthropy may reflect a belief that its primary purpose is to provide direct relief rather than address root causes—though it’s more likely he hasn’t deeply considered this distinction. Regardless, his medium constrains him: for his model to succeed, the philanthropy he showcases must be visually compelling, favouring individual interventions and tangible outcomes over upstream efforts like research or advocacy. (Rhodri, 2024).

Rhodri, writing in the journey of Philanthropy and Marketing goes on to comment that this issue is amplified in videos where MrBeast’s philanthropy targets countries in the Global South. The portrayal of recipients’ needs, combined with expectations of gratitude and underlying racialised power dynamics, creates a potentially uncomfortable and problematic narrative:

“At a time when many traditional NGOs and philanthropic funders are grappling with the challenge of how to avoid succumbing to “white saviourism” in how they understand and present their work, MrBeast’s willingness to make videos that unapologetically cast him as a white saviour handing out his largesse to groups of smiling African children may seem jarringly retrograde.” (p.5)

In fact, it was just last week that MrBeast appeared in headlines accused of exploiting participants, although he has retorted that such claims were “blown out of proportion” (BBC News, November 2024).

In September, Amazon and MrBeast were sued in the US over alleged mistreatment of participants on the set of their game show. The series, billed as the largest live game show ever, featured 1,000 contestants competing for a $5 million prize. While MrBeast has not formally addressed the claims, he responded to a question on X, saying, “We have tons of behind the scenes dropping when the show does to show how blown out of proportion these claims were. Just can’t release it now because it would spoil the games.”

And what about Palestine?

History is often shaped by ordinary individuals committed to peace and justice in equal measure to those who pursue war and conflict. Since the October 7 Hamas attack, Israel’s actions in Palestine have brought several activists to prominence, using social media to expose the brutal realities of the atrocities taking place.

Defying state propaganda, figures like Motaz Azaiza, Bisan Owda, Plestia Alaqad, Hind Khoudary, and veteran journalist Wael al-Dahdouh have shared devastating, heart-wrenching images directly through social media. Scenes of grieving parents mourning their children’s bloodied bodies have ignited widespread outrage—directed at Hamas, the Israeli government under Benjamin Netanyahu, and the complicity of the US, UK, and EU governments.

Politicians may control the narrative, as they gaslight the world with fake news, but the voices of activists are making a difference as they are amplified through social channels, particularly Instagram and TikTok.

From powerful speeches to heartfelt slogans about Gaza, digital activism takes many forms to amplify the voices of the marginalised. Whether through Mandela’s global impact, Azaiza’s Instagram posts, or Wayne Campbell’s grassroots work, activists bring awareness that inspires change. In every form, online, as well as offline activism remains a driving force for justice.

The world must remember that all lives matter equally—Palestinian, Israeli, Muslim, Jewish, Christian, black, brown, and white. As young Palestinians continue their fight, their courage and resilience light the path toward a more just and equitable world, urging us all to play a role in the pursuit of justice and equality.

In an article entitled ‘Gaza’s social media activists are a potent force for change in the fight against racism’, Kenneth Mohammed writes,

“Scorn towards social media is often justified – but in this instance, it is misplaced. We all use the “weapons” at our disposal to create change”. (The Guardian, Feb 2024)

We are not getting the full facts about Isreal’s atrocious war machine, ethnic cleansing and genocide via the main stream media, so people are turning more towards social media where they feel they are getting a more accurate picture of what’s happening on the ground.

Another example of how digital activism has proved successful in raising awareness for Palestinians is via the BDS (Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions) movement.

BDS focuses on ending Israeli occupation and settlement expansion, achieving equality for Palestinians, and recognising the right of return for the 7.3 million Palestinian refugees worldwide. Its widespread support has been largely driven by the promotion of Palestinian rights through online platforms.

Coca-cola, for example, has been on the BDS’s official list of boycotts given the Central Beverage Company, known as Coca-Cola Israel, which is the exclusive franchisee of the Coca-Cola Company in Israel, “operates a regional distribution center and cooling houses in the [Israeli] Atarot Settlement Industrial Zone.” (according to research by research by WhoProfits).

Since Isreal’s war on the occupied territories, and the increasing level of peaceful protest and the digital activism that goes hand in hand with the pro-Palestinian movement, there has been a renewed interest in the BDS movement.

There is now even a ‘genocide-free’ cola ‘Gaza cola’ which has been surging in popularity, particularly in the UK. Founded by Osama Qashoo, who fled Palestine in 2003 and who in 2001 co-found the International Solidarity Movement (ISM), an organisation that promotes peaceful direct action to resist Israeli occupation of Palestinian land, which Qashoo says was a forerunner of the BDS movement.

He says:

“These companies that fuel this genocide, when you hit them in the most important place, which is the revenue stream, it definitely makes a lot of difference and makes them think. Gaza Cola is going to build a boycott movement” that will hit Coke financially.”

He adds that he also wanted to create a product that was “an example of trade not aid”.

(al-Jazeera, Nove 2024).

All profits of which will be redirected towards the rebuilding of the the maternity ward of the al-Karama Hospital in Gaza City.

I’d say that none of this falls into the category of looking good over doing good. People really care about what’s happening in the middle-East with the pro-Palestinian and BDS movements gaining momentum due to Isreal’s atrocities.

A final thought…

The concept of “looking good or doing good” highlights the tension between authentic altruism and performative acts in development, aid, and digital activism. While campaigns often raise significant funds and awareness, their focus on optics—through viral moments, celebrity endorsements, or dramatic imagery—can perpetuate stereotypes, disempower communities, and prioritise donor satisfaction over meaningful impact. In an age of digital amplification, these strategies risk turning social causes into commodified narratives. On balance, there is a pressing need to re-evaluate how causes are communicated and funded, fostering approaches that emphasise dignity, partnership, and sustainable solutions over spectacle.

(Digital) activism, whether through art, music, social media, or grassroots organizing, remains a vital force for change (Karam et al., 2021)

In the case of the Israeli-Palestine war I can only speak for myself, but the horrors we’re witnessing on our screens are enough, or at least should be enough to make anyone stand up and look at the issue head on. And whether that’s a case of attending a march, re-posting content on social media, or even opening a conversation with family and friends who might usually see these topics as ‘out-of-bounds’, I think digital activism is playing a huge role in the overall movement right now.

As a final point of reflection, I’d like to draw you to a quote from chapter 17 of Deconstructing Development Discourse entitled ‘Public advocacy and people-centred advocacy: mobilising for social change:

“Many people claim that they are promoting or doing advocacy without really

thinking about what they mean by this. How many of its proponents know

that it is about actions that are rooted in the history of socio-political and

cultural reform? Few seem to go beyond the bandwagon syndrome to redefine

the concept and practice of advocacy in promoting social change.” (p.185)

Thanks for reading,

Joel

References

Andrea Cornwall and Deborah Eade, Deconstructing Development Discourse: buzzwords and Fuzzwords, 2010, Oxfam

Karam, Beschara; Mutsvairo, Bruce (eds.) (2021): Decolonising Political Communication in Africa-Reframing Ontologies Links to an external site.. Oxon: Routledge.

Davies, Rhodri (2024): Good intent, or just good content? Assessing MrBeast’s philanthropy, journal of Philanthropy & Marketing, 29(2), e1858.

Digital Activism in Perspective: Palestinian Resistance via Social Media: https://www.isjq.ir/article_89793_d41d8cd98f00b204e9800998ecf8427e.pdf

https://www.theguardian.com/music/2024/nov/18/ed-sheeran-i-wish-i-wasnt-on-40th-anniversary-version-of-band-aid-do-they-know-its-christmas

https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c5yxnddeyl0o

https://www.aljazeera.com/features/2024/11/23/genocide-free-cola-makes-a-splash-in-the-united-kingdom?utm_campaign=feed&utm_medium=referral&utm_source=later-linkinbio

https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2024/feb/20/gaza-palestinian-protesters-social-media-activists-fight-racism-inequality

Comments

2 responses to “Digital Activism: doing good or looking good?”

Hi Joel,

Thank you for this post, it is an important and deeply intriguing one. The unintended consequences of “looking good” instead of “doing good” can be widely damaging. I watched an interview of Fuse ODG on Piers Morgan’s show, Uncensored. He explained how perpetuating such demeaning narratives about the global south, just as Band Aid did, affects children with African heritage, their self-confidence and self-esteem is deeply reduced with the wide dissemination of such patronising narratives about the African continent.

I completely agree with you that there needs to be a re-evalution and accountability on how communication for development is done.

-Anita

Thanks so much for taking the time to read my post, Anita – really appreciate it! And I couldn’t agree more; I’ll certainly take a look at that interview you mention.

🙂

Joel