The study of Communication for Development (C4D) has certainly brought me out of the spectator seat and allowed me to see beyond the surface of social issues. I am particularly drawn to the exercise on interviewing techniques, where I could engage hands-on with the process. This post reflects on my experiences throughout the assignment. Additionally, coming from a journalism background and a lengthy career in marketing communications, I realise that interviews in both fields focus on informing targeted audiences or seeking insights for commercial purposes, whereas the objectives of academic research interviews are more varied and broader in scope.

Developing questions

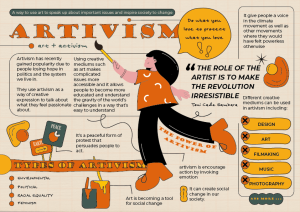

After reviewing the recommended chapters from The Active Interview, I decided to shape the interview around Digital Artivism. I have always been interested in how art and advocacy come together, so I created the following three open-ended questions:

- What picture comes to mind when you think about art and activism?

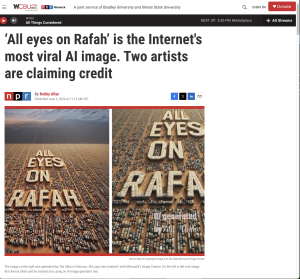

- Is there any artwork or artist that pops up when you think of a strong and impactful visual for the social cause?

- What would be your motivation to get involved in a movement – join a protest or campaign for something?

As suggested in the chapter “Rethinking Interview Procedures” (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995, p. 77), the questions serve as a guide that I would introduce only when the timing feels right. I also reviewed the key points from the handout “Strategies for Qualitative Interviews” and tested the questions with a few people in my close circle to ensure they were easy to understand. In marketing research, there’s a saying that if ‘grandma’ gets the idea, then we’re all set. This principle equally applies in an academic setting and is a key aspect of being “a successful interviewer”.

Furthermore, without mentioning digital as a medium, I left it open to see if my respondents would naturally connect to the subject and how the narratives may shift from there. I also wanted to discuss digital artivism, but I kept it as an improvisational element in the conversation.

The Search for the Random Interlocutors

“Active Interviewing capitalizes on the ways that respondents both develop and use horizons to establish and organise subjective meanings” (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995, p. 57). This led me to consider how cultural and linguistic backgrounds shaped individuals’ interpretations of Digital Artivism. I explored conducting the interviews in two different languages: one in English and the other in Mandarin, which is my mother tongue. I preferred to locate someone who uses English as a second language.

My first respondent was introduced to me by my daughter, who started a local youth initiative during her university years to create social activities and promote engagement for young people aged 16 to 29 in our city, which otherwise lacks relevant opportunities. My respondent is her co-partner and, as I understand, has always been interested in visual arts and speaks fluent English as a second language. We have met a few times before but I am mostly known as the mother of his friend. We agreed to interview in person.

For the second respondent, I created a “wanted” post in a private Facebook group with over 3,500 members, administered by a Taiwanese individual residing in Sweden. Within 24 hours, I received five applications. Without knowing any of the applicants, I selected one who offered to be interviewed through Zoom at the earliest opportunity.

Image of my “wanted” post:

It is translated to:

Hello everyone! I am currently studying for a master’s degree at Malmö University in Sweden. I need to complete an assignment. I need a volunteer to conduct a Zoom interview for about half an hour, and it will be conducted in Mandarin. Your personal information will never be published. Since family or friends are not allowed to participate, I’m hoping to find someone in this group who is willing to help! If you are interested, please send me a private message! Thank you🙏☺️

One of the commenters inquired about the topic, and after some consideration, I decided not to disclose any details about my interview questions. I wanted the interviews to remain fresh and unprepared for the interviewees. I responded by stating that I would write a report on my experience conducting the interviews using academic research methods. I am unsure whether my daughter provided the first respondent with more details about the interview, come to think of it.

Two Settings in Two Languages

In Person with AK

I met AK, my first respondent, at our local library while he took a break from a Halloween activity organised by the youth group at the same location. I assured him that the interview would take no more than 30 minutes. I felt that having a clear timeline would help him feel less stressed and more relaxed, allowing him to focus on our session amid his duties at the event.

After a light-hearted conversation about the ongoing pumpkin carving at the Halloween activity, as well as AK’s current studies in media and his interest in visual arts, I sensed it was the right moment to begin the actual interview. I asked for permission to voice-record our session, and he gave me the green light.

The list of cons from the handout “Strategies for Qualitative Interviews,” states that recording and transcribing interviews can introduce a different dynamic into the social encounter (n.d.). This was true in my earlier experiences back a couple of decades ago when an actual recorder was present. However, I noticed that using a phone to record the interview made both the respondent and me forget about it after a while. Perhaps we had simply grown accustomed to seeing the phone lying on the table. It wasn’t until I was leaving that I realised the voice recording was still on.

In this interview, English was the operating language, and for both of us, it was a second language. I would describe the entire session felt casual. It was certainly a “give-and-take” around topics (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995, p. 76), and I found that the respondent felt comfortable and elaborated more during this interaction. The rapport was great and it could have easily gone over time. Being mindful of this, I made an effort to balance the conversation focused on my topic but also allowing flexibility to explore his narratives. Additionally, having paper and a pen was helpful, as visually oriented individuals often find it easier to express their ideas through drawing rather than finding the right words.

Zoom Call with AC

The Zoom call was scheduled for 10 PM. AC suggested this later evening session since she would be home by around 9 PM and was concerned about my assignment deadline. She was eager to help me complete it as soon as possible. I was impressed by her enthusiasm and didn’t want to dampen her passion. Although this is usually my wind-down hour, I confirmed the schedule. I also learned a valuable lesson from this experience, which I will note down later.

Our initial correspondence took place via Facebook Messenger. Once the time was confirmed, I shared a Zoom link. At the agreed time, we connected, but there was a slight disturbance in our connection that distracted us during our first contact. I felt awkward asking her to quiet down another person who was talking loudly in her space. I also made the incorrect assumption that her mother tongue was Mandarin. Although her Mandarin was quite proficient, she was not a native speaker, even though she highlighted her frequent engagements with Mandarin speakers from Taiwan.

Although I had prepared my questions in Mandarin, some of the phrases I used may not have reflected current common usage because I had been living abroad for several years. This led my respondent to seek further clarification and suggest terms that I realised were more suitable. I also decided not to rely on English for support, even though we did use it very sparingly.

Since much of the information required active interpretation, we both adopted a collaborative approach to constructing the interview. This is generally considered a big no-no in marketing research where it is crucial to communicate precisely to ensure that target audiences receive the right message and that there is no misalignment from a branding perspective. However, the collaborative approach fits well within the principles of active interviewing in a research context which focuses on mutual understanding and co-construction of meaning(Holstein & Gubrium, 1995, p. 57). Moreover, it is not just about giving the right message but about getting the message right.

AC was a gracious and patient respondent, and recording the meeting was not an issue. We developed a fascinating conversation, particularly since she is a master’s student deeply concerned with issues of injustice and de-colonialism. I realised there were additional narratives I could have explored if it had not been past my bedtime and my fatigue had not been so apparent. “You look tired,” AC pointed out, It brought me some embarrassment, especially since I was the one requesting her assistance for this assignment. This certainly highlighted the importance of scheduling interviews at an appropriate time – a valuable lesson I have learned.

“Schedule needs sufficient flexibility to be substantively built up and altered the course of the interview.” (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995, pp. 54-55)

Conclusion

Perhaps it’s a sign of the times: Zoom meetings seem to be much more convenient than in-person meetings. They are also easier to set up. Within 48 hours of my initial Facebook post, the second interview was completed, which was more efficient than I had expected. It was not challenging to build rapport in either setting. Regarding the languages used in the interviews, speaking Mandarin facilitated a deeper connection to the conversation than English.

Additionally, the Mandarin language reflects various contexts in art and activism, prompting different emotional responses. The process of coding and conveying these ideas in both Mandarin and English is an engaging challenge but not an obstacle. Moreover, the interaction allows both respondents to reveal their unique insights and interpretations (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995, p. 58).

The lecture and text on interview techniques offered me new perspectives I had not previously considered, and this exercise has deepened my understanding of the dynamics and meanings involved in research-based interviews, which I find truly empowering. While writing the reflection on my experiences and learning with this post, I plan to adopt a habit of reflective practice in my future work. I see the benefit of approaching my interviews as being an ‘ethnographer of the interview,’ and paying close attention to the interactions during the conversations, as well as the dialogues as was discussed in The Active Interview (Holstein & Gubrium, 1995, p. 74).

Additionally, I have gained insights from the interviews on digital artivism that I will apply to my next blog post assignment. So stay tuned!

References:

- Holstein, J. A., & Gubrium, J. F. (1995). The active interview. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452231640

- Strategies for Qualitative Interviews(n.d.). Interview_strategies.pdf