Image Source: Follow the link to download the book.

Banksy and Activism

Mention art and activism, and Banksy’s name is bound to come up at the top of the conversation. In my view, the Walled Off Hotel in Bethlehem stands out as his most astonishing piece of artivism. Known for having “the worst view in the world,” the hotel opened in March 2017 as a temporary exhibition but continues to operate on the West Bank of Bethlehem(Banksy’s Art in West Bank Hotel With World’s “worst View” | AP News, 2017). This project exemplifies inter-subjectivity by redefining the concepts of ‘place’ and ‘space,’ as outlined by de Certeau (1984, pp. 117-118). The hotel’s physical location represents a ‘place’ with stable material conditions and specific uses. However, Banksy’s art installations transform this ‘place’ into a ‘space’ shaped by the interactions and movements of visitors.

A View from the Walled Off Hotel

The hotel’s installations turn the static ‘place’ into an ‘anthropological space’ where historical and social dynamics are continually reinterpreted. This encourages visitors to interact with the dynamic engagement related to the Israeli-Palestinian conflict. As Turner (2004) discusses in “Palimpsest or Potential Space? Finding a Vocabulary for Site-Specific Performance,” this layered approach allows for a reinterpretation of history and social commentary. Moreover, this transformation reflects the inter-subjectivity concept and the palimpsest nature of site-specific performance. It creates a vibrant space for ongoing dialogue and interactions between visitors and the local community.

From Street to Screen

I feel a strong connection to fellow creators as an artist. I’m a huge fan of Banksy—whether it’s visiting his exhibition at the Moco Museum in Amsterdam or mural hunting in London. While Banksy’s street art may originate in physical locations, he has engaged in the digital landscape effectively through his online presence. I am just one of over 13 million followers on his sparsely updated Instagram account. Each post featuring his murals or special projects instantly receives thousands of comments in various languages, including Japanese, English, and Russian. Most of these posts have gained over a million likes, and have been reposted and shared tens of thousands of times across various platforms (The Power of Banksy’s Art and Activism, 2021).

To explore this, I will first look into how Banksy’s art connects with digital activism, which refers to employing digital tools and platforms to promote social change, and how social media helps spread his creative expression.

Noora, one of our group writers, highlighted relevant insights from Mutsvairo’s “Digital Activism in the Social Media Era” (2016) in her first post, emphasising that the effectiveness of online activism relies heavily on coordination with offline efforts(Noora, 2024). Banksy demonstrates this balance by using digital platforms to amplify his messages while ensuring that his street art continues to make a tangible impact in the offline world.

Photo by Nicolas J Leclercq on Unsplash

Satire and Representation

Banksy’s art is centred around satirical commentary on societal issues. As explained by Stuart Hall that meaning is not inherent in objects, people, or events; rather, it is constructed through cultural and societal contexts. In “The Work of Representation,“ Hall (1997) argues that meaning is created through language, signs, and images that people within a culture use to make sense of the world. This perspective offers me a different view of Banksy’s striking visuals, which are meant to tackle complex social issues and challenge viewers to confront uncomfortable truths. While his work challenges viewers to confront uncomfortable truths, it also raises questions about representation and agency.

My professor, Tobias Denskus, in his blog Aidnography, also reflects on the importance of engaging audiences and stakeholders in the Global North in development discussions. He uses the example of Angelina Jolie’s visit to Chad, documented in her piece for Time, and contrasts it with MrBeast’s loud, cash-in-hand videos. This raises questions about the intended audience and the impact these communications have on humanitarian efforts. One cannot help but agree with Denskus’s reflection: “…but who is the audience and how does it help…?” This also reminded me of Rhodri Davies’ article, “Good Intent, or Just Good Content? Assessing MrBeast’s Philanthropy,” where he notes, “If MrBeast wasn’t making videos about giving, what would he be doing instead?”

I wonder are we, Banksy’s fans, truly empowered by his work, or are they simply being used as emotional sensations?

The Commodity Paradox

This leads to an obvious irony in Banksy’s work. While he critiques capitalism and the commodification of art, his creations have become highly sought-after items rather than accessible forms of expression for the public. During another assignment for this blog to explore interview techniques, an anonymous student shared their enthusiasm for viewing Banksy’s artwork in person, highlighting that the cost of admission to the Moco Museum in Amsterdam, which is €21.95, poses a significant barrier for students. In some extreme cases, people have even vandalised walls and public property to acquire a piece of Banksy’s art(Simpson, 2022). The excitement surrounding his art on digital platforms has helped market his work to the masses, inflating prices and encouraging other street artists to pursue the “Banksy effect” (The Banksy Effect – a Look at Banksy’s Impact on Society & How He Legitimised Street Art, n.d.)

Additionally, Banksy’s decision to remain anonymous adds to his mystique. Viral videos attempting to reveal his identity create such a buzz that draws even more attention to his art and raises questions about the role of identity in activism. As a result, his art has become part of the very consumer culture he seeks to criticise. My brain is spinning with questions: What does this mean for the future of art as a tool for genuine social change? When artivists’ work becomes commercialised, what happens to their original message and intent? Does commercial success change the true meaning of their art, or help spread it? How do digital platforms affect this process? I could go on and on.

Commercialisation and Community Impact

Consider Banksy’s famous shredded piece, Girl with Balloon. The act of shredding it during an auction was intended as a critique of the art market, yet the artwork’s value unexpectedly skyrocketed, and the partially destroyed piece ultimately sold for £18.5 million(Badshah, 2021). This sale further underscores the growing demand for Banksy’s work. In the wake of these events, public reactions have ranged from outrage to admiration, igniting discussions about the value of art and its role in society.

Moreover, there have been instances where Banksy’s art has led to concerns about rising rents. For example, this March when Banksy created a mural on a block of flats in Finsbury Park, London, residents feared their rents would skyrocket due to the increased property value (Skinner, 2024). The building owner reassured tenants he wouldn’t raise the rent, but did mention the possibility of selling the property to Banksy enthusiasts willing to pay a premium. This situation highlights the unintended economic impact of his art on local communities.

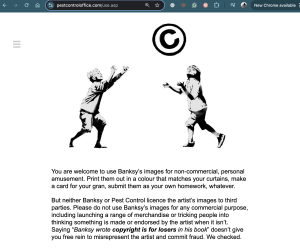

Finally, while Banksy has occasionally sold his art on the streets over the years, unauthorised reproductions frequently appear on platforms like eBay and Etsy. His official website, managed by the Pest Control Office, warns against the commercial use of his images.

The screenshot from the Pest Control Office website regarding the Use of Images.

Despite this, some individuals have been arrested for selling fake Banksy art. This rise in popularity risks shifting his work from a form of activism to a trendy aesthetic, lifting him to celebrity status. As his fame grows, the way audiences interpret Banksy’s work can vary greatly, largely influenced by the art market, digital hype, and his mysterious identity. This complexity leaves me pondering the dynamics at play.

Viral and Value

Thanks to digital media, Banksy’s artwork has become a highly sought-after commodity, often fetching astonishing prices at auction. Social media allows his work to reach a global audience, generating excitement that drives collectors and celebrities into fierce bidding wars. This increased visibility creates a sense of urgency around his pieces, while the limited editions he produces add an air of exclusivity that further inflates their market value. Exhibitions like Dismaland, the Walled Off Hotel, and the ongoing pop-up showcases of The Art of Banksy consistently break visitor records, highlighting the public’s eagerness to experience his art in person. This paradox underscores the complexity of Banksy’s work: while it critiques consumerism and capitalism, it simultaneously becomes an asset within the very system he challenges.

Your Thoughts?

I find myself split between the tension of art as a commodity and art as a form of resistance. The relationship between art, representation, and activism raises important questions about the responsibilities of artists in our digital age. Given this context, which piece of Banksy’s art, aside from raising awareness, has inspired or motivated individuals and groups to take concrete actions in response to the social and political issues he highlights? I’d love to know!

References

Badshah, N. (2021, October 14). Banksy sets auction record with £18.5m sale of shredded painting. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2021/oct/14/banksy-auction-record-shredded-painting-love-is-in-the-bin

Banksy. (n.d.). https://banksy.co.uk/licensing.html

Banksy’s art in West Bank hotel with world’s “worst view” | AP News. (2017, March 3). AP News. https://apnews.com/article/b19763edb0a44037adb0cafcc3e0b223

Banksy Explained. (2023, August 18). Home – Banksy explained. Banksy Explained -. https://banksyexplained.com/

Blanché, U. (Ed.). (2023). Banksy – The Early Shows. 1997-2005. https://books.ub.uni-heidelberg.de/arthistoricum/catalog/view/1201/2062/108482

Certeau, M. de. (1984). The practice of everyday life (S. Rendall, Trans.). University of California Press. https://chisineu.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/10/certeau-michel-de-the-practice-of-everyday-life.pdf

Denskus, T. (2024, October 6). What if MrBeast really is one of the futures of philanthropy—and what does that mean for communicating development? Aidnography. Retrieved from https://aidnography.blogspot.com/2024/10/mrbeast-givedirectly-future-philanthropy-communicating-development-aid.html

Davies, R. (n.d.). Good intent, or just good content? Assessing MrBeast’s philanthropy. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/full/10.1002/nvsm.1858

Hall, S. (1997). The work of representation. In Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices (pp. 15-30). Sage Publications.

Mutsvairo, B. (2016). Digital activism in the social media era. Palgrave Macmillan.

Noora. (2024, November 5). Protests online and offline – IDA. IDA. https://wpmu.mau.se/msm24group4/2024/10/21/protests-online-and-offline/

Simpson, D. (2022, October 19). Crowds, vandals, chaos: what happens when Banksy sprays your wall? The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jan/16/help-ive-been-banksied-how-we-coped-with-banksy-street-art-fame

Skinner, T. (2024, March 20). Owner of Banksy mural flats says he won’t put up rent – but could be tempted to sell. NME. https://www.nme.com/news/music/owner-of-banksy-mural-flats-says-he-wont-to-put-up-rent-but-could-be-tempted-to-sell-3603281

The Banksy Effect – A look at Banksy’s impact on society & how he legitimised street art. (n.d.). Maddox Gallery. https://maddoxgallery.com/news/97-the-banksy-effect-how-banksy-legitimised-street-art/

The power of Banksy’s art and activism. (2021, May 7). Sothebys.com. https://www.sothebys.com/en/articles/the-power-of-banksys-art-and-activism

Turner, C. (2004). Palimpsest or potential space? Finding a vocabulary for site-specific performance. In Theatre and Performance Design (pp. 77-89).