Every 10 minutes, a woman is killed. Violence against women and girls remains one of the most widespread human rights violations, impacting half of the global population. No country is safe, although in some places, “it is more dangerous to be a woman than a soldier”, as NATO Colonel Dr. J.A. Olsen noted in an interview with me back in 2012.

On this International Day to End Violence against Women, we emphasise the vital role of data activists in combating feminicides and addressing biases in AI-statistics.

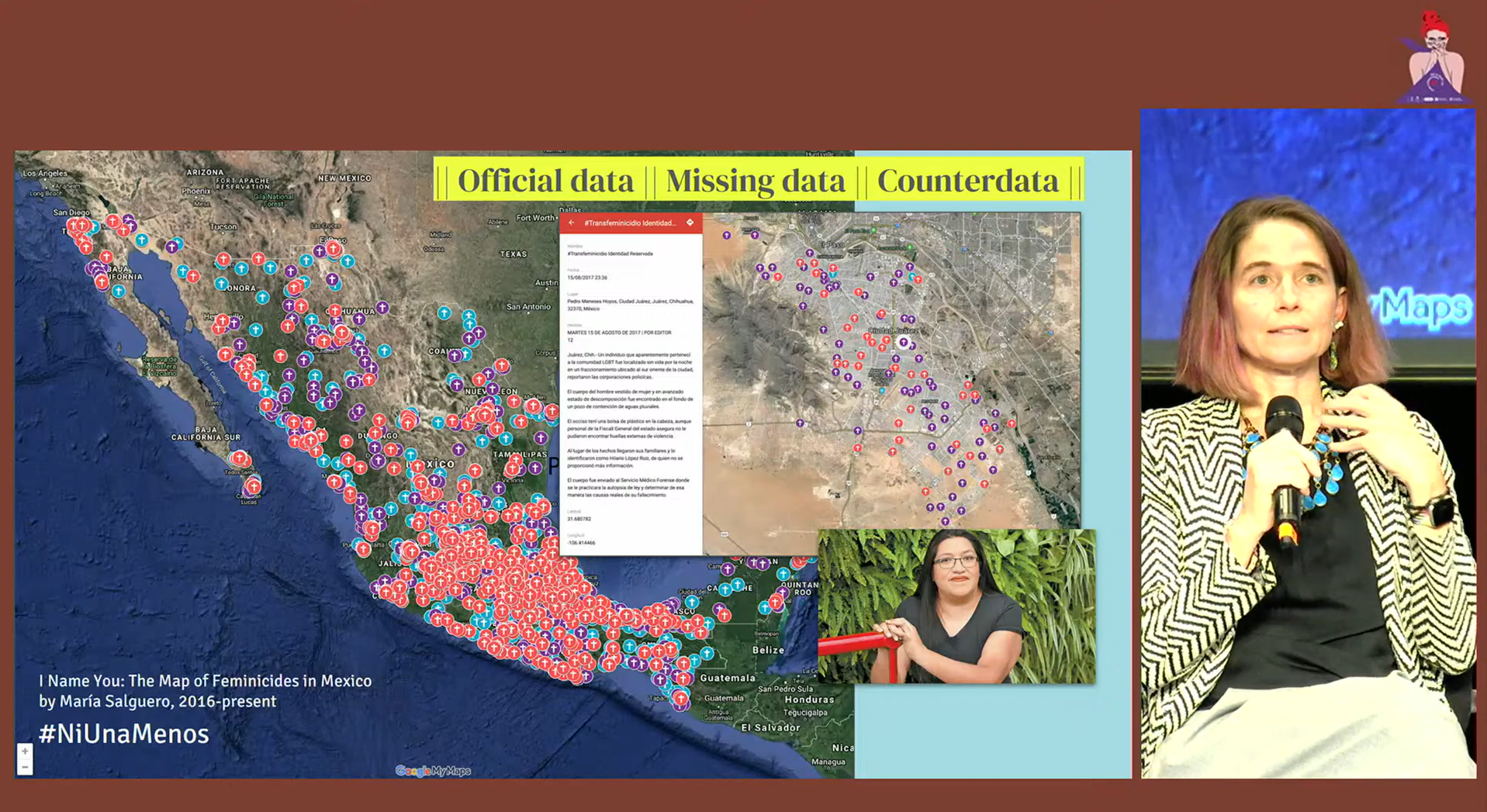

As the world becomes increasingly data-driven, collecting data on systemic violence emerges as a new and powerful form of feminist activism. The 20th Forum against Gender-Based Violence, recently held in Barcelona, brought together renowned experts on data activism from Europe and Latin America. Today, there are over 190 feminicide data activism projects worldwide. Many of these initiatives were launched by individuals or small groups of women in the wake of the 2015 Ni Una Menos (“Not One [Woman] Less”) movement. Ranging from gathering news clippings to building comprehensive databases on feminicides, these projects share a common goal: challenging official statistics and working to end violence.

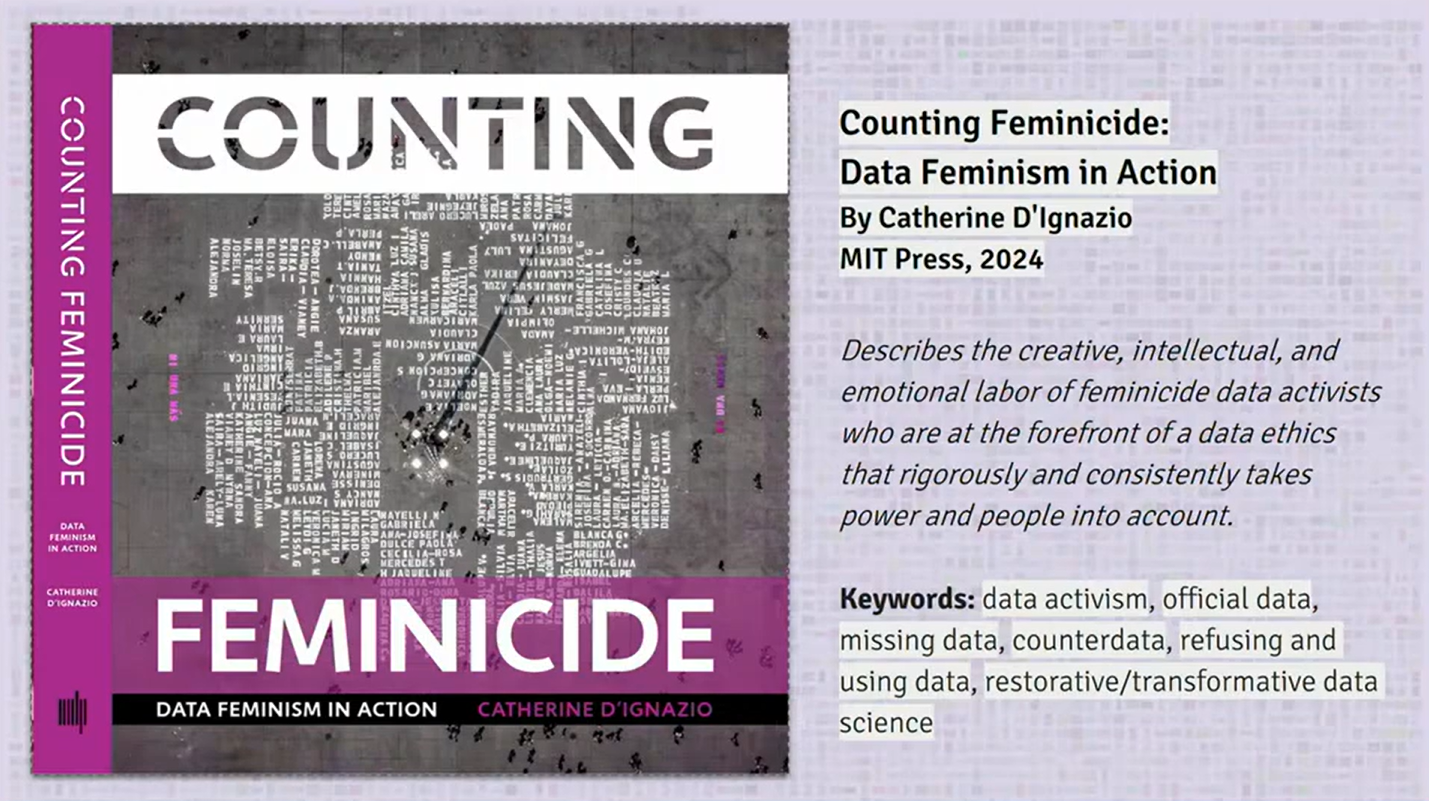

“Feminicide data activism points us toward a restorative and transformative data science, that is using data to heal, and to restore the rights and the dignity of communities. This approach fundamentally differs from the data science that we teach in institutions such as MIT, where I work”, explained Catherine D’Ignazio, professor and director of the Data + Feminism Lab at Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), during the event.

Data science reinforces hegemony rather than dismantling it, according to D’Ignazio. “AI is accelerating the biases of a racist, sexist, and transphobic world. We want to challenge the narrative of the benefits of AI”, added.

When it comes to feminicides, two fundamental issues stand out: naming violence is essential to acknowledge it, while counting acts of violence is crucial to addressing it.

Herein lies the problem: many countries, including those in Europe and North America, lack a legal definition of feminicide (or femicide). “In the EU, countries like Germany strongly opposed the use of femicide because it sounded too close to genocide”, said Marceline Naudi, former coordinator at European Observatory on Femicide.

Global legal progress in the area has been led by Latin American countries, with Costa Rica (2007), Guatemala (2008) and Chile (2010) among the first countries to enact such laws. This situation perpetuates the misconception that violence against women and girls mainly occurs in the Global South.

On the other hand, gathering (or not gathering) data proves to be inherently a political act, perpetuating the erasure, misrepresentation and neglect of communities. “How is it possible that, in the age of technology, we have such basic data about feminicides? It is shameful. The lack of official data constitutes institutional violence”, warned Graciela Atencio, journalist and founder of the Spanish observatory Feminicidio.net. She emphasised: “With limited resources, we have collected data on over 60,000 feminicides since 2010. How come that we have more data than the states? The rise of the far-right and the denial of gender-based violence threaten to roll back progress on data collection”.

In contexts of conflict and war, violence against women is widely spread and more often underreported. “Colombia recorded 616 cases of feminicide in 2022, of which 161 were linked to narco mafias and 104 to hitmen. Feminicides increase in places with high militarisation, where armed men serve legal or illegal armies, and narcotrafficking operations”, concluded Carol Rojas, Director of the Colombian Observatory on Feminicides.

AI and data colonialism

D’Ignazio recalls the urgent need to decolonialise data science and AI. These are three key ideas shared by her during the forum, as well as in her latest book, Counting Feminicide:

- Areas such as education, health and housing are characterised by different forms of structural inequality, violence and trauma based on patriarchy, white supremacy, classism, colonialism, and more. Using data science and AI automated systems to allocate resources or social services may exacerbate harm, if data are not confronted. This has been coined as data terrorism.

- Data are compared to land, air, water as free resources to be mined, extracted, privatised, and profited from. Algorithmic automation and lack of consent leads to processes of dehumanisation, reducing individuals to mere commodiable metrics. This is known as data colonialism, which works at the service of surveillance capitalism.

- Computer science occupations are mostly dominated by men. In opposition, data activism is largely led by women and gender nonconforming people. Their research is often unwaged work. This is consistent with the feminist concept of social reproduction: the care work that sustains, maintains, and reproduces society remains devalued, and is mostly carried out by women.

Humanising data

Data activists such as Graciela Atencio or Carol Rojas gather three to four times more data than official statistics. However, their ultimate goal is to humanise these victims, honour them and, as Atencio said, “work for the collective memory”. Powerful examples include Say Her Name, a movement raising awareness of Black women victims of police brutality in the US, and Zapatos Rojos (“Red Shoes”), an art installation by Mexican artist Elina Chauvet that has been replicated worldwide.

For many of these activists, humanising data also means rejecting fully automated processes to collect data on feminicides. Instead, they review cases one by one as an act of mourning and remembrance. This involves navigating the press and social media, regularly encountering victim-blaming news, and enduring the significant toll it takes on their mental health.

Numbers are key in policy-making. However, undeniable tensions exist between leveraging technology and adopting more handcrafted approaches, as well as between using numbers to illustrate the magnitude of the violence and avoiding the reduction of victims to mere statistics. Could we say that feminicide activists are continually fighting against epistemic violence — described by Gayatri Spivak — embedded in numbers?

Today we urge you to take note of the UN (official) figures and support your closest data activist group or start your own to end this pandemic of violence.

!["Ni Una Menos" (“Not One [Woman] Less”) movement is a grassroots feminist movement, which started in Argentina in 2015 to campaign against gender-based violence.](https://wpmu.mau.se/msm24group5/wp-content/uploads/sites/100/2024/11/niunamenos3.jpg)

Further reading

D’IGNAZIO, Catherine, KLEIN, Laura F. (2020) Data Feminism. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11805.001.0001

D’IGNAZIO, Catherine (2024) Counting Feminicide: Data Feminism in Action. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/14671.001.0001

MHLAMBI, Sabelo, et al (no date) AI Decolonial Manyfesto. https://manyfesto.ai/

MHLAMBI, Sabelo, TIRIBELLO, Simona (2023) “Decolonizing AI Ethics: Relational Autonomy as a Means to Counter AI Harms”. Topoi 42, 867–880. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-022-09874-2

RICAURTE, Paola, et al (no date) Tierra Común: Intervenciones para descolonizar los datos. https://www.tierracomun.net

WARD, Jeanne, et al (2023) “Gender-Based Violence and Artificial Intelligence (AI): Opportunities and Risks for Women and Girls in Humanitarian Settings”. London: Social Development Direct. https://sddirect.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-10/GBV%20AoR%20HD%202023%20GBV%20and%20AI%20final%20.pdf