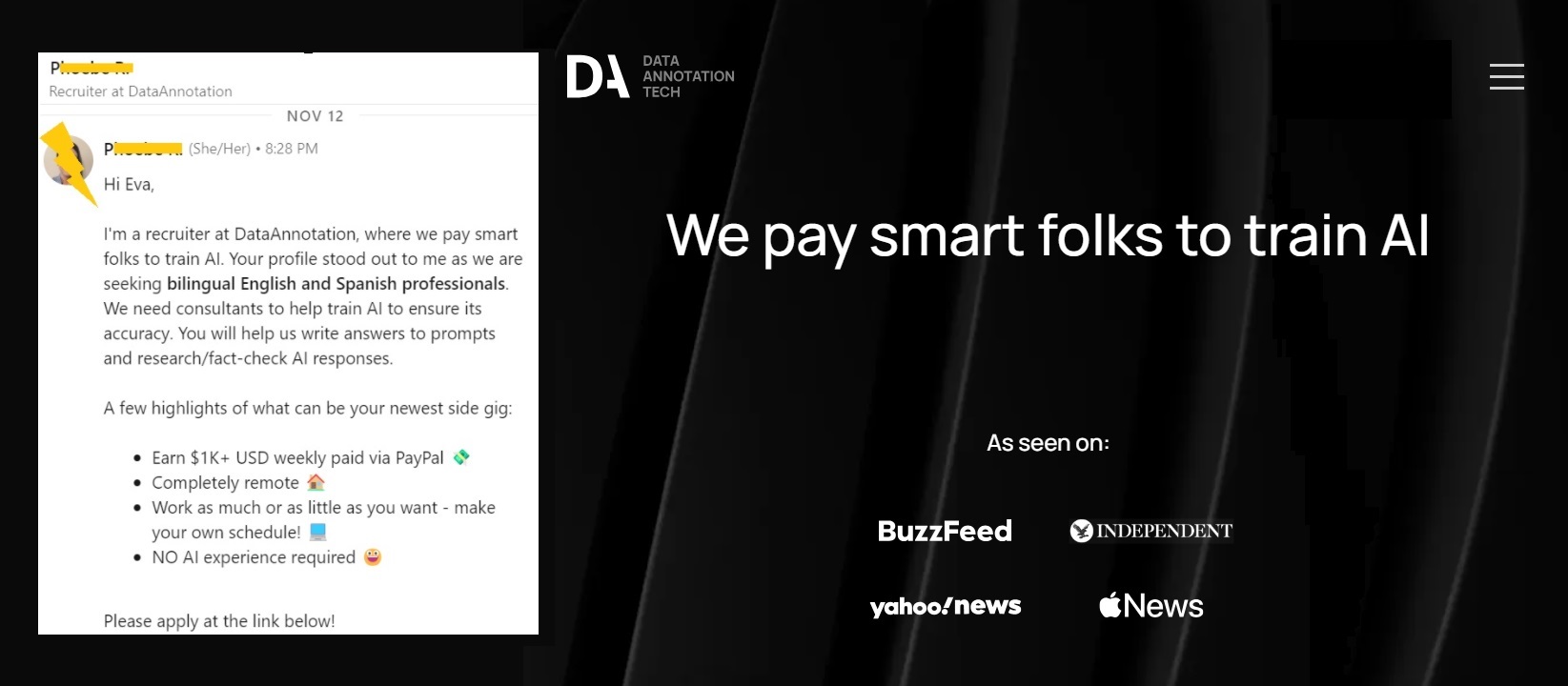

A mysterious job offer popped up in my Linkedin inbox about a month ago: “Hi Eva, I’m a recruiter at DataAnnotation, where we pay smart folks to train AI. Earn $1K+ USD weekly paid via PayPal. Work as much or as little as you want — make your own schedule!” (see the full message below). After weeks of intensively researching gig workers and labour conditions for this blog, the forces of AI seemed to be pulling me in.

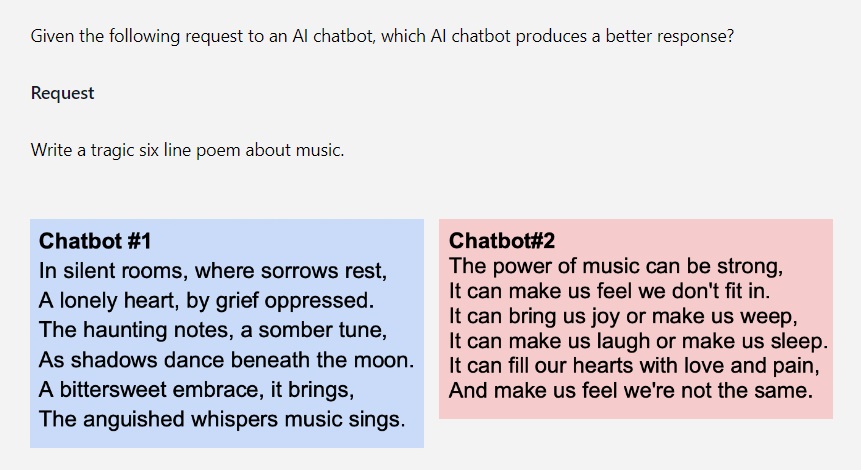

Following the recruiter’s advice and a genuine interest in fieldwork, I applied for the offer and immediately received a one-hour test. The assessment was a prerequisite to access paid projects, including: “AI chatbot training, text classification (sentiment analysis), content moderation, image classification, search evaluation, creative writing, data entry, and more”.

Fact-checking, language skills, analytic techniques, critical thinking and creativity were some of the areas evaluated. However, a disclaimer stated: “All responses must be written by you from scratch. We are not looking for perfect English — it’s fine if there are typos or grammar mistakes. Do not use any translation tools to assist you”. In other words, was AI banning me from using AI itself in order to prove my humanity?

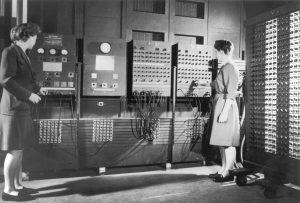

What seemed surprising — and even incoherent — reveals one of the most fundamental premises of this technology: AI is neither artificial nor intelligent, and requires large amounts of human labour. However, the workforce needed to run AI systems remains deliberately hidden as “ghost work” (Gray and Suri, 2019).

“All technologies — even the most seemingly advanced, autonomous, artificial intelligence systems — are ultimately products of people”, states Jathan Sadowski, Senior Lecturer at Monash University (Australia), on his website. The efforts to hide the role of human labour is described by the author as the “Potemkin AI”, a façade of cultural hype made to attract venture capital. “AI systems are, in large part, technical illusions to fool the public (…) AI systems deploy technical buzzwords that sound like a magician’s incantations: Smart! Intelligent! Automated! Cognitive computing! Deep learning! (…) If an AI application relies heavily on human labour rather than machine learning, that doesn’t make for a good sales pitch to venture capitalists and customers”, explains (Sadowski, 2022).

AI winter in 2025?

While tech moguls such as Elon Musk announced that AI will surpass human intelligence by 2025, the AI hype grows exponentially as do the chances of falling into a new AI winter. AI companies’ revenues have skyrocketed over the past two years, but their computational costs for running more sophisticated AI models have also multiplied. For example, improving an AI’s recognition accuracy from 60% to 67.5% required quadrupling the training data, and some top tech corporations, including OpenAI, are currently operating at a loss. The fear of a looming AI winter freezing all funding and interest in AI — as already happened in the 1970s — is real.

In the meantime, we are also witnessing the emergence of a planetary and fragmented labour market for gig work (Graham, 2022) to fulfill the urgent need for “humans in the loop” to retrain AI (Schmidt, 2022). Contrary to the fundamental economic law of supply and demand, the current high demand for human power translates into a race to the bottom in terms of wages and labour rights, and a “proletarianisation” of data science jobs (Steinhoff, 2022).

Technocolonialism in the gig economy

India and the Philippines have become the main market for content moderation outsourcing, but Indian and Filipino content cleaners were left out of the $52 million legal settlement to provide relief to Facebook content moderators exposed to distressing and violent content. Venezuela has become the source of cheap and highly qualified labour in the field of data annotation due to the socioeconomic collapse of the country, aggravated by hyperinflation and mass starvation after 2017 (Schmidt, 2022). Other examples of the emergence of modern slavery across the globe have been described by my colleague Pree in this blog post.

Thus, the AI industry profits from catastrophe, and its dynamics of data capital and digital labour follow the colonial political and economic relations where the margins serve the core (Graham, 2019). In other words, tech companies exacerbate AI colonialism or technocolonialism (Madianou, 2024).

The AI industry race is dominated by the United States and China, redefining the geographies of the core and the periphery of this neocolonial extractivism. The fact that many citizens in the Global North also earn precarious wages through piecemeal digital work — producing datasets, training AI systems, serving platforms — reveals how the periphery is also nestled unevenly inside the imperial core of innovation (Sadowski, 2022).

Data annotators wanted

As I wait to hear back from my potential employer, I navigated Linkedin to search for current DataAnnotation employees in my area (Spain). These are some of my findings:

- 17 profiles are currently identified as “AI data trainer”, “data annotator”, or “AI content writer” for DataAnnotation in Spain (the global workforce is estimated to be between 5,000 and 10,000 employees worldwide, according to the company on Linkedin).

- 100% of them have been hired in the past nine months.

- 100% of them have higher education qualifications: BA (a total of 6 employees), MA (9), and PhD (2).

- Their educational backgrounds vary across the following fields: Language, Literature and Translation (6 employees); Communication (3); Education (3), and other disciplines (5).

- 100% of them have an advanced or proficient level of English.

- 47% of them have between 5 and 10 years of work experience, followed by 24% with more than 20 years of work experience.

- 53% of all profiles displayed the “Open to work” frame in their picture.

- 70% of them are women.

To sum up, the average profile of a Spanish AI data trainer for DataAnnotation is: a woman with an MA in Languages or Communication, and between 5 and 10 years of relevant work experience. In other words, me.

However, what I found particularly striking is that half of the Spanish AI trainers at DataAnnotation have publicly indicated that they are seeking alternative employment opportunities, despite having started this role less than a year ago and being assured of earning over $1,000 USD per week. How come the allegedly $4,000 monthly income is not enough to keep Spanish workers in the loop when the average monthly salary in Spain is €1,500 net?

AI and care

The price for annotations depends on the complexity and the level of accuracy of the task, starting from $0.05 for a box (Graham, 2022). An individual human would need up to two hours to process a complex segmentation of an entire image, with 99% of accuracy, which costs $6.40 retail. Tech companies would not be profitable if they paid their workers the minimum wage at the standard of Western nations. Thus, the tasks flow to the planetary workers willing to accept the lowest remuneration possible (Schmidt, 2022).

DataAnnotation is no exception. On this Reddit thread, employees share their experience on being paid $25 per hour for high-quality labeling — such as, legal classification, driverless car data, or medical imagery — or only $35 in three months. Some regular employees have also shared their huge downturn in projects during the last months. “I haven’t had anything to work on, except for the OG imaging projects which are paid $0.03 a pop, and I’m making $20 maximum”, explains a data annotator.

I continued exploring the DataAnnotation’s website, which is exclusively designed for employee branding and recruitment. There is a curated effort to make the position attractive by highlighting a section of testimonials — some of them with real people, others which appear to be generated by AI. This is an example that caught my attention:

“Daycare”, “postpartum” or “post-maternity” were words I certainly did not expect to find on a DataAnnotation recruiter video. While the job offer is presented as an opportunity to balance work and life, the company is focusing its efforts to hire a specific niche: qualified workers and mothers willing to accept a lower pay in order to be able to work from home.

Training and raising AI, cleaning digital content, and managing sentiment analysis are the equivalent of the care work that has been traditionally carried out by women — caring and raising children, cleaning, cooking, etc. In the feminist concept of social reproduction, care is everything humans do to maintain, continue, and repair the world. Care is often invisibilised but essential to sustain human life, as is the “ghost” data labour that nurtures AI. Thus, behind the wonders of the corporate motto of “freedom and flexibility”, tech companies devalue vital data work by perpetuating an extractivist neocolonial logic, but also the powers of techno patriarchy.

Images: Cogito Tech (feature), DataAnnotation.tech, Linkedin, ARL Technical Library and DataAnnotation youtube.

References

BLOCK, Hans, RIESEWIECK, Moritz (2018). The Cleaners. https://vimeo.com/ondemand/thecleaners2018

DataAnnotation (2024). https://www.dataannotation.tech/

DataAnnotationTech (2024). “Parent Testimonial Video”. Youtube. March 25. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UZONSTlpCCM

DataAnnotation Linkedin (2024). https://www.linkedin.com/company/dataannotationtech

D’IGNAZIO, Catherine, KLEIN, Laura F. (2020) Data Feminism. The MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/11805.001.0001

ELLIOT, Vittoria; PARMAR, Tekendra (2020). “The despair and darkness of people will get to you”. Rest of the World. July 22. https://restofworld.org/2020/facebook-international-content-moderators/

GALINDO SORIANO, Eva (2024). Interview with Joan C. Tronto: “AI solutions don’t subsitute care”. Malmö University: Artificial Inequality (blog). November 29. https://wpmu.mau.se/msm24group5/2024/11/29/tronto-ai-solutions-dont-substitute-care/

GRAHAM, Mark; ANWAR, Mohammad A. (2019). “The Global Gig Economy: Towards a Planetary Labour Market?” First Monday 24 (4), April 1. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v24i4.9913

GRAHAM, Mark; FERRARI, Fabian (eds.) (2022) Digital Work in the Planetary Market. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/13835.001.0001

GRAY, Mary L., & SURI, Siddharth (2019). Ghost work : how to stop Silicon Valley from building a new global underclass. Boston. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

HAMMOND, George (2024). “Elon Musk predicts AI will overtake human intelligence next year”. San Francisco: Financial Times. April 8. https://www.ft.com/content/027b133f-f7e3-459d-95bf-8afd815ae23d

HAO, Karen; HERNÁNDEZ, Andrea P. (2022). “How the AI Industry profits from catastrophe”. Massachusetts: MIT Technology Review. April 20. https://www.technologyreview.com/2022/04/20/1050392/ai-industry-appen-scale-data-labels/

KARIM, Ridoam (2024). “Is an AI winter coming?: Navigating the cycles of AI hype and just regulation”. Malaysia: Monash University. June 25. https://lens.monash.edu/@business-economy/2024/06/25/1386756/is-an-ai-winter-coming-navigating-the-cycles-of-ai-hype-and-just-regulation

La Sexta (2024). Redes Sociales: La Fábrica del Terror. October 14. https://www.lasexta.com/temas/salvados_redes_sociales-1

MA, Jason (2024). “OpenAI sees $5 billion loss in 2024 and soaring sales as big ChatGPT fee hikes planned”. Fortune. September 28. https://fortune.com/2024/09/28/openai-5-billion-loss-2024-revenue-forecasts-fundraising-chapgpt-fee-hikes/

MADIANOU, Mirca (2024). Technocolonialism: When Technology for Good is Harmful. London: Polity Books.

MOROZOV, Evgeny (2023). “The problem with artificial intelligence? It’s neither artificial nor intelligent”. The Guardian. March 30. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/mar/30/artificial-intelligence-chatgpt-human-mind

MULDOON, James; GRAHAM, Mark; CANT, Callum (2024). “Meet Mercy and Anita–the African workers driving the AI revolution, for just over a dollar an hour”. The Guardian. July 6. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/article/2024/jul/06/mercy-anita-african-workers-ai-artificial-intelligence-exploitation-feeding-machine

RAJENDRAN, Preetha (2024). “All is fair in AI Development (?)”. Malmö University: Artificial Inequality (blog). November 20. https://wpmu.mau.se/msm24group5/2024/11/20/all-is-fair-in-ai-development/

Road To Retire (2024). “What Is Going On With DataAnnotation.Tech??”. Youtube. August 24. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x6V2K-1tayY

SADOWSKI, Jathan (2022). “Planetary Potemkin AI: The Humans Hidden inside Mechanical Minds” in GRAHAM, Mark; FERRARI, Fabian (eds.) Digital Work in the Planetary Market. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

SADOWSKI, Jathan (2024). “Home page” (accessed 14/12/2024). https://www.jathansadowski.com/

SCHMIDT, Florian A. (2022). “The Planetary Stacking Order of Multilayered Crowd-AI Systems” in GRAHAM, Mark; FERRARI, Fabian (eds.) Digital Work in the Planetary Market. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

STEINHOFF, James (2022). “The Proletarianization of Data Science” in GRAHAM, Mark; FERRARI, Fabian (eds.) Digital Work in the Planetary Market. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

WFHJobs (2022). Reddit: “Is Data Annotation a scam?”. https://www.reddit.com/r/WFHJobs/comments/135xojm/is_data_annotation_a_scam/?rdt=36572