Introduction: The Many Mediums of Qualitative Interviews

As a development communication student navigating my ongoing semester on research methodologies and strategies, I’ve already read quite a few texts guiding potential researchers in conducting interviews–one of the most popular and overly-relied data collection methods in qualitative research (Silverman, 1998, as cited in Mills, 2014, Ch 3). Despite the painstaking efforts taken by experts to lay standard guidelines about the interviewing process, a lot is experienced first-hand by researchers and their participants that rarely makes its way into the academic literature.

One of the reasons could be that interviewing as a data collection method is a highly subjective process. Writing about biography as a research method, Janet L. Miller notes that ethnographic interviews, specifically face-to-face ones, are “often unpredictable events” shaped not only by the questions asked and answered but also by the thoughts, feelings, and assumptions of the interviewers and their research participants (p. 62).

In addition to personal traits, the researcher’s chosen medium is crucial in determining the interview’s outcome. Scholars argue that the medium of communication –electronic or face-to-face– can restrict or allow access to various types of data. Even though the popularity of electronic interviews (telephone interviews or Zoom calls) has grown over the years, especially since the COVID 19, face-to-face interviews are dominantly preferred by qualitative researchers due to their ability to provide symbolic and non-verbal cues as supplements to verbal information, leading to deeper contextual understanding of the phenomenon under study (Irvine et al., 2012).

In this blog post, I’ll compare a Zoom and face-to-face interview I conducted to see the effectiveness of each as a data collection tool in qualitative research. Through this small comparative study, I aim to understand whether changing the medium of communication impacts researcher-participant interaction and how this understanding will aid my future research work, that is, the upcoming degree project. The purpose of this activity and the post is not to pitch one medium against the other (the experiment is too small to make any concrete generalisations). Instead, drawing from my experiences, I wish to highlight the circumstances under which each medium would work the best.

Making the First Contact: Discoveries and Lessons Learnt

I recruited the interview participants through credible channels—an alum group on WhatsApp and a friend. For the Zoom interview, I posted a request on the WhatsApp group. The participant reached out to me the next day. It was interesting to see that in his message, the participant used the word “chat” instead of “interaction,” which I had purposefully used in the original request to strike a balance between a formal interview and casual talk. The conscious or unconscious use of “chat” shows how participants begin to influence the interview’s course from the pre-interview stage. For example, I switched to a topic-based, unstructured interview to suit a chat-like style of conversation instead of a question-based, semi-structured guide that I had created for a semi-formal “interaction.”

Arranging the face-to-face interview required more pre-interview engagement than the Zoom one. Since I had approached this participant through a common connection, a friend, I assumed that he had narrated my motive for conducting the interview verbatim to the participant as I had to him. Hence, in my first direct message, I requested the participant to share a convenient interview time and place. I realised my error when the participant replied with a message asking for further clarity about the process with questions such as ‘What kind of answers was I expecting?’

Researchers should remember that much information gets lost when initially engaging a middle person as a communication cord. They have no control over what the middle person said or left out while conveying their request. From my first bumpy encounter, I learned that it is crucial to repeat the details to the participants so that they can form a better informed decision despite their initial agreement to participate in the interview.

Another lesson I learned the hard way was that it is crucial to clearly convey deadlines to the participants. I used “ideally” to avoid being too assertive in communicating the deadline to my face-to-face interview participant. I assumed it’d be as easy to arrange as my Zoom interview which took place within three days of posting the original message. However, when the participant texted that she could only meet me on a date after the ideal deadline as she had other engagements, I had to postpone this assignment to the second submission date. Clear communication regarding deadlines and a well-structured research timeline with a window to accommodate last-minute changes are life-saving qualitative research strategies that use interviews and focus groups as a data collection tool.

Real vs.Virtual: Is there a rivalry?

One of my key takeaways from this small exercise was that the medium used to conduct the interview should align with the nature of qualitative research and its objectives. It will be hard to for researchers to get the complex, rich, and insightful data for their research project if they only rely on Zoom for interviewing their participants. More so if their purpose is to conduct exploratory, ethnographic research that, for instance, wants to dig into the complexities of everyday lived realities of a weaving community.

Zoom interviews can be an excellent way to seek information from subject experts or engage with participants on specialised topics. For instance, when asking the participant about his experiences of studying development studies as an Indian student, Zoom allowed for a focused interaction that rarely strayed from the topic under discussion.

Despite my attempts to facilitate a chat-like environment, our conversation heavily relied on a question-answer engagement format using a semi-formal to formal tone. I was glad that the participant had consented to the video feature that allowed me to use non-verbal cues to stimulate, to an extent, a friendly, chat-like atmosphere. On the other hand, my face-to-face interview with the participant about her experiences of living in Japan as a young Indian woman made me realise that face-to-face interviews are crucial when researchers approach the phenomenon under study from a multi-layered perspective.

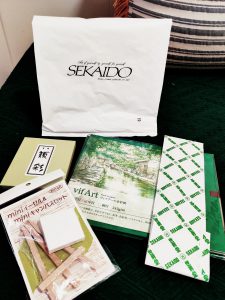

The interview, which was to take place at a ramen shop for around an hour, turned into a four-hour affair covering multiple locations. From the ramen shop, the participant willingly took me to the art shop-cum-studio that she frequently visited to take classes. As we explored the rows of art supplies, the participant delved deeper into her interest in charcoal and still life painting, seeing the process of painting with other learners as a way of seeking companionship and forming ties with a community in a foreign country known for its homogeneous culture. We then made our way to a tea café where the participant, now considerably at ease, talked about the unconventional and contradictory decisions that influenced her decision to settle in Japan. These details starkly contrasted with ones provided by her during the first hour of the meeting at the ramen shop, where the participant mainly talked about the positive influences that motivated her to move to Japan, such as her love of anime.

After my study, I feel that face-to-face interviews do a much better job of helping researchers to uncover more than just the ‘good’ details or ‘happy’ anecdotes of the participant’s experiences by offering a chance to create a friendly rapport. Here, “friendly” does not merely entail being polite and considerate. Rather they offer an opportunity for the researcher to connect with the participant in a genuine and an authentic manner through the commonality of experiences that might not be possible over Zoom calls and telephone interviews.

For instance, the rapport I built with the face-to-face participant allowed us to move back and forth from the question-and-answer style of engagement (dominant when we sat facing each other at the ramen shop) to that of confessions and monologues (during the tour of the art gallery led by the participant with me following and much later as we sat side by side watching the outside world through the café window). The frequent shift in location and our position with respect to one another also led me to open up about my experiences of settling and adjusting in Japan. This allowed me to extend solidarity to her experiences by exchanging stories of cultural shock, language challenges, and changes in attitude and everyday lifestyle. On the contrary, even though I shared a similar educational background with the Zoom participant, the platform offered limited options to participate in collaborative meaning-making (Holstein & Gubrium, 2011).

However, one should remember that face-to-face interviews can be time-consuming, exhausting, and costly. Under circumstances when there are travel restrictions due to natural disasters or conflicts, a video Zoom call definitely is a better substitute. From the point of view of future projects, my small experiment has convinced me to align my data collection strategy with the research purpose in which either medium can be used as per the study objectives and other constraints. That said, I enjoyed my face-to-face interview more than the Zoom one. Even though I am an introvert who finds it difficult to instantly open up and gets easily tired after talking to people for more than an hour– I slept through the entire next day due to exhaustion— yet my small study showed me that face-to-face interviews help build stronger, meaningful connections with the participants and provide more opportunities for them to assert their agency.

References

Holstein, J.A., & Gubrium, J.F. ( 2011). Introduction. In The Active Interview. (pp. 1–6). http://dx.doi.org/10.4135/9781412986120.n1

Irvine, A., Drew, P., & Sainsbury, R. (2012). ‘Am I not answering your questions properly?’ Clarification, adequacy and responsiveness in semi-structured telephone and face-to-face interviews. Qualitative Research, 13(1), 87 –106. http://qrj.sagepub.com/content/13/1/87

Miller, J.M. (2008). Biography. In Lisa M. Givens (ed.), The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, (pp. 61-63). Sage Publications, Inc.

Mills J. (2014). Methodology and Methods. In J. Mills & M. Birks (eds.) Qualitative Methodology: A Practical Guide. Sage Publications Ltd.