Discourse on this blog and elsewhere has referenced international development studies being at a kind of crossroads, or ‘critical moment’ (Telleria, p.15). There are multiple competing directions of potential travel for the teaching and practical application of development studies and research. Decolonisation is also a live issue, with recent literature seeking to “disrupt and renew understandings of development and articulate a more progressive politics” (Biekart, Camfield, Kothari & Melber, 2023)

In considering the future direction of thinking in the field, it is useful to take stock of where the commonalities and fault lines lie in the various approaches. A recent paper by Andy Sumner of King’s College London and current president of the European Association of Development Institutes (EADI), attempts to set the development picture in 2024. Pointing out that Development Studies as an academic discipline now has at least 50 years of history, Sumner expands on the crossroads analogy by proposing a “typology of development studies” in an “indicative rather than absolute” attempt to outline the major schools of thought in development today (Sumner, p.1283). Sumner’s findings propose that a development quadrant may be a more appropriate way of situating priorities and thinking in the sector.

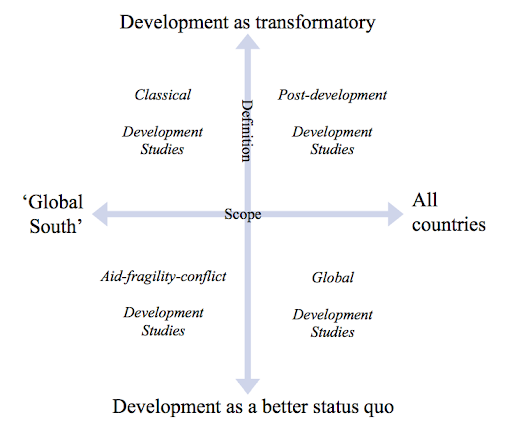

The typology (fig.1) primarily asserts that the main differences in development studies thinking today falls around two main issues. The first is the view that development should have a “transformatory” effect on society, versus a “more modest vision of a better status quo”. The second is the view that development is a global issue, compared with a preference for a focus on the countries of the Global South (ibid). Therefore, post-development thinking, which broadly speaking takes a critical approach to mainstream development as pursued by Western countries, would align with the transformatory/all countries quadrant. On the direct opposite side lies a grouping Sumner identifies as ‘Aid-Fragility-Conflict Development Studies’, which is largely concerned with very poor countries identified as being aid dependent and affected by conflict.

Fig.1: “Schools of thought in Development Studies: a typology.” (Sumner, p. 1285).

Referencing Sumner’s paper on the EADI blog, researcher Caroline Cornier posits that a lack of clarity on the agreed meaning of ‘development’ and consequent ambiguity around its objectives results in “development researchers talking past each other, instead of constructively debating” (Cornier, 2024). Sumner argues that one of the strengths of his typographical approach is that it brings the tangible and existing differences in approaches in development to the fore, allowing for more frank and informed debate and discussion among development practitioners and academics.

Perhaps most significantly in this regard, the distinctions between the top and bottom halves of the diagram point most clearly to differing approaches between transformatory and more moderate forms of development. At an EADI workshop which discussed the paper earlier this year, academics provided varying interesting perspectives on potential aspects of Sumner’s typology. Some of the issues raised in the discussions around the framing and future of development included the “obsession with Gross Domestic Product” as a yardstick of progress, rights-based approaches and the ethical imperatives of decolonising knowledge, underlining the diversity of views in where emphasis should be placed in development studies (Moyeen and Muzaffar, 2024).

In reflecting on the main boundaries within development studies identified in his paper, Sumner also turns to considering the need for “new conceptual thinking and vocabulary” in the field. Sumner suggests that one such approach could involve moving away from the ‘development’ label entirely and instead centering the potentially more unifying concepts of ‘global justice’ or ‘global equality’ (Sumner, p.1294).

Andrea Cornwall, Professor of Global Development & Anthropology at King’s College London, takes this further. For her, decolonial practice in development should not simply be a matter for university programmes. In a contribution to the 2020 book Beyond the Master’s Tools? Decolonizing Knowledge Orders, Research Methods and Teaching, Cornwall describes how how reframing development as a “global quest for social, gender, racial and ecological justice” makes it possible to envision a decolonised approach to development studies in its entirety:

It would focus on understanding the makings of the modern world as a process deeply inflected by the colonization of minds as well as lands, with indelible marks on world history, including in places that were never part of the colonial dominion or colonizing project. It would seek out and situate attempts to change the world for the better, locating them not in the narrative of intervention, but in one that includes insurrection. (Cornwall, p.202).

Surveying the development landscape midway through this decade, Sumner’s schema is a useful reference. Since reading the paper, I have found myself considering which quadrat the communications and public positioning of development NGOs, ‘thought leaders’ and activist groups, and academic discourse would fall into. However, as Sumner notes, it is one interpretation and by no means a final framing of the development picture today.

This blog has set out to critically consider the place of development studies and how its teaching and practice can help bring about meaningful change. The ‘post-development’ quadrant of Sumner’s typology spotlights a vital area of focus in terms of realising true change and decolonisation in the development space. Discussions on the ‘future of development studies’ continue, but the need for truly decolonising initiatives and transformative approaches in communicating social change are clearer than ever.

References

Biekart, K. Camfield, L. Kothari, U. & Melber, H. (2023). Rethinking Development and Decolonising Development Studies. In Challenging Global Development: Towards Decoloniality and Justice. (pp. 1-13). Cambridge: Palgrave Macmillan.

Cornier, C. (2024). The Future of Development Studies: Unity in Diversity? Retrieved December 2 2024, from https://www.developmentresearch.eu/?p=1915

Cornwall, A. (2020). Decolonizing Development Studies: Pedagogic Reflections. In D. Bendix, F. Müller & A. Ziai (Eds.) Beyond the Master’s Tools? Decolonizing Knowledge Orders, Research Methods and Teaching (pp. 191-204). London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Moyeen, A. & Muzaffar, S.K. The Future of Development Studies – Further Discussions Needed. Retrieved December 2 2024, from https://www.developmentresearch.eu/?p=1951

Sumner, A. (2024). Unity in Diversity? Reflections on Development Studies in the Mid‑2020s. The European Journal of Development Research. 36:1280–1298.

Telleria, S. (2023). Essentialist Approaches to Global Issues: The Ontological Limitations of Development Studies. In Challenging Global Development: Towards Decoloniality and Justice (pp. 15-33). Cambridge: Palgrave Macmillan.

This is a really interesting look at the crossroads facing development studies. You are using a smart way of grouping different ideas to help us understand them. I particularly appreciate the emphasis on moving beyond “development” as a label and use words like “global justice” and “global equality” instead. This change could help everyone agree and work together to make the world a fairer place.

How do you think we can try to ensure that the voices and experiences of those most marginalized are centered in the process of redefining and decolonizing the field?