By Jessica Saler

As natural disasters, conflict, and poverty have consumed our world for centuries, approaches to development have had to adapt and change. The traumatic experiences create cycles of human, social, and economic distress and suffering, making development projects limited to their long-term sustainability. During the 1970’s, the idea of trauma-informed care (TIC) emerged, with the idea that development projects of any kind should be cognizant of the trauma within your community, the impact of trauma on the physical and psychological body, and actively integrate strategies to avoid re-traumatization of victims.

How can we implement trauma-informed care into communication methods within development projects? Well, we can look at USAID and World Vision’s work in Ethiopia and their implementation of TIC into their literacy and educational development project in Ethiopia. Their success with this project should be an example of not only using more current approaches to development, but also an example of how development approaches need to be adaptable and understood as fluid strategies.

USAID launched the READ II project to increase accessibility to literacy and education. However, after an outbreak of armed conflict in November 2020 (which was the same year the globe was surrounded by the COVID-19 pandemic), the type of literature and educational materials shifted to a focus on Education in Crisis and Conflict (EiCC) and implemented a trauma-informed lens to ensure that recovery was supported, and Ethiopians would not be retraumatized. World Vision partnered with them at this point to help refocus their efforts in an effective way. (World Vision, 2023).

After 3 years, there were multiple successful initiatives run through READ II, using literature as a way of communicating support, psychological recovery, and development. Some of these successes included:

– Psychological first aid training for community members, allowing them the knowledge to support one another for generations to come.

– 26 reading camps were implemented for children, with the literature supporting psychological and emotional needs of the children who are out of school and/or displaced from the conflict .(World Vision, 2023).

Knowing that accessibility to the literature was available, but many were illiterate, they also implemented foundational programs to help those who can’t read. This included:

– Engaging 11 000 community leaders to help teach children to read.

– Mobilized workshops to help more than 38 000 parents create reading habits at home. (World Vision, 2023).

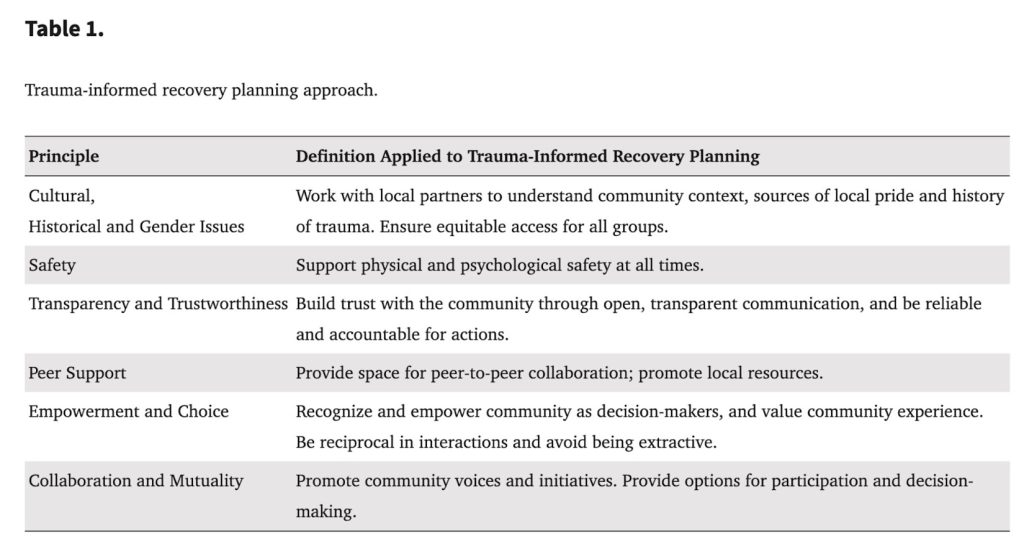

And of course, when COVID-19 shut down schools, they were able to continue using literature to support recovery efforts by adapting their programs and ensuring that their educators were always mobile and accessible, and engagement with community members continued. As a big reader myself, this made me realize that knowledge truly is power, and the ability to communicate through written pieces frees us of time and space constraints that learning in-person or verbally would have. They used interdisciplinary practices to adapt, which UNICEF’s handbook to trauma-informed development states that it requires open listening to victims, understanding the impact of trauma, designing strategies that consider the trauma and avoid re-traumatizing communities, and considering all of this when making decisions (Valgiusti , 2022, p. 63).

We can see that USAID and World Vision not only adapted their project to the needs of the community, but they did not try to be “saviours” or experts, instead educating community leaders who can then educate others long-term. This is important in decolonization, anti-oppression, and trauma-recovery efforts. In fact, this method of anti-oppression development is seen in other projects across the globe where “the role of the NGO changed according to the desires and requirements of the networks, their task being redefined as putting community groups in contact with one another…” (Melber et al., 2024, p. 43).

We should use this project as an example of emerging practices and understandings of development work, and implement it into future generations’ education of development studies. Anke Schwittay (2024) argues that “integration of knowledge and expansion of work experiences locations, spaces, and pathways can contribute to reframing International Development from a practice of expert saviourism rooted in colonial legacies to a project of global solidarity and justice” (p. 253). We need to prioritize more modern approaches of understanding and practicing development, such as USAID and World Vision’s shift from standard education and literacy efforts to trauma-informed care that uses education and literacy to help communicate support and recovery efforts and implement them into the students’ practical experiences.

As Bendix et al. writes, “if teaching development studies could be about transformative education that ignited a generation of global citizens who were unafraid to look deeply at the causes of injustice, come to terms with their own privilege, and learn how to listen and act with compassion and humility, I can’t help thinking the world would be a better place.” (2020, p. 202).

Sources:

Bendix, D., Müller, F., & Ziai, A. (2020). Beyond the master’s tools?: Decolonizing knowledge orders, research methods and teaching. Rowman & Littlefield.

Melber, H., Kothari, U., Camfield, L., & Biekart, K. (2024). Challenging global development: Towards decoloniality and Justice. Palgrave Macmillan.

Rosenberg, H., Errett, N. A., & Eisenman, D. P. (2022). Working with disaster-affected communities to Envision Healthier Futures: A trauma-informed approach to Post-Disaster Recovery Planning. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(3), 1723. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031723

Schwittay, A. (2024). University work experiences in international development: Expanding locations, spaces and pathways. Progress in Development Studies, 24(3), 252–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/14649934231211676

Valgiusti, F. (2022, April). Trauma Informed Approach: Introductory Handbook. UNICEF. https://www.unicef.org/northmacedonia/media/12261/file/Trauma%20Informed%20approach.pdf

World Vision USA. (2023, September 1). Restoring hope: Innovative community solutions for healing and learning in Ethiopia. LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/restoring-hope-innovative-community-solutions-healing-learning/

Hi Jessica,

This is one of my favourite posts on our blog. One of the reasons is that even though I have been writing words like “alternative pathways to development” or “innovative” development models etc., I would still wonder what they were and how they were being used in the field. I did read about a few radical approaches in Melber et. al’s book but they seemed really complex and had no practical context to it. Also, I’ve been reading about how the young generation in India and Japan aren’t interested in books. And I was wondering whether reading as a practice was getting replaced by other ways of consuming content, especially when we talk about the general public. However, your case study helped me put some things into perspective. Thank you!