By Anubhuti Vashist

Ethics for Strong Qualitative Research

Ethics form an essential component of research. Describing ethicality as one of the “Big-Tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research, Sarah J. Tracy (2010) argues that “ethics are not just a means, but rather constitute a universal end goal of qualitative quality itself” (p. 846). This perspective views ethics and accompanying practices as prerequisites at every step of the research process, from beginning to end. While discussing the role of a variety of ethics (procedural, situational, relational, and exiting) in research, Tracy (2010) writes that qualitative researchers are actively engaged in co-creating meanings along with the participants within the realm of ethicality (p. 847-848).

Researchers ensure ethicality in their work by engaging in practices that safeguard participants from harm at any time. According to Tracy (2010), researchers must maintain a critical outlook to evaluate their actions concerning the participants, provide necessary closure, and anticipate misuse or misappropriation of their findings. Conducting ethics-focused qualitative research necessitates building a friendly rapport that supports well-being and empathy. For instance, when interviewing participants, researchers are not merely engaged in a mechanical process of asking questions and recording answers. They must also work hard to create a safe, healthy environment free of insensitive and inconsiderate actions or attitudes.

Informed Consent: “A yes, and then what?”

One of the stages where ethical engagement becomes crucial is in the context of data. How the data is obtained, preserved, and used are the three critical aspects that qualitative researchers need to account for early in their research journey. Apart from ensuring the privacy and confidentiality of research participants or contributors, qualitative researchers should obtain “informed and voluntary” consent from each respondent (Israel & Hay, 2008, p.431).

It is important to note that informed consent does not stop at securing agreement of research participation; it is an ongoing process that protects the participants’ will throughout the research. Mark Israel and Iain Hay (2008) report that many scholars view informed consent as a “dynamic and continuous” process (p. 431) that encompasses much more than the initial ‘yes’ obtained from the participants. According to the authors, consent should be sought after making the participants fully aware of the project’s aims and objectives, the duration of the interview process, potential risks and benefits, and details about the organizations directly or indirectly involved in the research (p. 431).

Researchers must provide as much relevant information to their participants as possible. While what constitutes ‘relevant’ information is subjective, any detail that could turn a ‘yes’ into a ‘no’ should be disclosed to ensure participants understand what they have agreed to. Additionally, researchers should address any concerns or doubts of the participants to make the process fair.

When the bookish Ethic meets the rowdy Field

Ethics are easier read than done.

Time, weather, participants’ everyday routines, and the researcher’s or participants’ mental or physical health during the interactions are some of the many factors that can interfere with ethical conduct. It does not take long for the naive researcher to realize that reading about ethical guidelines, standards, and codes of conduct within the controlled, structured, and safe environment of academia—comprising familiar faces and well-defined roles —is vastly different from engaging in ethical practices in the vibrant, dynamic, and ever-changing field– filled with strangers who have varying levels of interest in the researcher as much as she has in them.

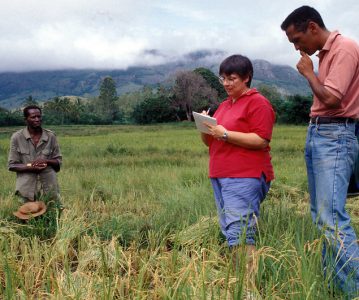

In the field, researchers must rely a lot on the context and their decision-making skills to ensure no breach of ethics. The researcher will have to make tough decisions to prioritize the well-being of participants, especially children, over the immediate benefits of their participation in the research project. This decision-making at a personal level was the central point of the webinar conducted by the visual content production global agency Fairpicture on 4th September 2024.

Part of their #FairTalk series, the webinar “Informed Consent–Balancing Efficiency and Ethics” focused on the complex realities and challenges faced by visual creators working with development or private organizations. The discussion by panelists highlighted the ‘invisible’ power dynamics between the researcher/organization/local gatekeepers and the participants in the field. As per the panelists, creators and researchers must be aware of and work to transgress the power hierarchies in the field, especially when working with marginalized communities, as they can interfere with the fairness of the consent process. For instance, Kari Brayman, Senior Content Manager at Vitamin Angels, explained how sitting at a level below participants allows her to present herself in a non-intimidating manner.

Drawing from personal experiences, the panelists highlighted how ethics exist in a contentious relationship with the diverse social and cultural dynamics that inform the field. Brayman asserted the urgency of a mindset shift within the development sector that prioritizes participants over project aims. Emphasizing quality over quantity in the number of participants interviewed or photographed, she stressed the importance of building considerate, empathetic, and meaningful relationships during interactions.

Another panelist, Josemarie Nyagah, a visual creator with Fairpicture, pointed out the hidden challenges of obtaining consent. She explained how creators and researchers should only accept a ‘Yes’ after critically reflecting on whether the participants fully understood how the creators or interviewers would use their pictures or information provided by them. Nyagah further explained the sense of fear, shyness, or conformity that can lead participants to agree without fully understanding the implications of the creator/interviewer’s request. The panelist stressed the importance of building a friendly rapport that helps the participants feel comfortable raising their concerns.

Conclusion: Ethics in Development Research

The webinar held valuable insights for students studying Development Communication as the field entail an active engagement with the concerns of vulnerable communities and disadvantaged groups. The zeal to create a positive social impact by participating, exploring, documenting, and sharing as a volunteer, researcher, or storyteller requires a commitment to ethical conduct. A decolonial approach to development has shed light on how ethics have been compromised in the attempt to ‘do good.’ Critical reflection on ethical practices is crucial to counteract the dominant tendency in the international development sector to think for others and speak on their behalf.

It also does not help that the field, for a long time, had shielded itself from the concerns of postcolonial scholarship (McEwan, 2019, p. 149). Critiquing development as an ideology that clings to (neo) colonial ways of understanding the non-Western world using stereotypical ways of knowing and communicating, K. Biekart et al. (2024) write:

“Development has been founded upon the forging of dichotomies, be they geographical, spatial, material, cultural, or temporal. This has led to identifications, classifications, and categorizations of people and places using racialized, gendered, pseudo-cultural, and ethnic binaries” (p. 4).

The understanding of development as a concept that is a product and promoter of asymmetrical relations of power has led to calls for the decolonization of development studies within academia. Ziai et al. (2020) concur that decolonization involves identifying and resisting “colonial continuities embedded not just in the epistemic foundations and thematic concerns but also in the actual practices, that is, the craft of research as canonized in research methods and methodologies” (p. 3). Ethical practices, too, fall within the purview of these attempts by post-development and decolonial scholars to rethink research in development studies.

For instance, Indigenous researcher Lauren Tynan (2024) outlines the similarity between colonial rule and Western research practices by highlighting their extractive treatment of non-Western and/or Indigenous life-worlds and knowledge. On the other hand, she advocates for respectful and accountable relationships with participants. Establishing healthy social relationships with participants require students to re-imagine research terminologies and data collection practices.

Reflecting on her PhD experiences, Tynan writes: “The field is a place of relations. It is not a research location to fly in and fly out of.” (p. 145). To see a field as a “place of relations” rather than a geographical point where the participants reside would also allow the researchers to acknowledge the contribution of their participants. Most importantly, the researcher ceases to be an extractor of knowledge for a self-serving motive–academic recognition gained from publishing a paper or an academic degree after writing a dissertation– and positions oneself as a “supporter/advocate/ally” (Schwittay, 2024, p. 253).

References

Biekart, K., Camfield,L., Kothari, U., & Melber, H. (2024). Rethinking Development and Decolonising Development Studies. In H. Melber, U. Kothari, L. Camfield, & K. Biekart (Eds.), Challenging Global Development: Towards Decoloniality and Justice (pp. 1-13). Palgrave Macmillan.

Cheryl, McEwan (2019). Postcolonialism, Decoloniality and Development. (2nd edition). Routledge.

Israel, M. & Hay, I. (2008). Informed Consent. In Lisa M. Given (ed.), The Sage Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods (Vol. 1 & 2) (pp. 431-432). Sage.

Schwittay, A. (2024). University Work Experiences in International Development: Expanding Locations, Spaces and Pathways. Progress in Development Studies, 24, 3, 252–267. DOI: 10.1177/14649934231211676.

Tracy, S.J. (2010). Qualitative Quality: Eight “Big-Tent” Criteria for Excellent Qualitative Research. Qualitative Inquiry,

16(10), 837–851. DOI: 10.1177/1077800410383121

Tynan. L. (2024). Data Collection Versus Knowledge Theft: Relational Accountability and the Research Ethics of Indigenous Knowledges. In H. Melber, U. Kothari, L. Camfield, & K. Biekart (Eds.), Challenging Global Development: Towards Decoloniality and Justice (pp. 139-164). Palgrave Macmillan.

Ziai, A., Bendix, D., & Müller, F. (2020). Decolonizing Knowledge Orders, Research Methodology and the Academia: An Introduction. In D. Bendix, F. Müller & A. Ziai (Eds.), Beyond the Master’s Tools? Decolonizing Knowledge Orders, Research Methods and Teaching (pp. 1-15). Rowman & Littlefield.

Hi Anubhuti,

I feel very aligned with the reflections shared in this post—thank you for such a thoughtful write-up! Having worked at a research center myself, I’ve experienced how acting ethically in the field can depend on so many factors, from the dynamics with participants to logistical constraints. I really appreciated how you emphasized the field as a “place of relations” rather than a location to simply visit and leave. This resonates deeply because, during times when I had to undertake many field trips, I sometimes found myself exhausted, which made it even harder to sustain the kind of relational engagement that ethical work requires.

Your discussion made me wonder: how can researchers balance the practical demands of data collection with the ethical commitment to build relationships, especially when time and resources are limited?

Thank you Lan Chi for your comment 😊 I’m glad that you liked the post ♥ I can too relate with your experience. Feeling exhausted and drained is quite common and it does impact our ability to engage ethically with the participants. I think this is one of the most practical and complex realities on the field, that I guess we learn to handle with experience. I understand that with limited time and resources the task becomes really hard, however, if we are to really embrace research that is anything but extractive in nature we might have to look elsewhere. Where? I am yet to figure that out personally. But scholars, especially decolonial scholars, put their faith in alternative ways of doing research that give equal visibility to the participants. But we do have a long way to go in figuring out ways to make this possible and it all starts with questioning and challenging the current practices.