By Liam Corcoran

At the two day Humanitarian Congress in Berlin last month, a wide range of crucial topics were up for discussion, from increasing attacks on medical aid missions to discussion of ongoing crises in east DRC, Sudan and the challenges facing refugees at Europe’s borders. Speakers included staff from international NGOs, academics, voices from civil society, politicians and more.

Of much interest for the subject matter relevant to this blog was the opening ‘keynote dialogue’ on the current international humanitarian landscape and pressing concerns. The discussion featured Heba Aly, Coordinator for the UN Charter Reform Coalition and former editor of The New Humanitarian and Nimo Hassan, Director of the Somali NGO Consortium. Their talk largely focused on global governance reform, the challenges facing humanitarian organisations and reimagining crisis response by INGOs.

Humanitarian Congress Stream: Keynote address from Heba Aly and Nimo Hassan starts at 11 minutes.

“What do you do when you can’t help everyone?” asked Heba Aly in her opening remarks. “Is the concept of triage the way to proceed?”

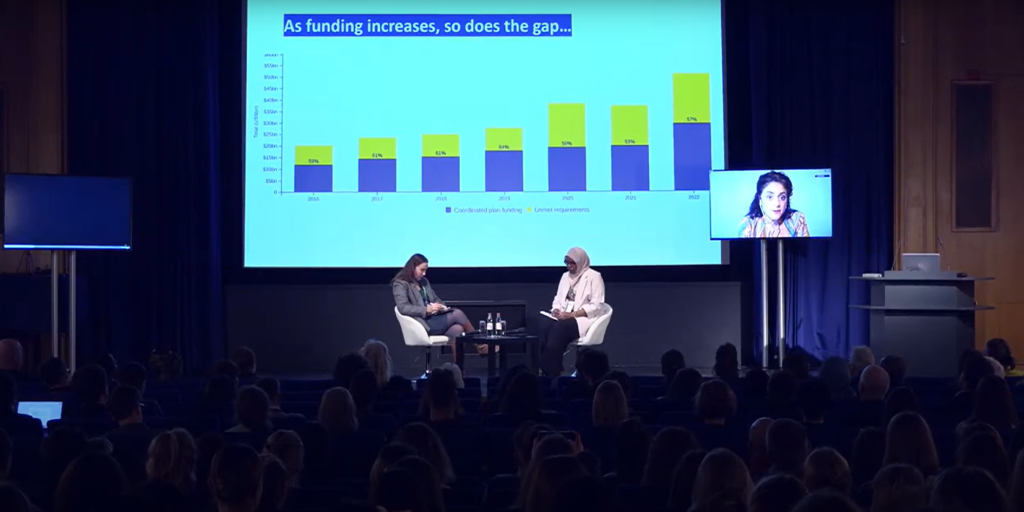

The backdrop to the discussion was the myriad of challenges facing international humanitarian response, including conflict, growing geo-political tensions and accelerating climate change effects. Added to that are dwindling financial commitments from wealthier nations to international funding appeals. By mid-November, just over 40% of total annual funding required for global crises in 2024 had been met, according to OCHA.

Aly argued that in a reality where international funding targets for humanitarian crises are consistently not met, an ambitious rethinking of the role of INGOs in crisis response appears necessary. For Aly, humanitarian bodies should move away from simply seeing their response as being supply-driven and recognising that sometimes their most valuable contribution could be to advocate for solutions to the crisis in the first place.

“My take is that in an age where there are not nearly enough resources to respond to all these crises… Instead of constantly playing catch-up or having to make tough triage choices, humanitarians could turn to tools other than humanitarian aid. With a smaller amount of money, you may well have more impact through advocacy about the larger problem, than by saving half of those who need help, in order for them to find themselves back in crisis the next day,” she explained.

In this vision, humanitarian organisations are forced to think more broadly about responses to crises, beyond aid itself. Aly gave the following possible responses: “Amid the Pakistan floods, the best crisis response may have been advocating for debt relief. In DRC, it could be advocating for asylum in Europe. In Gaza, it’s very much a vote at the Security Council.”

The operational challenges involved here for a true transformation in the sector; a reorganisation of how INGOs work, and a transition in doing to enabling others to do. “In the short term, some needs being met by INGOs may not be met, while in the long-term, organising INGOs around being able to enable the response of local communities, I think, will save many more lives,” asserted Aly.

“Humanitarian principles are a means to an end, they are not an end in themselves… at the moment, being neutral is not guaranteeing access in a majority of countries… Counterintuitively, being more political may actually improve humanitarian access in certain crises because it will increase legitimacy, trust and reduce scepticism. In a lot of countries today where local communities are sceptical of aid workers, it is because they don’t see that those aid workers are actually invested in their cause.”

Localisation, which has been a topic of conversation in different ways in humanitarian practice for a number of years, also has an important role in this process. In essence, localisation advocates for more funding and decision-making power to be centralised in communities in need of a humanitarian response.

Obstacles undoubtedly remain to meaningful implementation. A May 2024 article in the Guardian reported how just 2.1% of donor money goes to local organisations, either directly or indirectly. As noted earlier, international funding is a wider issue, but is financing of localisation efforts. Localisation is now frequently evoked in debates around the reimagining of international development, but questions remain, mostly about the extent to which power dynamics (including funding and political support) can, or even should, be transferred within the aid system from north to south. As noted in the new open access book Challenging Global Development: Towards Decoloniality and Justice:

“…localisation itself rests on an implicit binary between northern donors and southern recipients, often involving a poor conceptualisation of the local, and echoing colonial spatial relations and power inequalities.” (Biekart, Camfield, Kothari & Melber, 2024)

Meanwhile, in a field that has long prioritised official impartiality and neutrality, explicit political advocacy comes with its own uncertainties, as several audience members noted, particularly in what they could mean for staff access and security. Major international humanitarian organisations including the ICRC and UN agencies usually carefully adhere to political neutrality publicly, whilst using diplomatic and bilateral connections to progress their operational priorities behind the scenes. Aly agreed that the approach does not have to be adopted by all agencies; it seems there will always be a need for the impartial ICRCs of the world.

Yet Nimo Hassan of the Somali NGO Consortium urged participants at the Congress to reflect on how the international humanitarian system can be reshaped. “We must position ourselves better and ensure that affected communities remain at the very heart of our response… People in need, people in crisis, need to be in the centre when and if we are redefining the way we respond.” Such change requires commitment to meaningfully engage in structural change and reimagining power relations in the humanitarian and development sectors.

Despite events like the Humanitarian Congress sometimes appearing as a ‘talking shop’ in which big structural problems are endlessly debated without tangible outcomes, they also carry a structural weight. This was evidenced by the participation of numerous representatives from the German government, one of the largest humanitarian donors in the world. Whether the suggestions offered by panellists have an effect on implementation by those in positions of authority within humanitarian organisations remains to be seen.

As Nimo Hassan noted, for communities affected by crises, the implications of these discussions are not abstract, but often a matter of life or death.

References

Melber, H., Kothari, U., Camfield, L., & Biekart, K. (Eds.). (2024): Challenging Global Development: Towards Decoloniality and Justice. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.