Estimated reading time: 11 minutes, 7 seconds.

For a recent blog post, I wrote about cryptocurrencies and their potential for development. Initially put off by the risks – such as volatility, security concerns and its association with criminality – organisations have begun to embrace cryptocurrencies in the last few years; for example, accepting them as donations and taking advantage of their global nature, free of international transaction fees. But in researching this topic, it became apparent that there is a limit to what cryptocurrencies can offer, and that the underlying technology, blockchain, has more potential uses for development. Blockchain goes beyond currencies; in effect, any unit of value can be transacted on blockchains (Hernandez, 2017). For this blog post, therefore, I will delve deeper into the world of open data and blockchains: First, I will refer to core literature in introducing the concept of open data and what it means for international development; secondly, I will outline what blockchains are and discuss examples of how blockchain is already being used in the sector, as well as its benefits and limitations. Finally, I will draw conclusions on the potential of blockchains to achieve development goals.

Development 2.0 and open data

In his book Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D), Heeks (2017) refers to ‘Development 2.0’ as underpinned by forces that shape Web 2.0, such as large-scale data, openness, the power of the crowd and network structures. Regarding the latter, he says, “flat network structures provide an alternative to hierarchical structures in which there is some central control point. Where the former replaces the latter then it can involve (…) the removal of some previous intermediary” (Heeks, 2017, pp. 326-327). As the production of data greatly increased, data became trendy in the 2010s, and a ‘data revolution’ was even named as a requirement to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals, as well as to measure their achievement. This led to the creation in 2015 of the Global Partnership for Sustainable Development Data, which aims for a more data-driven approach to international development (p.330). One data-intensive development innovation is ‘open data for development’, which is the greater availability of development-related datasets for general use. According to Heeks, open data can be linked to improvements in transparency and accountability. It can also empower decision-makers at various levels of development, from individuals and communities to civil society organisations, to make better decisions (p. 337).

Heeks also points out several challenges for Development 2.0, however, including social and technological divides, which raise barriers to inclusion, and data quality and quantity in developing countries; for example, incomplete, inaccurate or biased data (Heeks, 2017, pp. 328-329, 338). Many data-intensive development initiatives also lack direction, focusing on gathering and processing data without a clear sense of how it is going to be used to deliver development results, or struggling to move beyond making data available. This comes from a misguided belief that “data alone can somehow lead to better development” (p.340). Reade, Taithe and MacGinty (2016) agree with this: “(D)ata is not knowledge, nor is it the capacity to analyse it” (p.2). They argue that many development initiatives seem to be driven by what is possible rather than what is needed and warn against collecting data for data’s sake.

Blockchain for development

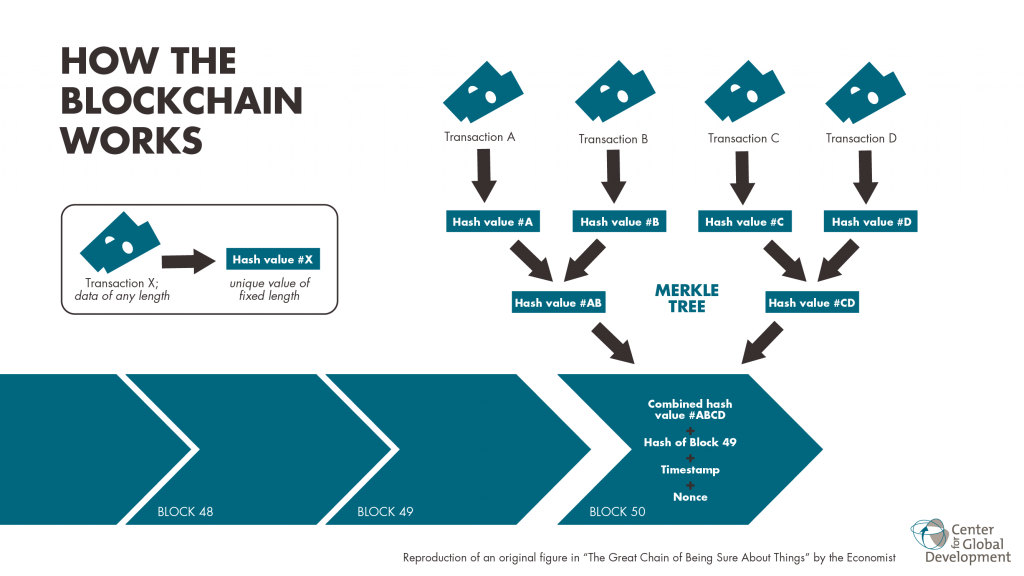

Blockchain is a public, decentralised database. Essentially, it is a digital ledger of transactions that is distributed, verified and monitored by multiple sources simultaneously (Hernandez, 2017). This is interesting because, as Adamson (2017) puts it:

“Blockchain (…) enables multiple cooperating but non-trusting parties to have a single source of truth, without the need for a centralized or third-party arbiter of that truth. Because each successive block or record in the chain contains data from previous blocks it can be virtually immutable, trustworthy and transparent.”

– Adamson, 2017

In this way, blockchain is aligned with Development 2.0, in that its networked nature eliminates the need for a central control point (in the case of cryptocurrencies, the banks), and it is open and transparent (public and immutable).

In recent years, many international development organisations have launched projects using blockchain in different ways, but many blockchain-based initiatives are still in their infancy and may take years to be tried and tested. Some of the ways blockchain is being used or is proposed to be used are:

- Making supply chains transparent: Blockchain technology is being used to allow consumers to track the origin of products, such as coffee and coconuts, and to ensure that farmers are given a fair wage for their produce (Nyamadzawo, 2017).

- Protecting land rights: Blockchain is being used in the area of land registry to protect land rights and reduce corruption in the land sector. These land registries can allow people to search, manage, and verify property and land documents such as site plans, indentures, and mortgages (Thomason, 2017).

- Passing funds to beneficiaries: The UN World Food Programme (WFP) developed the Building Blocks programme, a blockchain system which uses the biometric registration data of refugees in Jordan’s Azraq refugee camp so that they can purchase products in the camp’s supermarkets using an iris scan payments system instead of vouchers or cash. It has also improved how WFP accounts for transactions (Nyamadzawo, 2017). Organisations are also using blockchain and cryptocurrencies to transfer funds to developing countries, for example to schools, ensuring transactions are secure and funds are used for their intended purposes. The money saved on international transaction fees means more funds go directly to humanitarian aid (Nyamadzawo, 2017).

- ‘Banking the unbanked’: Financial services (‘fintech’) is the fastest moving sector for blockchain (Thomason, 2017). Peer to peer payment systems are being developed using blockchain technology to provide communities access to control their money digitally (Nyamadzawo, 2017). Banqu is using blockchain technology in Indonesia to offer banking services to refugees, the displaced, and poor communities.

- Allowing low-cost remittances: CASHAA is a blockchain-based financial service that helps complete mobile cash transfers with zero fees (Thomason, 2017).

- Enabling peer-to-peer energy trading: This allows people to both access renewable energy and trade it. Solar startups produce low-cost solar panel solutions for off-grid, rural areas, and in Bangladesh, for example, SOLshare offers a blockchain-based service to allow solar producers to sell solar electricity to their neighbours: “If a user needs electricity, they simply add bKash, the country’s largest mobile banking network, credit to their mobile wallet, turn their SOLbox to “buy mode” and trade credit for power, for those looking to sell electricity, they simply switch the box to “sell mode.” The credit in the mobile wallet can be used to purchase goods at local stores” (Thomason, 2017).

- Tackling a global pandemic: In 2020, since the global coronavirus pandemic began, there have been many ideas for how blockchain technology could help fight the virus, such as apps for monitoring the health of individuals and communities and new approaches for simulating the spread of COVID-19 (Amoils, 2020). Other ways include connecting health providers with suppliers of medical equipment and validating a person’s immunity to the virus (Castellanos, 2020).

- Automating processes: If cryptocurrency was Blockchain 1.0, ‘smart contracts’ are Blockchain 2.0 (Zwitter & Boisse-Despiaux, 2018). They are essentially bank accounts for contracts that live on blockchains containing programming code, making it possible to automate processes such as aid payments and supply chain management. For example, they could be used to automatically disperse funds once predetermined conditions are met, which could help improve response times in humanitarian emergencies (Hernandez, 2017).

Blockchain 2.0

This new era of blockchain, Blockchain 2.0, seems to resolve many of the risks and pitfalls that cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin brought with them (Zwitter & Boisse-Despiaux, 2018), making it safer for development organisations to associate themselves with. Furthermore, blockchains can be designed to be either public or private. Private, or ‘permissioned’ blockchains are operated by one organisation or group of organisations and are only accessible to other groups or organisations that have been granted permission to use them. These have garnered interest from development organisations wishing to use them to collaborate with partners, for example, and they represent an easier starting point for these organisations to engage with blockchain (GSMA, 2017, p.6).

But blockchains themselves can bring with them many technical challenges. For example, in applying blockchain technology to improve agri-food traceability, Feng, Wang, Duan, Zhang and Zhang (2020) highlight challenges such as interoperability and standardization between ledger types (eg. public and private) and how to ensure continuous stability and security of blockchain based applications, as well as social and institutional challenges such as legal and regulations issues (pp.12-13). Blockchain is also a very high energy consuming technology, as it will always require servers and computers to process transactions (Zwitter & Boisse-Despiaux, 2018). Along with the need to weigh up the benefits with these high energy costs, in countries where there is little or inconsistent internet connectivity, there is a limit to the scalability of blockchain projects.

Data is not knowledge

Earlier in this post, I outlined some challenges with development and open data, and blockchain is no exception to these. Much more work needs to be done to make a blockchain-based initiative work, aside from setting up the technology. Data can be of varying quality, or not available at all, as I learned from the Lebanon case study in my previous post about tackling misinformation around COVID-19. There is also the wider social context to take into account. As Hernandez (2017) states, when a blockchain is used to tackle social issues, “there are political issues and power relations that need to be overcome before, during and after implementation. Tackling these often takes much longer than implementing the technology itself. Timeframes for projects should take into account these factors, and not simply assume that delivering the technology will be the end of the intervention” (p.2). Smart contracts, for example, just execute code; they still must be legal, and much thought needs to go into any ethical implications of using them to achieve a certain goal. Moreover, given their rigid coded nature, it may be difficult to tackle complex development issues that require continuous adaptations.

Digital inequalities remain

Social and technological divides, and inclusion, also need to be considered when it comes to blockchain-based initiatives, just as they do with any technology project. Solutions need to be designed with digital divides and inequalities in mind, which often reflect wider societal inequalities:

“Citizens in poorer countries, those in rural areas, or marginalized groups are less likely to be online or have the digital literacy required to engage with blockchain-based technologies, which can therefore potentially exacerbate digital inequalities.”

(Hernandez, 2017, p3)

The use of cryptocurrencies for development has been accused of ‘techno-colonial solutionism’; for example, by encouraging people in developing countries to opt for an alternative banking system instead of strengthening those vulnerable countries’ regular banking systems (Scott, 2016, p.13). Similarly, Hernandez (2017) argues that as with all disruptive technologies, it’s through adding value to existing development processes that blockchain has more potential to be successful (p.4).

The hype around blockchain in the international development sector has led to it being thought of as a solution in search of a problem. It’s therefore essential that a plan is in place for any given project, for how the blockchain will be used to tackle a development challenge and achieve its goal, and as Adamson (2017) writes, successful proofs of concept require that blockchain’s characteristics are well matched to the specific challenge it is aiming to meet.

In conclusion, like other much-hyped ‘disruptive’ technologies, blockchains are not a solution in themselves for development challenges, but they do have potential when used as part of well-planned projects that take into account the costs and benefits of using blockchain, as well as the context in which they are operating, and build on existing development processes. Blockchain-based initiatives take time to plan and implement well, and organisations are still in the learning phase. When researching this topic, block-chain based project results and outcomes were difficult to come by, which is telling. It will most likely be a few more years before the real impact and potential of blockchain in development can be seen.

Personal reflections

The New Media, ICT and Development module has not only made me reflect on how to write about topics from the ‘social media, datafication and development’ theme in an engaging, succinct and accessible way, but also on making my posts relevant to current ICT4D trends and discussions, drawing from recent research and journalistic pieces. Having written online content before for a nonprofit organisation, and knowing the principles – for example, search engine optimization, the use of plain English and the need to keep the audience in mind – it was an interesting exercise to do the same within an academic setting. I deliberately chose topics I knew little about, so I gained a wealth of knowledge about how technology, data and platforms can be used on the ground in the developing world, but also about their limitations, particularly within the wider socio-economic context. I learned how Facebook’s internet.org project is an example of digital colonialism and raises the ethical question of corporations’ role in development. I learned about how vital it is to have a smartphone as a refugee, and how the factors that determine what access a refugee has to mobile technology and the internet largely depend on their socio-economic status over their refugee status. I learned about the limitations of social media on its own when it comes to rural communities fighting COVID-19, and how it is often combining this with offline communications that achieves the best results. And I’ve learned how the success of projects using blockchain technology often depends on wider societal factors and taking these into account in the project design.

References

Adamson, G. (2017). Opinion: In developing economies, blockchain’s benefits and risks depend on the application. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.devex.com/news/opinion-in-developing-economies-blockchain-s-benefits-and-risks-depend-on-the-application-90138

Amoils, N. (2020). Innovation In Crypto Charitable Efforts For Coronavirus. Retrieved October 16, 2020, from Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/sites/nisaamoils/2020/05/05/innovation-in-crypto-charitable-efforts-for-covid-19/#53274d46f641

Beraldo, D. & Milan, S. (2019). From data politics to the contentious politics of data, Big Data & Society, 6(2).

Castellanos, S. (2020). A Cryptocurrency Technology Finds New Use Tackling Coronavirus. Retrieved October 16, 2020, from The Wall Street Journal, https://www.wsj.com/articles/a-cryptocurrency-technology-finds-new-use-tackling-coronavirus-11587675966

Cinnamon, J. (2020). Data inequalities and why they matter for development. Information Technology for Development, 26(2), 214-233.

Feng, H., Wang, X., Duan, Y., Zhang, J., Zhang, X. (2020). Applying blockchain technology to improve agri-food traceability: A review of development methods, benefits and challenges. Journal of Cleaner Production, 260.

Graham, M., Hjorth, I., & Lehdonvirta, V. (2019). Digital labor and development: impacts of global digital labour platforms and the gig economy on worker livelihoods. In M. Graham (ed.) Digital Economies at Global Margins (pp. 269-294). Ottawa, ON/Boston, MA: IDRC/MIT Press.

GSMA. (2017). Blockchain for Development: Emerging Opportunities for Mobile, Identity and Aid. London: GSMA.

Heeks, R. (2017). Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D). Abingdon: Routledge.

Hernandez, K. (2017). Blockchain for Development – Hope or Hype?. IDS Rapid Response Briefings, (17).

Nyamadzawo, T. (2017). 4 ways blockchain is being used in international development. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.bond.org.uk/news/2017/09/4-ways-blockchain-is-being-used-in-international-development

Read, R., Taithe, B. & Mac Ginty, R. (2016). Data hubris? Humanitarian information systems and the mirage of technology. Third World Quarterly, 37(8), 1314-1331.

Scott, B. (2016). How can cryptocurrency and blockchain technology play a role in building social and solidarity finance? (UNRISD Working Paper, No. 2016-1) Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development (UNRISD).

Thomason, J. (2017). Opinion: 7 ways to use blockchain for international development. Retrieved November 10, 2020, from https://www.devex.com/news/opinion-7-ways-to-use-blockchain-for-international-development-90839

Zwitter, A., Boisse-Despiaux, M. (2018). Blockchain for humanitarian action and development aid. Journal of International Humanitarian Action, 3(16).