As Haiti once again finds itself on international news reports, it seems it is a good time to discuss to what extent Haiti’s struggle may be at the hands of the international community.

Dubbed “the republic of NGOs”, Haiti attracts a lot of attention but for all the wrong reasons. With the highest concentration of international NGOs, vast amounts of foreign aid (particularly since the 2010 Earthquake) amounting to an estimated 13 billion between 2010-2012 (though there are little shared baseline statistics which leaves space for questioning), and longstanding presence of international community, ongoing crises and a plethora of scandals.

Remarkably, despite the heavy international intervention, pooling of resources and continued programs, the current state of the country is of high dependancy:

• As the poorest country in the western hemisphere, food insecurity affects 40% of the 11 Million population, and in 2020 70% of the population is unemployed, 74% are living below the poverty line, and 51.3 % are illiterate

• Haiti’s government is highly dependent on outside funds: 93% of health and education is private and/or managed by ngos due to the governments incapacity to provide even the most basic needs. Foreign aid accounts for 60% of the annual national budget, and 30% of the country’s GDP comes from remittances.

• Indeed, Haiti attracts a great amount of external financing in the form of international aid, it is estimated that the total funding disbursed since 2010 by the bilaterals and multilaterals is USD 6.43 billion added to resources contributed to the NGO community USD 3.06 billion, totalling USD 9.49 billion (Special Envoy to Haiti). It is notable however that the center for economic and policy research marks aid disbursed by donors since 2010 at USD 7,538,885,632.

Statistical sources:https://impunityobserver.com/2021/06/25/how-became-haiti-republic-of-ngos/

https://reliefweb.int/report/haiti/haiti-numbers (Center for Economic and Policy Research)

A big question is whether the case of international intervention in the form of humanitarian aid in Haiti is reflective of the humanitarian aid sectors more widely. As development academics this is particularly interesting to consider in terms of long-term sustainable solutions, best usage of money, and programming with proper results, and whether some traditional approaches to intervention need to be revisited.

Humanitarian intervention, the 2010 Earthquake and NGO republic

Lessons learned from the Haiti earthquake and its legacy are still valid today. The Haitian population is discontent with the foreign intervention, and rightly so. Many basic needs are still not met, including food, shelter, education and employment. Practitioners and academics alike have studied the complex case, and such lessons may feed better future intervention and solutions.

Following the 2010 Earthquake the humanitarian and aid community flocked to Haiti and many remain on the ground to this day.

The emergency response -including relief- attracted vast amount of external investment directed at the international organisations and their activities, with little being invested into local structures. Clearly, many programs were designed for short term usage, and responding to very real emergency needs.

The flocking was massive and overcrowded, this equaled chaos. Records and data remain ambiguous with much relying on estimates despite the astronomical expenditures.

A big issue was in this chaos, basic humanitarian principles and ratified international agreements were not up-kept, money was used inefficiently and activities oftentimes overlapped, with many organisations seeking to provide their own solutions to the emergency needs.

The graduate institute of Geneva hosted an interesting debate in 2014 discussing the lessons learned during this intervention:

Key points of the debate are as follows:

- A “build back better” mantra approach was used (particularly for the western audiences) meaning, the disaster response was an opportunity to resolve previous troubles and strengthen the state – this was later criticised, with speakers in the debate highlighting the need for humanitarian community to be realistic with managing expectations (contrary to empty promises)

- Mass (unknown number, thousands) influx of aid practitioners was chaotic and uncoordinated, not in line with local -legal- regulations (such as basic registering processes, or professional vetting) and with little local involvement. An expensive cluster system was set up to coordinate. Huge amount of money was poured into the highly mediatized and funded disaster (3 billion USD from private donors, 5.3 billion USD from states, 11 billion USD promised for reconstruction)

- Shortcoming of Cholera response: 10 months after the 2010 Earthquake, NGOs began a second fundraising effort, whilst also not having capacity to respond (though only 30% of earthquake funds had been used) . Only 2 organisations -outside of the expensive coordinated cluster system- had the capacity for the emergency response (MSF and Cuban brigade) – humanitarian community was neither prepared or capable of supporting this response

- In defence of the humanitarian sector, the context was said to be difficult, with a host country that did not have the capacity

The intervention, and massive investment poured in has led to some questioning Where the money has all gone? (Journal of Haitian Studies, 2015).

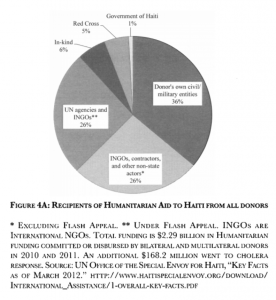

Particularly, the following graph from the above mentioned journal gives a visual understanding of the funding allocation post Earthquake 2010:

(As seen in

Highlights: lack of engagement with local government, entities and population

Persistent lack of engagement with local government, local systems (including local supply chains, practitioners, culture and, local ngos, and structures such as health) and the local population -particularly highlighted through lack of usage/understanding of local languages of French and Creole by the international community favouring English and Spanish on the ground and in their programming- not only goes against some of the basic humanitarian principles but also the ratified international agreements that acknowledge best practices in action. This is contrary to some of the basic lessons we learn in the study of development, and begs a serious question around capacity building and long term solutions.

The UN special envoy to Haiti has produced an overview surrounding donor commitments and the real investment into the Haitian state, with stark key findings:

According to the office of the Special Envoy for Haiti:

-

- Of the USD 6.43Billion disbursed by donors from 2010-2012, only 9.1 % was channeled to the Government of Haiti (and only 0.9% using PFM and procurement systems),

- Of the disbursed, only 0.6% went to local Haitian NGOs (less than half of the 1.3 % they had requested)

- Out of the top donors, only 1.4% of local procurement contracts were awarded to local companies

- This is reflected of a wider issue for “countries in fragile settings” (including Haiti): in 2010 it was found that 80% of all bi-lateral and multilateral donors bypassed national systems, with less than 3% channeled through country systems

- the report notes that the OEDC found importing food aid costs 50% more than local food purchases and 33% more than food procured in developing countries (and that local procurement creates jobs!).

- Research around the benefit of using local country systems has proven that in 82 % of cases, governments that received budget support increased spending on basic services, especially in health and education; in 100% of cases, governments’ increased the quantity of services where this was a priority in their national development plans; and in the majority of cases, using national systems for monitoring expenditure strengthens them.

Notably the report highlights that core international agreements surrounding Aid:

-

- The five principles agreed to in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness in 2005 and the Accra Agenda for Action in 2008 are:

- Ownership: Recipient countries set their own strategies for poverty reduction, improve their institutions and tackle corruption.

- Alignment: Donor countries align behind these objectives and use local systems.

- Harmonization: Donors coordinate, simplify procedures and share information to avoid duplication.

- Results: Donors and partners shift focus to development results, which get measured.

- Mutual accountability: Donors and partners are accountable for development results

- The five principles agreed to in the Paris Declaration on Aid Effectiveness in 2005 and the Accra Agenda for Action in 2008 are:

Haiti’s Development today

Clearly, there is a discord between practice and intended results in Haiti. Daniel Jean-Louis, a Haitian social entrepreneur illustrates the challenges surrounding international aid and its lack of involvement of local structure pointing towards the opportunities of considering the local country as a partner, and the very big difference between foreign aid and foreign investment.

Crucially, UNDP’s Human Development Report 2020 places Haiti in a low human development category: it is 170th out of 189 countries! Despite the concentrated international aid activities in this small nation, basic human development achievements are bellow average. The intensity of deprivation in Haiti is 48.4% (understood through multiple overlapping deprivations suffered by individuals in 3 dimensions: health, education and standard of living) (UNDP, 2020).

Root causes to local instability remain unaddressed and unconsidered in programming. Foreign responsibility for local difficulties remain unacknowledged with impunity for abusive practices.

As a development academic, considering the number games and statistics provided in this short article, these results are simply unacceptable.

Indeed, as mentioned in the Graduate Institute debate the Aid intervention may use the complex circumstances of the Haitian case as an excuse for the complications for delivering results and solutions, however understanding of the donor agreements, humanitarian law and development focused approaches shows there are wide gaps that need to be addressed in future programming. In particular surrounding the relationship between international intervenors and localities, accountability for disregard of international agreements, conventions and best practices, investing in local capacity, and ultimately considering the host country as a valid player (and leader) in its own sovereignty and long term development.

What do you think: Is the case of this Republic of NGOs a one-off or is it reflective of cracks in the global aid system more widely? Please leave your comments bellow.