Development in De Facto Authorities’ Areas

Opportunities and Challenges

Syria as a Model

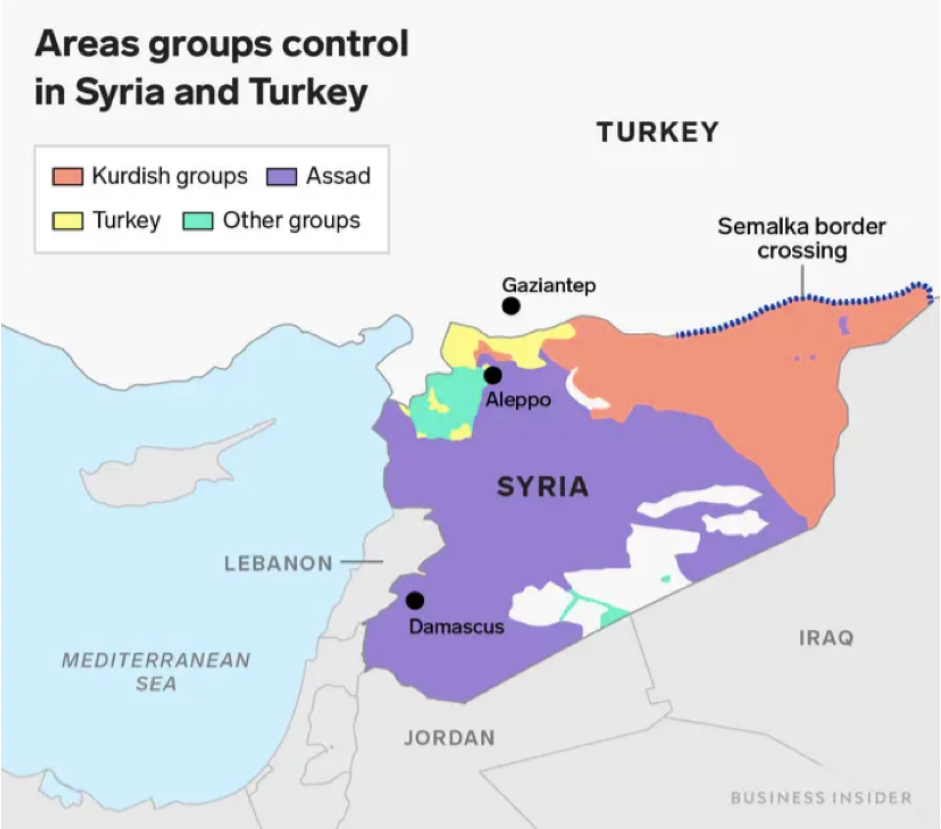

Figure 1 Syrian de facto authorities https://www.businessinsider.com/major-players-controling-territory-in-syria-as-trump-plans-withdrawal-2019-10?r=US&IR=T

Figure 1 Syrian de facto authorities https://www.businessinsider.com/major-players-controling-territory-in-syria-as-trump-plans-withdrawal-2019-10?r=US&IR=T

Donors and International organizations with their local partners might find themselves obliged to communicate with de facto authorities in order to create implementation opportunities for their policies and programs, meanwhile, several challenges might appear. I will discuss these assumptions in this article focusing on community demand-driven development approach, where variant communities live under the rule of variant Syrian de facto authorities (See Figure 1). To get a full understanding of the aforementioned topic, I’m aiming at explaining what a de facto authority is, who they are in Syria, what are their relations with the international organizations, and finally discussing the opportunities and the challenges for implementing development projects under the control of de facto authorities.

The international interfere for Development started in Syria due to the conflict that erupted in 2011 when a group of civilians protested asking the Syrian regime for a reformation and a change. This led to a civil war that is still ongoing hitherto. As a result, millions of Syrians became internal displaced persons and refugees. The international community throughout the international agencies and organisations interfered to help those civilians and to empower them for the sake of having more resilience in their own areas, accordingly, they found a lot of the Syrian territories out of the Syrian regime control, therefore, they found themselves obliged to start communications with de facto authorities that are controlling those territories. This is leading us to figure out what a de facto authority means. Houghton explains it: “The legal and regularly constituted government of a state is called a de jure government, while a de facto government is one which is actually in control of political affairs in a state or a section of a state; though it may have been set up in opposition to the de jure government” (1932, p. 177-193). It is worth mentioning in this context that there are three de facto authorities in Syria in the areas out of the Syrian regime control.

- Syrian Interim Government, (mid north of Syria).

- Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria, (eastern north of Syria).

- Syrian Salvation Government: (northern west of Syria).

The importance of local communicators:

In the Syrian conflict, communications play a crucial role in reaching a good development. The de facto authorities do not have a unified social contract (no constitution to apply), consequently, their practices are incommensurable. The international donors and organizations found it on one hand hazardous to sign development projects directly with these authorities, and on the other hand, they cannot sign agreements with the ‘de jure government’ that Assad regime represents before that international community because of the international sanctions on it. Thus, they started to search for alternatives depending on their local communicators. Ramirez and Quarry argue that good communications come from good development “It is not good communication that makes good development; it is good development that breeds good communication” (2010, p28), notwithstanding, I agree with this argumentation to a large extent. However, I think in conflicts the stress contrarily should be on the good communications that highly depend on the improvisations of the their representatives on the ground and on their relations with the de facto authorities that practice as states in all their controlled areas. Without having these local communicators to pave the way for the international organizations, there will be no development projects as the international experts are not allowed for security reasons to enter conflict areas, and on the other hand, these communicators are trusted by all parties as they are community leaders.

Effectiveness of local engagement:

In the conflicts of developing countries, communities are not only considering their ‘normal interests’, but they usually consider the de facto authorities’ policies that are ruling these communities without having any written contracts with them, therefore, their improvising policies should be met by improvising communications and implementations, in this context, McKee, Manoncourt, Yoon & Carnegie argue “an individual in a developing community enjoys less freedom to make a strictly personal decision when considering whether to adopt a new behaviour, than her/his counterpart in a developed country. In making such a decision, the individual in a developing country will consider more deeply the interests and views of her/his family, peers and community alongside her/his own preferences” (2002, Chapter 12, p2), I totally agree with this argumentation, accordingly, the capability approach might be an indispensable solution for all international organizations that interfere during conflicts, Walsham explains this approach as: “the CA focuses on the “freedom” which individuals have to lead the kinds of life they value.” (2017, p23), In this context, I had a consultative role in 2017 in analysing how NDI adopted this approach in Syria, when it conducted focus group research to gauge the perspectives and priorities of regular citizens, they argue why did they conduct this research: “Developing policy responses to these issues is essential in order to establish effective governance within Syria, both now and in a future transition process.” see here more about their project.

Challenges of implementing development in the Syrian de facto areas:

In order to describe the challenges encountered the international organizations and their donors, it would be relevant to explain why they were reluctant to deal with de facto authorities, despite the illegitimacy of the Syrian regime before its own people. However, it still represents them in international institutions such as United Nations, therefore, the regime considered that all de facto authorities are illegitimate governments, and all international interferers who are communicating with them are violating the sovereignty of the Syrian state.

The international organizations found themselves in two big dilemmas: How to help Syrians who are in need and live outside the controlled areas of the Syrian regime? And, how to avoid any legal accountability before the international laws if the regime and its allies claim that donors are breaching the state sovereignty for their communications with the de fact authorities?

As a result of that many international organizations and donors have withdrawn from dealing directly with the de facto governments and have moved towards collaborations with Syrian civil society organizations and local councils that were established by civil leaders. However, the length of the conflict has made the presence of government institutions inevitable and grand challenges appeared, such as: who will register new births? Or who will grant plates for the new cars? Who will stamp the passports of the Syrian travellers passing through the international crossing boarders? Who will register the purchase and sale of real estate? The latter question will lead us to one of the latest challenges of implementing development projects in the areas of the de facto authorities.

Legal Challenges:

The lack of a comprehensive policy and a unified framework for all actors in the development sector might be the biggest challenge for them, irrespective of the international tensions between the conflicting parties over Syria. Civil society organizations and local councils sought to create opportunities for development projects, however, they were challenged by the bureaucratic procedures such as UNOCHA Eligibility policy like due diligence and capacity assessment. Local partners cannot be contracted if they were not officially registered three years before applying for a grant in addition to the requirement of having a bank account and this led to deprive many organizations that found themselves compelled to operate in the areas of the de facto authorities as there are no banks in the de facto authorities’ areas and they do not comply the three years condition.

Furthermore, the emerging de facto authorities were not able to organize themselves quickly enough to initiate ministries and offices to register new organizations, and at the same time these organizations are considered by the ‘de jure government’ illegitimate and cannot be registered as organizations, therefore the needs and demands of the people remain on the one hand under the bureaucratic anvil of international policies and on the other hand under the hammer of the de-facto authorities’ inability to meet the acceleration of events and the daily increasing needs.

HLP challenges in Syria:

Housing, Lands, and properties rights file was a catalyst for an intervention of many international organizations to initiate projects aim at preserving the rights of HLP owners. This challenge was clearly noticed after issuing Law No. 10 by the Syrian regime, this law allows the confiscation of the properties of Syrian refugees and internally displaced persons who cannot claim their ownership for their properties in a short deadline, especially, the majority of HLP documents were burned or lost in the war.

A lot of development projects to be implemented need lands to build the projects on them, the landlords might be refugees, or IDPS, accordingly, the de facto authorities cannot rent out these lands within the absence of their owners because the ‘de jure government’ is the only party that have the national cadastral, meanwhile, the regime was adopting a methodological process of confiscating the lands of all absents and then to rent them out for others. It is worth mentioning that the Syrians who had been recognized as refugees according to 1951 convention could not go to the Syrian embassies to send a power of attorney for lawyers in Syria to claim their ownership of their properties; otherwise, they will lose their rights of asylum.

Political Challenges:

The majority of the international organizations coordinate their projects in northern Syria through UNOCHA office that is stationed in Gaziantep in southern Turkey, therefore, all international humanitarian aids must pass to the north of Syria throughout the Turkish boarders, it would be after getting an annual approval of the UN security council, this approval sometimes need to go through a compromising deal with Russia and China as they are allays of the Syrian regime, and they want the aid to pass to the civilians who live in the de facto authorities only through Damascus Government Route. The challenges of this bureaucratic process is not only leading to diverting aid by the regime military, as this article shows, but also, it is not a community demand-driven, as it is widely known that the civilians fled the regime areas towards freedom. Accordingly the UN stated, “The United Nations will continue to do its part to assure the Council that aid to all parts of the Syrian Arab Republic is delivered, based firmly on needs, without discrimination and in line with humanitarian principles” (p.9, 2020) It could be argued that this statement clearly lacks a community demand-driven to express a comprehensive impartiality as one of the main humanitarian principles, as it is not defined the needs of whom? Especially when we know that each power claims that it knows the real needs of the Syrians.

Opportunities of implementing development in the Syrian de facto areas:

In the absence of the ‘de jure government’ and its inability to govern its whole territories, de facto authorities arose in Syria, in conjunction with the presence of the international community will to help 13.4 million Syrian civilians who are in need, 6.7 of them are IDPs according to UNHCR report, they are living in the three abovementioned de facto authorities. Each of these de facto authorities is affiliated with an international power, and each community lives under the control of these authorities has their own humanitarian and development needs, and all these new established authorities suffer from the lack of income and they are in need for international funds to survive, therefore they are all try to have flexible procedures when it comes to deal with international organizations.

Moreover, there are several development projects that are implemented directly by international organizations; I was managing one of these projects at the end of 2018, which unfortunately, didn’t survive after the withdrawn of the donors. It would seem this failure happened due to two essential reasons, the first one is the transnational political affiliations among the struggling powers on the ground, specifically, when the Syrian Salvation Government that is affiliated with Alnusra Front has controlled some areas from the Syrian Interim Government where we were running our projects, accordingly, a decision was made by the international donors to cut the funds and stop the project abruptly, notwithstanding, they have themselves refused previously to accept a community demand-driven development approach where the local stakeholders gathered and appealed them several times to get some fees for the services they provide at these governmental centres under the pretext they do not want the people to accustom to free of charge services, hence, they will lose the only income that might cover the running costs of these centres if the donors disappear.

Unfortunately, the local communities were the most affected and lost big opportunities of the continuity of the success of their long-term development projects because the donor countries stopped the funds for their inability to ensure that funds will not reach the de-facto authorities. On the other hand, organizations such as GIZ reinstated its funds for the health sector in the salvation government areas as this article shows.

Can we Turn Challenges into opportunities?

Local councils were established by direct elections of the local communities after the disappearance of the ‘de jure government’ institutions, concurrently, the international organizations have been trying to avoid falling into the abovementioned moral and legal dilemmas, therefore they found the challenge of the absence of the ‘de jure government’ is turning into an opportunity when these local councils established.

It was discussed above that some organizations don’t meet some donors’ requirements such as the three years and the bank account conditions, apparently, these NGOs were able to turn the challenge of the three years into an opportunity after they signed partnerships agreements with organizations that fulfilled these conditions, the first registered party might be stationed in Turkey, and the second party (the implementer) is stationed in a de facto authority area.

Another challenge can be turned into an opportunity if there is a political will at governments mainly EU governments specifically when it comes to HLP file which it is used by the Syrian regime to prevent the return of refugees from Europe and neighbouring countries like Turkey and Jordan. It might be through allowing the Syrians to visit the Consulates to get documents that would help them to approve their ownerships of their properties, still it is very sensitive, taking into consideration the possibility of using these amendments by the regime to get normalization and to get rid of the sanctions imposed on it by the international community.

To conclude, it was very challenging for all international organizations to communicate with de facto authorities, however, a lot of INGOs depended on local community leaders as communicators to pave the way for them to implement their projects, they depended on approaches that engage locals. Ramirez and Quarry argues that “Another Development called for helping people improve their lives in their own terms. Intrinsic to this, it is simply not possible to implement this approach to development without enhanced communication between all involved in the process”. (2010, p29 -30).

Reflections on my personal experience of blogging about development

As a development practitioner for more than ten years, I found this experience as a place to think freely and an opportunity to reflect on my personal experience during the last decade, I thought deeply about the pros and cons that went through during the implementation of development projects and I have tried to frame them as lessons learned.

Continuous work in development projects on the ground without a short break for a reflection will stop the process of self-development, which is highly needed to keep an ongoing success for any long-term project. The experiment was an opportunity to shed light on the catastrophic consequences that international organizations may have for their rapid intervention in conflicts areas without an assessment that is based on a community demand driven approach and without a comprehensive understanding for the local contexts. I am grateful for this experience that froze for a while the hectic daily events that I live along the Syrian conflict, in addition to learn about new topics discussed by my group colleagues, and other groups specially the ones we reflected on them. I reached to a conclusion, if we don’t create our own spaces to reflect, then, we will be turning into operational tools, in a nutshell, I can say that blogs are simple and friendly spaces that could lead to fruitful impacts on individual as practitioners and on organizations that seek to develop its upcoming development projects. In this context, I would agree with Denskus and Papan when they say: “Development blogging does not need a designated space, special training, workshops, or degrees, enabling dialogues between those with varying levels of development knowledge and experience, and working in different roles, for example volunteers, academics, and practitioners.” (2013, p464).

References:

- Geoff Walsham (2017) ICT4D research: reflections on history and future agenda, Information Technology for Development, 23:1, 18-41, DOI: 10.1080/02681102.2016.1246406

- Ricardo Ramírez & Wendy Quarry, 2010. “Communication for Another Development,” Development, Palgrave Macmillan;Society for International Deveopment, vol. 53

- THE NATURE AND GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF RECOGNITION OF DE FACTO GOVERNMENTS Author(s): N. D. HOUGHTON Source: The Southwestern Social Science Quarterly , SEPTEMBER, 1932, Vol. 13, No. 2 (SEPTEMBER, 1932), pp. 177-193 Published by: Wiley Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42864794

- Tobias Denskus & Andrea S. Papan (2013): Reflexive engagements: the international development blogging evolution and its challenges, Development in Practice, 23:4, 455-467.

Links:

- http://web.worldbank.org/archive/website01541/WEB/0__CO-48.HTM

- https://syriadirect.org/after-cuts-german-aid-agency-reinstates-funding-to-health-directorates-in-rebel-held-north-with-strict-conditions/

- https://www.ndi.org/our-stories/bridging-gap-syrians-work-policymakers-shape-their-communities

- Review of United Nations humanitarian cross-line and cross-border operations – Report of the Secretary-General (S/2020/401) https://reliefweb.int/report/syrian-arab-republic/review-united-nations-humanitarian-cross-line-and-cross-border]