As I have teased in my previous blog post, I will critically examine a highly publicised (and later, much criticised) series of news reports and media content around the case of Anna* – a 13-year old girl of African origin who disappeared for 9 months in Sweden. The case will be examined through the application of Chouliaraki’s concept of ‘Post-Humanitarianism’, the two related concepts of ‘Digital [and] Everyday Humanitarianism’, and the ‘Digital Saviour Complex’ – in order to reflect on the logic underpinning the various forms of publication(s).

As detailed in a much publicised airing of the radio programme “Medierna”, broadcast on 15 October 2021, the case of Anna become widely known in Sweden in February 2021 as Expressen, one of Sweden’s largest newspapers, published her actual name (i.e. not Anna) and the story of how she had gone missing. At that time, Expressen reported that Anna had run away prior to a monitored visit with her biological parents from whom she and 7 siblings had been separated from by social services following reports of violence in the home. Anna is reportedly unhappy with the social services and want to stay with her parents. What is notable is that despite the complicated and sensitive nature of the case, and with no other newspaper initially reporting the name or picture of the missing child, Expressen did post the name and picture of Anna from the onset, even prior to the police doing so. Shortly thereafter, Expressen and their freelance reporter – Alexandra Pascalidou – posted damning criticism from the family of Anna who claim that the police and authorities were not acting the way they should because the family and Anna are of African origin. The police were not invited to comment on those allegations, and in social media the reporter insinuated that the reason Anna remained missing was because of the police and public not caring because she was an immigrant of African origin.

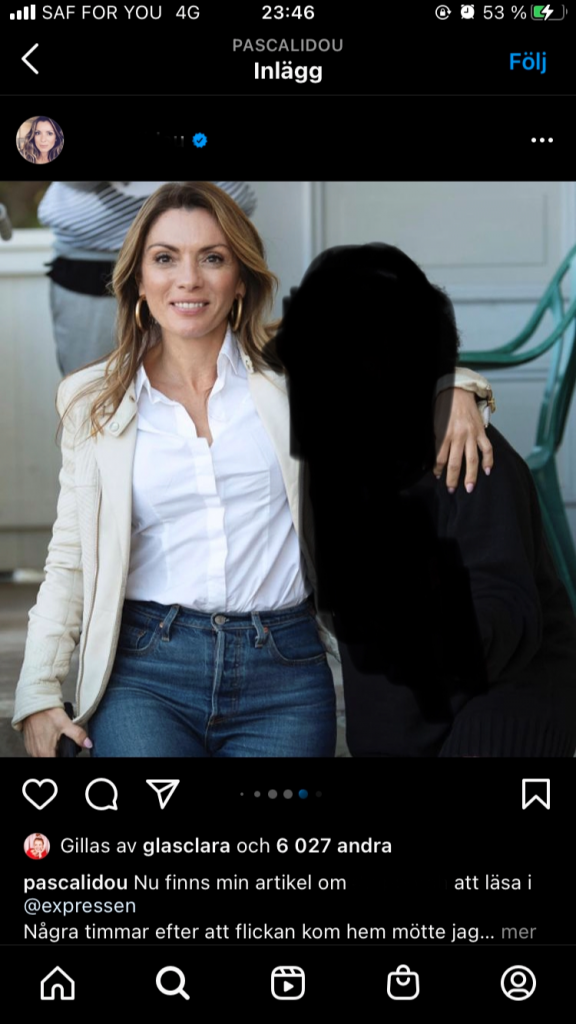

After being missing for 9 months, in October 2021, Anna returned home to her parents’ house. Upon her return home, Expressen and their freelance reporter – Alexandra Pascalidou – visited the house to conduct interviews, take photos and videos, and later posted all of these on their news site without yet again censoring the names or faces of Anna or the family. Simultaneously, the reporter posted similar content on her own social media channels, including a hashtag with Anna’s name and several photos with the reporter seemingly imposing herself in the photos with Anna and the other family members. The publication of Anna’s return on the news site of Expressen, as well as the Instagram account of the reporter, received much backlash on social media and other news outlets. After initially defending their publication, the criticism eventually prompted Expressen to reconsider their position and therefore Expressen later removed all explicit mentions of Anna and all photos and videos of her return.

In addition to the complicated ethical dilemmas and journalism standards around publishing sensitive information about an underage girl having gone missing, and later having returned home, what makes this case especially interesting in terms of communication for development and communicating for social change is the continued behaviour of the freelance reporter from Expressen – Alexandra Pascalidou. Her response to the criticism levied against the reporting by Expressen as well as her personal use of photos and videos of Anna and her family on her personal social media channels (primarily Instagram), was that she was standing up for the rights of the child to be heard and for a vulnerable child. She initially refused to participate in the initial radio programme, but was later interviewed for the same radio programme on 23rd October.

If you are a Swedish speaker, you can listen to the first 11,5 minutes of the programme below.

In this interview, she defends the Expressen publication with her wanting to highlight and amplify the voice of Anna and her family, despite the ethical dilemma in publicizing such sensitive information about a vulnerable 13-year old and her family’s pending case and interactions with social services. Furthermore, the reporter says that it is ultimately the responsibility of the Editor-in-Chief at Expressen to decide on such publishing dilemmas and to approve the story and the level of confidentiality, including the choice of pictures that were published. She claims to merely be a freelance reporter with little influence over the direction of the story or the confidentiality level. However, and as is pointed out by the radio programme host, the reporter has posted those exact photos on her personal (publicly open) Instagram account that has 37,000 followers to date. While questioning the reporter why she has still not unpublished those posts (i.e. images, name, hashtag and details of Anna) from her own Instagram account, the reporter turns defensive and claims that the work is being unfairly criticized because she is giving voice to a traumatized and vulnerable child who want to speak out, and that she has received a lot of hate towards her and not only constructive criticism.

Similarly to the critique raised by the radio host, I would also like to question the choice of photos uploaded on the reporter’s Instagram account and her decision to keep them published together with the name of the Anna* on an open Instagram account. The reporter explicitly raises concerns that the reporter is using this child to strengthen her personal brand as a reporter and social media personality, to which the reporter somewhat angrily responds that she has no interest in doing. The reporter’s only interest is to give a microphone to this vulnerable child. However, as you can see on the below images (redacted by myself for protecting the integrity of Anna), the choice of photos for the story of how Anna has returned are questionable from both an ethics standpoint within the field of journalism, but also with the concept of the ‘Digital Saviour Complex’ and ‘Post-Humanitarianism’ in mind. The reason for why the reporter is posing together with Anna and a few of her siblings is not clear and serves perhaps, as suggested, no other purpose than to strengthen the personal brand and status of the reporter as a ‘saviour’/champion of this child.

As argued by Richey (2018), the new forms of ‘everyday humanitarianism’ seem to be present in the logic used by the reporter in explaining and defending her publication of the above photos. The reporter, through her publications on Expressen and her personal Instagram account, is giving voice to a vulnerable child. The reporter portrays herself and her actions, including something as mundane as creating a hashtag with Anna’s name and sharing of her photos, and publishing her sensitive story (without appearing to actually critically investigate whether the allegations of violence in the home are true) as her way of challenging the ‘establishment’. In this portrayal, the reporter does indeed appear to ‘congratulate herself’ on a job well done in fighting for the vulnerable and suffering Anna and for continuously fighting “the power” on behalf of vulnerable others.

To conclude, I would argue that the decision by the reporter to not remove the photos and names of Anna and her family from the reporter’s personal Instagram account, her decision to insert herself in these photos, and the reporter’s statements in defending her current stance, are indications that she is under the spell of the ‘Digital Saviour Complex’ and that she operates within the self-congratulatory and self-gratifying logic of ‘Post-Humanitarianism’.

* Note that Anna in reality is called something else.

References:

- Shringarpure, B. (2020). Africa and the Digital Savior Complex. Journal of African Cultural Studies, 32:2, 178-194.

- Sveriges Radio (2021). Extremt närgånget i Expressen om utsatt barn och var drar SVT gränsen för fejk i naturfilm?

- Sveriges Radio (2021). Pascalidou slår tillbaka, medial hysteri om Squid Game-lekar och NWT dubbelt klandrade för våldtäktsrapportering.

- Richey, L.A. (2018). Conceptualizing “Everyday Humanitarianism”: Ethics, Affects, and Practices of Contemporary Global Helping, New Political Science, 40:4, 625-639