Introduction

Introduction

Information and communication technology for development (ICT4D) is a relatively new term that describes the academic field focussing on the use of ICTs in the realm of international development. However, examining the label ICT4D can already be dated back to “(…) the mid-1980s, at least in terms of substantial amounts of formal research published in refereed journals or conferences” (Walsham 2017: 19).

Thus, researchers have already worked for some time on the issue. Nevertheless, the overall discussion received a new impetus when digitalization became part of the development rational, and the term “digital development” was coined. In a post on his blog Appropriating Technology, Roberts (2019) suggests using it as a collective term, including three different sub terms: “Digital in Development”, “Digital for Development” and “Development in a Digital World”.

With digital in development, he refers to the use of ICTs by development agencies to make their internal workflows more efficient. Digital for development then again means the explicit elaboration and implementation of digital tools to create outcomes for and impacts on development. Finally, development in a digital world is a more general term for international development in a more and more digitalised environment (ibid.).

In this blog post, I will use the term digital for development to describe the application of digital means in international negotiation settings. With this, I will illustrate that in order to empower marginalised or vulnerable groups to inform themselves about peace processes and to provide opportunities and resources for their participation, both traditional as well as digital means are necessary – a “hybrid” form of peacebuilding.

A national dialogue scenario

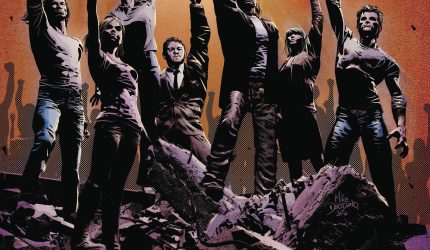

The website digitalpeacemaking.com provides a scenario that works as the basis for my analysis. Basically, it is about a political transition phase in a fictional state in forms of a national dialogue process after a popular uprising. It describes, on the one hand, digital inclusion options for its support and, on the other hand, contrasts them with classical ways of peacebuilding.

In brief, in the scenario broad public protests, and long-lasting political mobilisation made the authoritarian national government of an imaginary country resign and gave way for democratic reforms, initiated by a provisional military council. After rising pressure from the international community, the council agreed to foster the transition process through a national dialogue conference with representatives from all social, economic, and political groups, flanked by consultations involving the whole population (Digital Peacemaking 2019).

To prepare the process, several leadership bodies were established, and the overall programme was elaborated. Then followed the main dialogue process, which involved a combination of plenary sessions, working groups and specialised consultations, leading to a national dialogue conference followed by an implementation process (ibid.).

This scenario represents a truly participatory development, as it intends an “informed consent [as] the cornerstone of ethical practice (…)” as well as a real dialogue involving all the citizens of the country with respect to the consultation process – in contrast for example to the usual form-filling during democratic elections (Ademolu and Warrington 2019: 375).

On the one hand, several digital means were applied during the preparation of the negotiations, which deepened its participatory character:

- Setting-up a website and initiating videoconferences to promote online collaboration and virtual exchange between the different parties of the process.

- Using social media channels to start a public participatory peace campaign sharing multimedia content.

- Public digital consultations through online discussion fora.

- Virtual public quick polls using online forms, polling apps, messaging services and SMS systems.

Furthermore, widespread misinformation among the population about the negotiations was contested using apps, SMS systems and social media analysis tools (Digital Peacemaking 2019). All these measures can be classified as “participatory ICT4D (…) focused on a specific technology as a subject of design, or on a development objective enabled by ICT (…) [with] practical or emancipatory objectives, which attempt to empower and protect poor and marginalized populations” (Bentley et al. 2019: 478).

On the other hand, more traditional ways of peacebuilding were implied to allow the representatives from all social, economic, and political groups to prepare for the national dialogue conference that included:

- Informal talks to recognise each other’s positions, interests and needs.

- Consultations behind closed doors to resolve dissents.

- Workshops to elaborate the dialogue structure and set the agenda.

Additionally, parallelly to the participatory online measures mentioned above, public referenda were held to legitimise the results of the process, accompanied by constitutional and legal reform bodies to monitor the implementation process as well as truth and reconciliation commissions to come to terms with the conflicts of the past (Digital Peacemaking 2019).

One could argue that digital initiatives in general save time and money as they merely take place virtually and, thus, reduce the organizational and financial efforts for meetings and travelling to a minimum. However, a crucial element of the peace process can only be achieved rudimentarily by online means: To build trust among the different parties involved.

That is why, to foster development in forms of a transformational peace process, human relationships are needed that stand at the core of any confidence-building. This leads me to the question whether the use of ICTs leads to development in general and, if yes, how this happens.

Development in a virtual world

Sein, Thapa, Hatakka and Sæbø (2019) suggest that “there is a knowledge gap in the link between ICT intervention and development in the context of developing countries” (p. 8). Any transformative process, they argue, needs human development achieved by collective action of the central actors setting up social networks based on the creation of social capital (ibid.: 18). Hence, this “increased social interaction can promote the trust, acceptance, and alignment that are necessary for action in a community” (ibid.: 14).

Of course, like in the scenario above, the effect of this “construction of human solidarity” could be enlarged using social media to make so-called laptop humanitarians care about the suffering of others from the comfort of their homes and act or vote accordingly. Yet, “(…) mass mobilization of ‘everyday humanitarians’ by means of smartphones and laptops may lend further legitimacy to the political actions (…) but fail to foster a meaningful and effective transnational solidarity” (Richey 2018: 637).

Even worse, if these factors are not considered accordingly, the imperative use of ICTs in political transformation processes of development holds the danger of fostering structures of “digital colonialism”, when using “digital technology for political, economic and social domination of another nation or territory” (Kwet 2021). Hence, if the dominant powers are equivalent to the owners of the digital infrastructure, they might use their knowledge and control of the means of computation to keep other social groups in a situation of permanent dependency.

Additionally, “(…) if ICTs are to reach their full potential as a force for change, a feminist and social justice approach is needed” (O’Donnell and Sweetman 2018: 217), as different forms of identities – including gender, race, and class – are all limiting factors with respect to access to the digital sphere in each particular context. For example, recent data show that women are ten per cent less likely than men to own a mobile phone on a global scale. This gender gap is even higher in some regions of the world: In South Asia, their number sums up to 26 per cent, and 70 per cent of them are less likely to go on the internet (ibid.: 219).

That is why, one of the first steps to consider before applying ICTs to development dynamics like for example implementing the outcomes of a national dialogue process in the scenario described above is the provision of cheap and fast internet connectivity to enable marginalised and vulnerable groups to be part of it, making it more inclusive and beneficial for all (Pepper and Jackman 2019: 29).

Maybe ironically, the reality speaks a different language as the majority of the people and communities that could benefit most from connectivity are currently least connected and live in the developing world. It is sad to say, but “if we continue on this trajectory, connectivity may never reach those whose lives it can transform the most” (ibid.: 31).

Conclusion

Using the digital for development by applying ICTs to international negotiation settings has the potential to include marginalised or vulnerable groups into peace processes by keeping them informed and enhance their participation. However, apart from digital also traditional means are necessary to achieve this goal, as they are necessary to build trust, acceptance, and alignment through collective social interaction that represents the foundation of any peacebuilding process.

Using social media may enhance peace processes but holds the danger of fostering structures of “digital colonialism” if the ownership of the digital infrastructure remains in the hands of a few and, hence, keeps other social groups technologically dependent to get access to the digital sphere. This is especially true when it comes to marginalised and vulnerable groups, including limiting factors like gender, race, and class. Cheap and fast internet connectivity everywhere might be a way to tackle these limitations but is still far from reality in many parts of the developing world.

For this reason, finding the right combination of digital and traditional measures – a “hybrid” form of peacebuilding – might be a challenging but promising way for that matter. The perfect mixture will always depend on the specific context, which makes a preliminary analysis of the local conditions a sine qua non for any research in this regard.

Concluding reflections on the blogging exercise

Since I moved to Bolivia with my family in February 2018, one of my assigned private duties was writing the weekly entries of our family blog. Hence, I was already somehow accustomed to the exercise of designing and writing a blog, although with a rather personal and informal touch. Nevertheless, being assigned to a working group within the realm of a university course with the task to set up and keep running an academic blog on a scientific theme represented a challenge to me, for several reasons.

First of all, I was put in an intergenerational team together with four fellow students of mine with multidisciplinary backgrounds, who were total strangers to me as I neither met them beforehand nor worked with them professionally. Bearing this in mind, I was quite sceptical about the task to create a common outcome in form of a blog, as each one of us would bring his or her individual workflow into the process.

Out of my professional experience, I knew that this would be quite an ambitious task, especially in a grassroots democratically organised group like ours. Yet, I learned from the exercise that through collaboration, peer feedback, and the distribution of duties achieving a shared goal is possible, even under the circumstances described above.

Secondly, my blog entries fit into my academic writing practices as they deal with the topic of digital peacebuilding as part of communication for development, which I consider focussing on thematically in my Master Thesis next year. Still, I became aware once more after working as a multimedia editor for several years that the writing style in the online (blogging) world is totally distinct from the classical academic one.

Last, but not least, as we also shared our blog posts on social media, I also hoped to contribute with my writing to “strengthening connections and discussions thereby creating a global understanding of ‘development’” (Denskus 2019). However, I am very aware that even though our blog featured a topic with a global scope, its content was merely read by professionals or university students already connected to the field and discussions with respect to development issues, which limited the outreach of our work to the members of this small global elite.

Literature:

- Ademolu, E. & Warrington, S. (2019): Who Gets to Talk About NGO Images of Global Poverty?, Photography and Culture, August

- Bentley, C.M., Nemer, D. & Vannini, S. (2019): “When words become unclear”: unmasking ICT through visual methodologies in participatory ICT4D, AI & Society, Vol. 34, pp. 477–493

- Denskus, T. (2019): Blogging and curating content as strategies to diversify discussions and communicate development differently, Aidnography (online blog), December 17 (https://aidnography.blogspot.com/2019/12/blogging-curating-globaldev-content-diversify-communicate-development-differently.html)

- Digital Peacemaking (2019), National Dialogue process after a popular uprising. Digital Inclusion in Peacemaking, digitalpeacemaking.com (website), https://digitalpeacemaking.com/s/national-dialogue

- Kwet, M. (2021): Digital colonialism: the evolution of American empire, ROAR (online magazine), March 3 (https://roarmag.org/essays/digital-colonialism-the-evolution-of-american-empire/)

- O’Donnell, A. & Sweetman, C.(2018): Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs, Gender & Development, 26:2, pp. 217-229

- Pepper, Robert & Jackman, Molly (2019): A Data-Driven Approach to Closing the Internet Inclusion Gap, in: Graham, M. (ed.): Digital Economies at Global Margins, Ottawa, ON/Boston, MA: IDRC/MIT Press, pp. 29-32

- Richey, L.-A. (2018): Conceptualizing “Everyday Humanitarianism”: Ethics, Affects, and Practices of Contemporary Global Helping, New Political Science, Vol. 40:4, pp. 625-639

- Roberts, T. (2019): Digital Development: what’s in a name?, Appropriating Technology (online blog), August 9 (http://www.appropriatingtechnology.org/?q=node/302)

- Sein, M.K., Thapa, D, Hatakka, M. & Sæbø, Ø.(2019): A holistic perspective on the theoretical foundations for ICT4D research, Information Technology for Development, 25:1, pp. 7-25

- Walsham, G.(2017): ICT4D research: reflections on history and future agenda, Information Technology for Development, 23:1, pp. 18-41