Developing Images in Digital Times

A picture is worth a thousand words.

Not surprisingly, the aphorism above is common in multiple languages. Images can carry very strong messages, and they tell powerful stories. Pictures have a heavy presence in communication for development. For this reason in this blog, Developing Narratives in Digital Times, there is a specific category dedicated to visual imagery, Pictures vs storyline. Overall, the blog gathers thoughts and impressions about Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D), and the role of communication in the aid industry.

New technologies and new media have “brought about yet another paradigmatic and epistemic shift in the communication of solidarity” (Shringarpure, B. 2020: 179). On one hand, they are great tools for new perspectives, participatory methods and new narratives. On the other hand, they might reinforce some existing inequalities between Global North and the Global South, the dominant Western society and the more vulnerable populations.

The blog shares a postcolonial vision of the development for all the different subfields of ICT4D. The perseverance of a distinction between ‘us’, the Global North, developed, proactive, and wealthy; and the ‘other’, the Global South, poor, corrupted, helpless, and in need of salvation. This vision is an heritage of colonialism that is not easy to eradicate. New ICT4D strategies could be the chance to change to social justice and global equality. In order to do so, the Global North should develop new narratives and adopt new methods for development.

What is the role of pictures in the ICT4D? How are images involved in social change?

This essay is an attempt to answer the two questions above. The topic is very broad and touches on many aspects and actors of the aid industry, such as stereotypes, social media presence, the white savior complex, poverty porn, fundraising campaigns. compassion fatigue, inclusive photography and participatory methods. None of these terms is new for someone familiar with the humanitarian aid jargon. Furthermore, all the terms/aspects mentioned above fall under the umbrella of the Western hegemonic postcolonial vision.

The colonial West, through different practices of representation, managed to create and produce racial discourses. Part of this colonial discourse is the way the Global South is symbolically classified as inferior compared to the Western society. All the elements of representations relate in a complex system of power relations, where power should not be considered “only in terms of economic exploitation and physical coercion, but also in broader cultural or symbolic terms, including the power to represent someone or something in a certain way” (Hall, S., Evans, J. and Nixon, S., ed. 2013: 249-250).

The essay is divided in four different paragraphs: ‘Stereotypes Harm Dignity’; Social media, a showcase for white saviors or a tool for social change?; Can poverty porn still be justified for fundraising campaigns?; #InclusivePhotography. Starting the discussion on stereotypes is key as stereotyping holds up existing colonial hierarchies (2013). Stereotypes are heavily present in two debates of communication for development such as the white savior complex, and poverty porn. These two aspects are analyzed respectively in the second and the third paragraph. There are different actors involved in stereotypical representation, individual actors, private social media accounts or public figures, and then institutions and organizations, which play an important role in the development industry. In this essay, the second paragraph focuses on the individual actors such as volunteers or tourists and their behavior on social media accounts. The third paragraph focuses on the use of pictures by NGOs, international organizations, etc. Last, the fourth paragraph puts a light on the responses and initiatives moving towards images that are more inclusive and dignifying for all.

‘Stereotypes Harm Dignity’

‘Stereotypes Harm Dignity’ is one of the messages of the awareness campaign Radi-Aid, also mentioned in the blog post Would you volunteer if you couldn’t share pictures on social media?. Created by the Norwegian Students’ and Academics’ Assistance Fund (SAIH), the campaign has the objective to bring down stereotypes and oversimplified narrations. The humanitarian representation is a collection of stereotypical images. For example, portraits of black Africans in poor conditions, without access to basic needs, such as electricity, food, and also services such as education and health care. Even if it can be a fact that some communities in some parts of the world lack basic needs and services, a stereotypical representation can be harmful.

For Stuart Hall stereotypes reduce to a few essentials “simple, vivid, memorable, easily grasping and widely recognized characteristics”. Hall also features stereotyping as a practice of “closure and exclusion”, classifying the ‘other’ with fixed ‘differences’. Therefore, belonging to the “other” is a condition that cannot be changed. In these terms reinforcing a stereotype not only does not contribute to social change, it actually maintains “social and symbolic order” (Hall, S., Evans, J. and Nixon, S., ed. 2013: 247-248). Stereotyping is counterproductive for the development fields. It plays a negative impact in all the discourses about social equality and justice.

The differences mentioned by Hall are sets of “binary oppositions”, white/black, civilization/savagery, etc. (2013: 232). During colonial times, the differences were polarized by visual discourses. The representations of human bodies and other physical characteristics lead racial discourses to extremes. “The body itself and its differences were visible for all to see” (2013: 233). This is how the differences were perceived as fixed by nature. The representation of fixed differences contributed to create the concept of the ‘others’ for any non-western society.

Social media, a showcase for white saviors or a tool for social change?

We, as human beings, have always been “keen to give off good impressions to others” even before social media (Pooley, J. 2021). We live in a social sphere where we look for recognition, namely we need our mates’ approval (James, W.,1892). In the digital era the social sphere moved from the real world to the virtual one. We live in a world where social media represents “a platform for staging an idealized self-presentation” (Schwarz, K. & Richey, L.-A., 2019: 1930), and recognition comes in the form of likes, shares, comments.

The self-presentation is often a very self-centered narration, where the main character is at the center of the attention and other people in the scene are in “the background, anonymous persons playing supporting roles” (Gordon G., 2012: 92). In the white savior portraits, we witness many self-centered representations, where the Western subjects “prioritize looking cool and having an adventure over understanding the consequences” of what they are doing (2012: 93). An example for the white savior stereotypical representation is the video from Comic Relief with the famous singer Ed Sheeran, who, while visiting Liberia offers to pay hotel costs for street children “Ed Sheeran has good intentions,”(…) “But the problem is the video is focused on Ed Sheeran as the main character. He is portrayed as the only one coming down and being able to help.” (The Guardian cited in Denskus, T., 2019).

Even if it is still highly probable to bump into white savior images on social media, it is also true that activists or new initiatives committed to social change can now get visibility and large consents from the general public through digital platforms. In spite of everything, social networks are also a site to share media text, gather information, create and sustain social conventions (Schwarz, K. & Richey, L.-A., 2019: 1929-1930).

Can poverty porn still be justified for fundraising campaigns?

The already mentioned Sheeran-fronted Comic Relief video is also a good example of what poverty porn is. The video shows vulnerable young boys sleeping on the streets and at the end of the video, the link for donations appears. These sorts of shock effect campaigns that generate pity on the public opinion are somehow outdated nowadays. Nevertheless, poverty porn is still used by NGOs and other organizations that rely on private donations to sustain their projects and themselves. Extensive experience and research reveals that for NGOs, shock effect campaigns are still the most effective at raising funds, particularly for urgent humanitarian appeals (Scott, M., 2014: 145).

Poverty porn has several aspects that negatively impact social development. For example, the problems faced by the people in the Global South appear oversimplified: Global South/poverty, donation/solution. Furthermore, shock effect campaigns act upon emotions, without giving a full picture, and don’t urge for long-term solution. Also, as mentioned before, poverty porn reinforces negative stereotypes through discourses that create an “othering” effect and gloss over critical local context. Poverty porn is a representation created by and targeting only people in the Global North, using faces and situations belonging to the Global South.

It should be in the rights of people portrayed in humanitarian campaigns to be involved in the process of images creations or at least to have a say about the result before it gets published. This practice has not been considered for many years (Ademolu, E. & Warrington, S., 2019). According to Ademolu and Warrington, people in the Global South have different concerns about images of poverty and suffering, some of them are offended and dislike these representations. Moreover, shock effect photos do not give a full picture of the real situation. People in the Global South understand that images of suffering are more effective to raise donations. At the same time, “they wanted the viewers to also see their community members helping one another, to show resilience as well as need, and solutions as well as problems” (2019: 371).

#InclusivePhotography

Social media is often a site for criticism. “Socially unacceptable ways of representing the African “other” and the humanitarian self” are often denigrated by several accounts, such as No White Saviors, Barbie Savior, or Humanitarians of Tinder (Schwarz, K. & Richey, L.-A., 2019: 1936). Data suggest that critical activism on social media affects how humanitarians post about their experiences (2019: 1938). Nevertheless, even if this impact could be considered a positive result, critics alone do not provide solutions. For instance, to stop posting is not a solution. Social networks have the potential to spread voices and create communities. They also work as a source of inspiration, encouraging social actions.

Thus, this paragraph aims to provide inspirational readings on visual productions using online sources. There are many initiatives with the objective to change the paradigm of visual representations. In the blog post Rethinking Images I already mentioned the projects: Regarding Humanity, The Authority Collective, The Everyday Projects, Native and Diversify Photo. In addition to online sources there are also live events or conversations happening on social media, #InclusivePhography is one of them. It was a Q&A session organized on Twitter by BRIGHT Magazine and The Everyday Project. All these projects have a shared ethic of photography. The common ground is to promote diversity, and use the power of images to challenge inequalities and stereotypes.

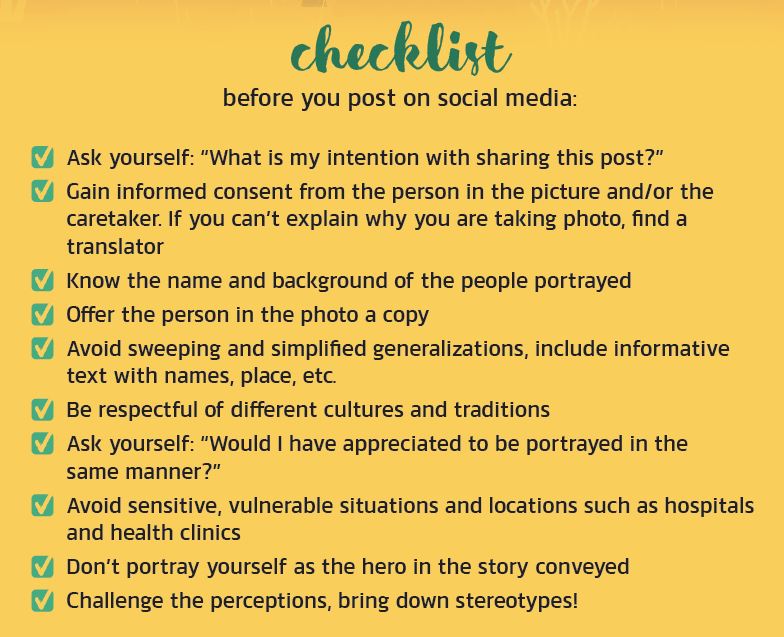

For instance, Radi-Aid and Barbie Savior propose the “social media guide” targeting volunteers and travelers. It is based on four principles:

- Promote dignity,

- Gain informed consent,

- Question your intentions,

- Use your chance – bring down stereotypes.

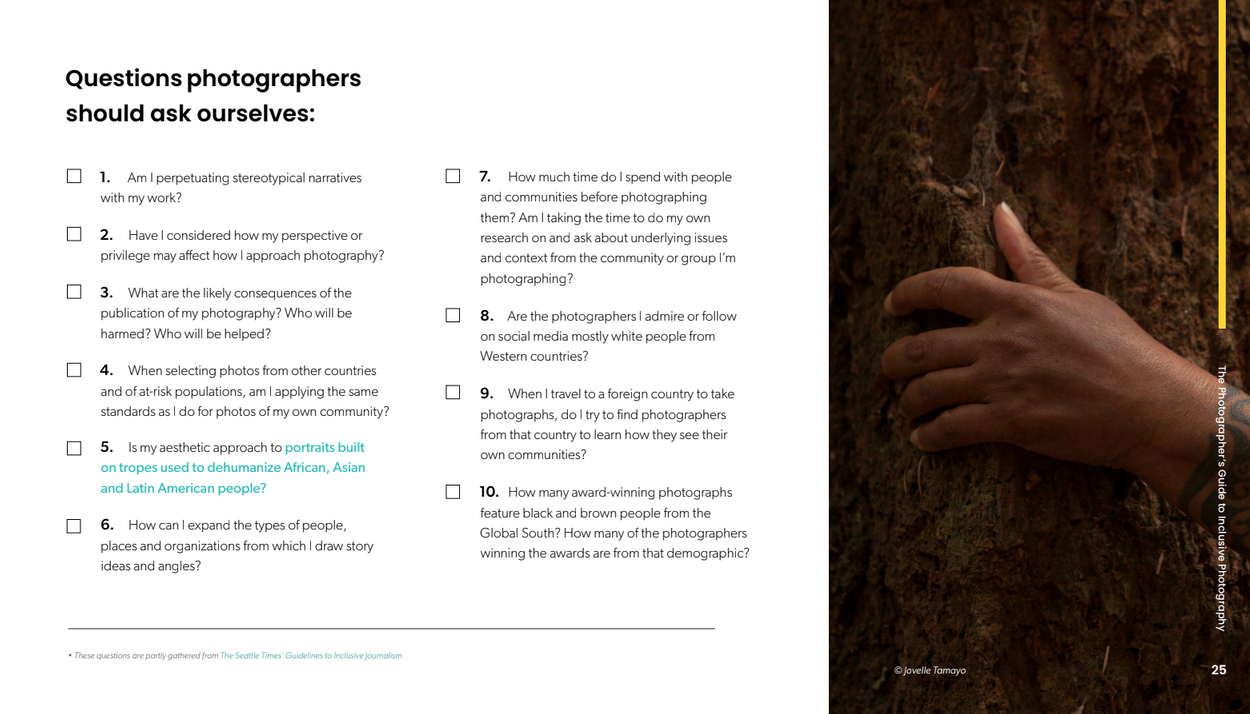

Similarly, The Authority Collective proposes The Photographer’s Guide to Inclusive Photography, which aims to help photographers to focus more on the story, namely the context of the community that is portrayed.

Conclusion

In order to answer the initial questions: What is the role of pictures in the ICT4D? How are images involved in social change? This essay starts the conversation on stereotypes, namely how stereotypical imagery reinforces structural racism, as a heritage of the colonial West, supporting the misconception that the Global South is inferior. Then, the essay explores the concepts of ‘white savior’ and ‘poverty porn’, inappropriate use of images or clips on social media and in advertisements. Lastly, we have seen how IC4T could support social change initiatives and fight inequalities.

Visual representation is a very broad topic, and involves many actors. It is important to understand the importance of appropriate pictures in any situation and the social responsibility of each actor. To have a positive impact, a good use of images on ICT for social change should be performed on a micro level, from individuals, as well as on a macro level, from institutions and organizations. In this regard, social media platforms are a significant space for sharing thoughts, gathering ideas, raising voices and so on.

In the era of social media, inspirational material for social change and good practices of development campaigns is always available. On the web, many people raise their voices and stand for what is right. For example, in the case of pictures one big step that should be done by INGOs and organizations is to value more local knowledge. Moreover, to have a real shift to a more equal society, the non-Western population should have the possibility to “hold structural power” (Peace Direct, 2021).

References

Ademolu, E. & Warrington, S. 2019: Who Gets to Talk About NGO Images of Global Poverty?, Photography and Culture, August.

Denskus, T., 2019: White saviour communication rituals in 10 easy steps, Aidnography, 5 March.

Gordon G. 2012: The Power of Images: Who Gets Made Visible?. In Beyond #Kony2012: Atrocity, Awareness + Activism in the Internet Age, Leanpub ebook.

Hall, S., Evans, J. and Nixon, S. (ed.) 2013: Representations. Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices, Second Edition. London: Sage.

James, W. 1892: The Self. In Social Media & the Self: An Open Reader (1st ed.). mediastudies.press.

Pooley, J. 2021: Social Media & the self-An open reader. Mediastudies.press.

Peace Direct (2021): Time to Decolonize Aid-Insights and Lessons from a global consultation. London: Peace Direct.

Schwarz, K. & Richey, L.-A. 2019: Humanitarian humor, digilantism, and the dilemmas of representing volunteer tourism on social media, New Media & Society, 21:9, 1928-1946.

Scott, M. 2014: Media and Development. London: Zed Books.

Shringarpure, B. 2020: Africa and the Digital Savior Complex, Journal of African Cultural Studies, 32:2, 178-194.

Warrington, S. and Crombie, J. 2017: The People in the Pictures: Vital Perspectives on Save the Children’s Image Making. London: Save the Children UK.

Internet links

https://authoritycollective.org/

https://twitter.com/hashtag/InclusivePhotography?src=hashtag_click

https://wpmu.mau.se/nmict21group3/2021/10/04/rethinking-images/

https://wpmu.mau.se/nmict21group3/2021/10/19/volunteer-pictures-on-social-media/

https://www.everydayprojects.org/

https://www.instagram.com/barbiesavior/?hl=fr

https://www.instagram.com/humanitariansoftinder/

Personal considerations

This blog post and the other ones I wrote on this blog talk about pictures. In my job, I get to select, choose and create a lot of visual material, and in my private life too, since I regularly post pictures on my private Instagram account. Almost everyone knows the power of images, but not everyone knows that they contribute to creating racial discourse, and that they were used as an educational material also during Imperialism. A deeper analysis on historical representations during colonial times is a useful way to get a better picture of today’s problematics.

In our private lives, many of us on social media produce images, which are shared without thinking too much on the consequences or the signifiers of those images. I believe this is the reason why the blog post “Would you volunteer if you couldn’t share pictures on social media?“ got one of the highest number of comments on this blog. I guess, people felt personally involved, me included. Having now tools to share and gather information helps to create awareness and exchange knowledge. This was also the aim of this blog, to create a space for dialogues among students, professionals and people with interest in development and social change.

Also, considering the interest (not only mine, but also from my peers) in humanitarians and social media, I found it hard to make a decision on the main topic of this last blog post. I was tempted to elaborate the theme only on the humanitarian self and social media, but this would have been less useful for professionals, me included. Moreover, I wanted to give the same importance to the personal actions and the role of organizations, as we are all involved in social changes at different levels. For these two reasons, I present an overview of my two previous posts on images and photography in the humanitarian world.