Throughout the history of human civilization, narratives have played crucial roles in legitimizing, establishing and maintaining power structures around the world, both between and within social and political groups. One of the most practical examples is in the history of western colonialism, where manufactured stereotypical depictions of the colonized as underdeveloped justified centuries of Western domination and exploitation of foreign lands, people and resources.

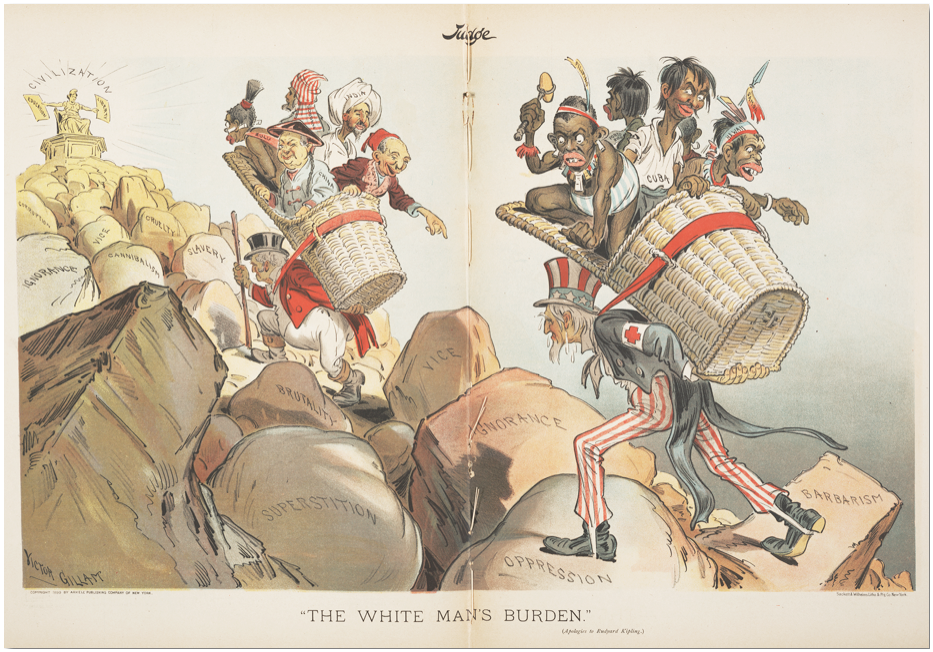

Yet the artificial cognitive structure that divided the world into ‘developed’ and ‘underdeveloped’ not only justified colonialism and legitimized its violence, it also elevated colonizers to the role of selfless bearers of progress driven by a moral duty. Subjugation and domination were disguised as charitable acts of wellbeing by a distorted narrative centered on the myth of ‘the white man’s burden’.

So deep has the myth of ‘the white man’s burden’ penetrated in Western structural knowledge, that today it still affects the Western general public’s understanding of colonialism: as indicated by the article “How Britain stole $45 trillion from India. And lied about it” (2018) by Jason Hickel, published on Al Jazeera’s official website, “according to a 2014 YouGov poll, 50 percent of people in Britain believe that colonialism was beneficial to the colonies”.

When observing how the idea of colonialism as a developing mission has survived in the West until the present day, it is inevitable to take into consideration public representations of relationship between the Global North and the Global South that reach the Western general public today. As it has often being critically observed, development organizations and the media still have a tendency to portray the Global South as desperate and helpless, perpetuating the understanding that it is unable to fend for itself. Although in some cases there are concrete motivations behind these representations, such as humanitarian organizations’ need to attract funding or gain visibility, the consequences and implications are still deeply problematic.

The risks and ethical implications that come with the construction of disempowering, stereotypical representations of the Global South is now a topic debated not only in academic literature, but also critically discussed on the media as well as by development actors themselves. Over the next weeks however, I will be looking at the other side of the coin: what are the current trends in representations of the Global North, humanitarian workers in particular? Have these narrative structures evolved over the past centuries and decades, and how? How do they impact humanitarianism and development and shape by contrast representations of the South?