About 4 years ago I purchased a sewing machine. I had for a long time thought of sewing as an old-fashioned skill, which was out of sync with my idea of modern womanhood. But then I found myself living abroad in a place where I was surrounded by a wealth of gorgeous fabrics, creative local designers, and a group of fierce female friends who turned my assumptions upside down. So I decided it was time to learn.

You may wonder what this has to do with discursive activism in online communities – I promise, this will be clear in a moment.

I started teaching myself with a book I found for beginner sewists, working my way through basic projects in my spare time – pillow cases, tote bags, zipper pouches, etc. As I progressed, I turned to the internet and social media for more resources, where I discovered a vibrant online sewing community, particularly on Instagram.

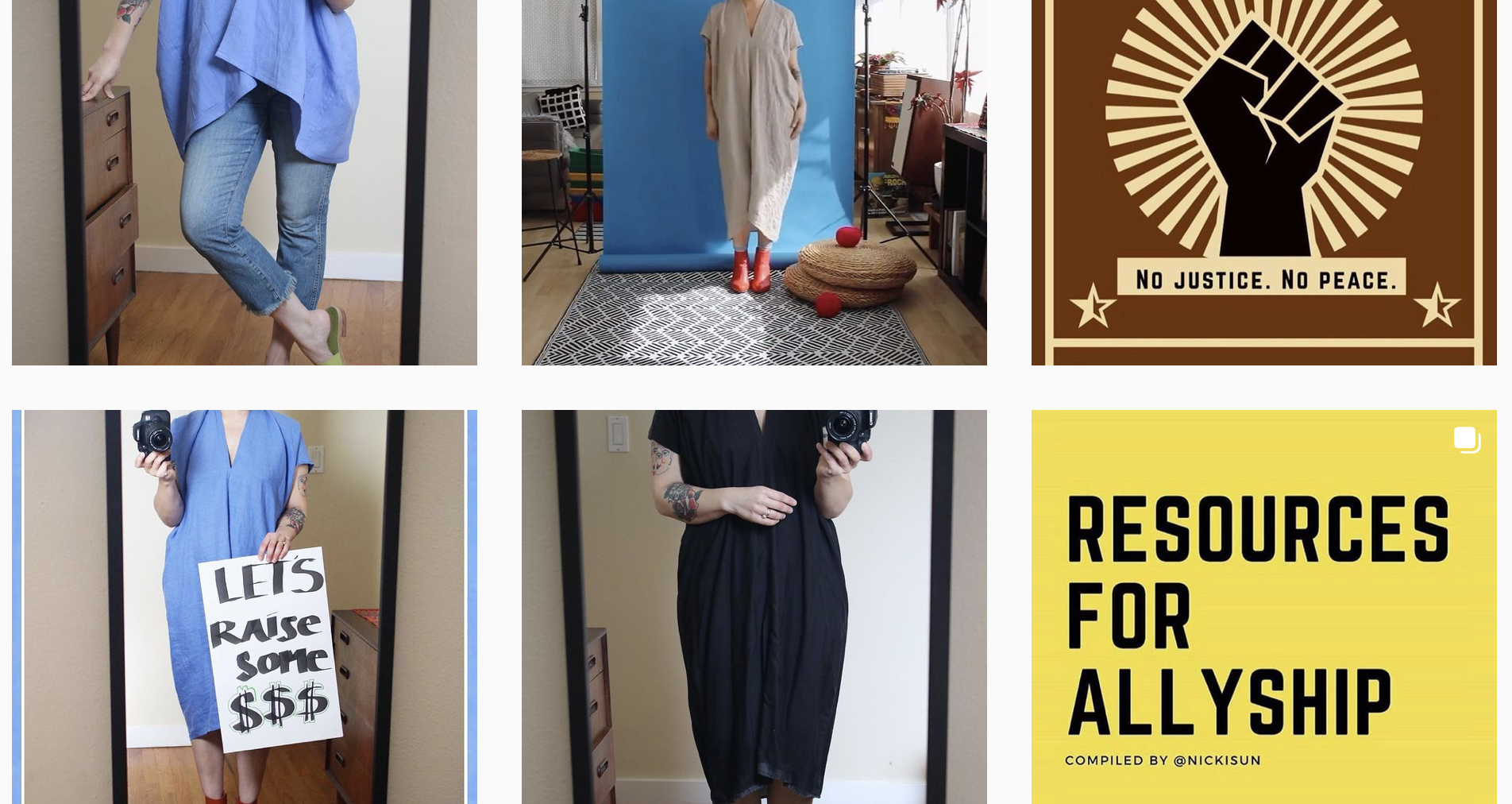

There are so many accounts it is hard to generalize. But if I may try – most of these accounts are dedicated to sewing handmade wardrobes and other fiber-related projects, including knitting, crocheting, and weaving. Some are individual sewing diaries, others are independent businesses, and some are a mix of both. They act as resources for other sewists and makers, and share useful information on pattern-hacking, fabric choices, and equipment. Some are serious and reflective, others light and humorous. They use common hashtags, participate in community challenges and promote each other’s work. Those in my network are mainly run by women based in the US or Europe who share wistful candid photos of themselves, or their family and friends, in gorgeous, often flowy, handmade garments.

While sewing my own clothes wasn’t initially my goal, I was drawn in by the community’s creativity and engaging content, and I dove into their accounts for inspiration.

It just so happened that at this same time, I also started this study programme in Communications for Development. As I got deeper into readings about technology and activism, I began to consume social media differently, and I started to consciously notice the undercurrent of discreet activist messaging running through many posts within the Instagram sewing community. This got me thinking about more subtle forms of activism that play out in common online spaces everyday, and their role in challenging social norms.

Which brings us to discursive activism – I was not fully aware of this term when I started writing this post and it took some time to be able to name the thing I was looking for, which is, “activism that aims to produce social change by changing language, media representations, social discourse and so on.”

Much of the literature I came across focuses on online discursive activism within social movements, and often considers the use of social media hashtags (for example, #metoo). But what about in less obvious online communities, where people interact around common interests that are not inherently political in nature?

The Australian researcher Frances Shaw, who has written fairly extensively on discursive activism in her local feminist blogging network, highlights the importance of culture in social change. She writes that, “In his [Melucci’s] view there are social movement actors who prepare the public for political change through cultural discourse, and other actors who then ‘process’ the issues through political means (Shaw 2011, 379).” Similarly, in Tufecki’s more recent work “Twitter and Teargas,” she discussed the power that exists in social media when people send cultural signals that, over time, make social change possible.

Sewing as a hobby or small business seems far removed from politics or social justice, but many of the accounts I follow create content that feeds into messaging that runs the gamut of political and social issues, from racial discrimination and climate justice to sustainable consumption, body positivity, diversity and inclusion, and reaches in the tens- to hundreds-of-thousands of followers.

As an example, every year many of these creators participate in the #memademay challenge. The idea is to post a daily photo of yourself wearing your own handmade garments for the entire month of May. Though one could argue that the challenge is somewhat superficial in nature, one could also argue that its immediate theme (and that of the community as a whole) is a counter-discourse to the way we engage with fashion today. And this discourse overlaps with larger movements, such as the environmental and sustainability movements.

Outside of #memademay, there is regularly posted content about ways to reduce fabric waste, as well as the virtues of visible mending and second-hand clothes. Creators also often discuss their efforts to be an intentional consumer i.e. only buying fabric with a specific project in mind and focusing buying power on sustainable fabrics with minimal environmental impacts. There are regular discussions around body positivity, particularly as it pertains to inclusive sizing, as independent pattern-makers aim to include a range of sizing that reflects a wide variety of body types. And a number of accounts engage in discourses on accessibility by posting text descriptions of their images in the comments to allow individuals with visual disabilities to engage with their posts via text reader.

The messaging is discreet and localized to the context of this specific community. But nevertheless it is there, chipping away bit by bit at dominant discourses and feeding into the context of larger social movements.

I don’t know whether the creators behind these accounts would define themselves as activists. As we can see in the comments on my previous post, and in those from my peers, how one sees themselves in relation to activism is highly personal. I also don’t know to what extent they make a conscious effort to include such messaging in their content, or if it is simply a natural extension of their interactions with followers when sharing their personal beliefs and values.

However, the more we look at the meaning of activism in a digital world, the more the lines blur between what is and what is not activism. And just as I talked about the possibility of constructing activist identities through social media in my previous post, I believe this online community may be an example of that process.

It is worth considering the way in which the lines between activism and regular content have started to blur in our everyday online interactions and the effect this has on the construction of our identities and values as individuals and as activists.

I would argue that the Instagram sewing community, with its more subtle “cultural signals” and the values that it promotes, can be an effective actor in “preparing the public for change (Shaw 2011, 379)” by engaging followers in counter-discourses in ways that are meaningful to them and that resonate with their interests.

What do you think?

Are you involved in any online communities centered around a specific hobby or interest?

If so, what messaging and values are shared among members?

And how has that impacted you and your own personal values and activism?

Reference material:

- Shaw, F. (2011). (Dis)locating Feminisms: Blog Activism as Crisis Response. Outskirts, 24.

- Shaw, F. (2011). ‘Hottest 100 Women’: Cross-platform Discursive Activism in Feminist Blogging Networks. Australian Feminist Studies (27)74, 373-384.

- Tufekci, Z. 2017: Twitter and Tear Gas-The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- https://www.igi-global.com/chapter/collective-voices-online/259542

- Click on the screenshots above for links to the Instagram accounts referenced.