On 21 September 2020, We See You, a ‘POC feminist queer collective of artists and activists’ announced their occupation of a mansion in Camps Bay, Cape Town, South Africa. After renting the home through Airbnb, the collective did not depart on their check-out date and began an approximately two-week-long occupation. Their objective was to highlight the lack of safe housing for vulnerable people during the COVID-19 pandemic, in particular people who are LGBTQIA, and to protest housing and income inequality in Cape Town and across South Africa.

As with many present-day activist interventions or social movements, digital technology played a role in the execution and coverage of the We See You occupation. Informed by research and theory on the relationship between activism and digital technology, this post will examine the We See You occupation, and discuss how digital technology both advanced and challenged the collective’s aims. A concluding section will reflect on whether digital technology has the potential to support activism and advance the national dialogue on land reform and inequality in South Africa – one of the country’s biggest development challenges.

My approach and positionality

As a South African, I followed the We See You occupation as it unfolded via Instagram, from my home in New York City. I was struck by the collective’s strategy: while occupations of vacant public land or disused buildings are not uncommon in the country, their decision to occupy private property in an exclusive suburb was, at least to me, unheard of. In choosing to focus on this act of protest I reviewed existing coverage and analysis of We See You. While the occupation received a lot of media coverage, there was insufficient insight into the collective’s strategies to make a meaningful analysis possible. I therefore reached out to We See You and interviewed three of the individuals who participated in the planning and occupation – Xena Scullard, Vateka Halile, and Devaarne Muller. In addition to news coverage and interviews, I reviewed content and interactions on We See You’s social media channels.

Context

It is beyond the scope of this post to properly situate the We See You occupation in the context of South Africa’s history of land dispossession and inequality, or within the context of global movements of squatting and occupation. However, a brief summary is necessary to understand We See You’s objectives and tactics.

The legacy of land dispossession

Over 400 years of colonial and Apartheid policies designed to systematically dispossess black South Africans of land and the ability to own property continue to have a profound impact on the lives of people today (Ngcukaitobi, 2021). The World Bank describes South Africa as having “one of the highest, persistent inequality rates in the world” which has been in part “perpetuated by a legacy of exclusion and the nature of economic growth”. Regardless of how one looks at available data, white South Africans, who make up less than 10 percent of the population, own the majority of individual-owned land. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many South Africans – including some members of We See You – lost their sources of income, as well as access to safe and dignified shelter. Furthermore, in the city of Cape Town, certain media outlets and the local government have labeled people seeking access to land and shelter as invaders – a term that the We See You collective rejected and wished to challenge:

The homeless were being labeled as invaders…but what are they invading? If you live in the city and you are demanding a safe space to live or a place with the bare minimum to survive, why is there this rule that you cannot demand that? It’s a human right – Devaarne

Solidarity with global occupations

“We are in solidarity with occupations globally, but especially locally as police brutality illegally removes occupiers from their homes. #holdyourground”. This tweet from We See You, posted the day their occupation began, clearly situates their act of protest within a bigger global movement of occupation and squatting. Throughout the 20th and 21st centuries, squatters and occupiers across the world have sought to meet urgent housing needs, to challenge the politics of who has the right to the city, to form communities, and to imagine alternative ways of being (Vasudevan, 2017). In my interviews, members of the collective reflected on being inspired by other occupations and movements. However, beyond serving as inspiration, We See You did not have direct engagement with any of these global movements, and expressed some disappointment that this did not occur.

We See You and the significance of Airbnb

The collective used the popular global platform for short-term rentals, Airbnb, to book a stay at the home in Camps Bay. I asked them whether this was the simplest way to gain access, or whether it was significant that the home was listed on Airbnb. Globally, the digital platform has been the target of many campaigns against gentrification and the rising cost of housing, particularly in popular tourist destinations like Barcelona and New Orleans. While Airbnb states that its presence in a city creates new sources of income generation for individuals, research has found that the platform can negatively impact communities by increasing rental costs and reallocating available housing from the long-term to the short-term market (Barron et. al., 2019).

The collective members I spoke with explained that using Airbnb was strategically relevant to their messages about the lack of access to housing and inequality in Cape Town. They spoke about how platforms like Airbnb enable property owners to repurpose their spaces towards short-term, typically holiday rentals, while the city struggles with housing – and that these rentals are often empty. According to Inside Airbnb, an activist project that uses data to analyze the platform’s impact on the housing market, the high availability rate (88.4 percent) of listings in Cape Town suggests that owners are likely not present and that properties are being used specifically for short-term rental. Airbnb (2018, p.23) states that in South Africa, its platform provides an important way “to make ends meet” for its hosts. However, the fact that so many listings appear to be unoccupied by the owners, and therefore unlikely to be first homes, strongly suggests that the platform mostly benefits those who are already privileged and financially secure.

Platforms like Airbnb may not be the types of digital platforms we immediately think of when discussing activism in the digitally networked era. However, as this example shows, digital platforms not only create new ways for activists to work, but they may also be driving new activist causes as they introduce or magnify societal inequalities.

Hear us.#weseeyou#takeupspace#webelonghere#occupyhome#holdyourground pic.twitter.com/bqhKgJkTB5

— We See You (@WeSeeYou_2020) September 22, 2020

Counterpublics and Social Media Engagement

In Hashtag Activism: Networks of Race and Gender Justice, Jackson et al. (2020) examine how today’s activists and movements, as part of counterpublics, use social media platforms to challenge and change narratives, encourage action, educate, create communities and celebrate marginalized identities. Although their work focuses on Twitter, their observations and findings are relevant to other platforms.

My analysis of the collective’s social media engagement takes place within the framing of We See You as a part of a counterpublic. Counterpublics are “alternative networks of debate created by marginalized members of the public, [which] have always played an important role of highlighting and legitimizing the experiences of those on the margins” (Jackson et al., 2020, p. xxxiii). The phrase ‘we see you’ is a direct acknowledgment of and identification with those who are typically unseen or forced to hide in society – both the unhoused and people who identify as LGBTQIA. Yet, the phrase can also be interpreted as a direct challenge to those who oppress and marginalize – their acts being made visible.

Aside from using digital tools in the planning of the occupation, We See You sought to use social media to raise awareness and challenge dominant narratives. The collective developed a strategy for their social media content and moderation but were candid that, once the occupation began, it became challenging to adhere to it. A review of their content on social platforms reveals a mixture of statements about the occupation and its mission, content about social and wealth inequality in South Africa, art, and vignettes about the individuals in the collective. On Twitter, the collective also retweeted supportive messages from individuals and various local social justice organizations. While the official following of their social media accounts was modest (currently there are 1,446 people liking the page and 1,532 following them on Facebook, 721 followers on Instagram, and 221 followers on Twitter), engagement with the content on Facebook was particularly high with many posts attracting multiple comments.

Unlike many examples of digital activism where the media begins to cover stories after they reach a critical mass on social media, We See You planned direct media outreach as part of their strategy. The collective quickly found themselves dealing with multiple media requests and coverage in some of the country’s biggest media platforms. Overall, the collective members who I spoke with felt that, while some media represented the occupation well, many did not and some, like the Daily Voice, used deeply homophobic language in their reporting. Such negative or derogatory reporting exemplifies the type of trivialization and hostility that mainstream media sometimes demonstrate towards social movements for ideological or corporate reasons (Tufekci, 2017, p.30). In this context, the collective members recognized the importance of social media for presenting their own narrative: “The only real way we actually had to say our pieces directly from our own mouths was through social media,” Devaarne Muller told me.

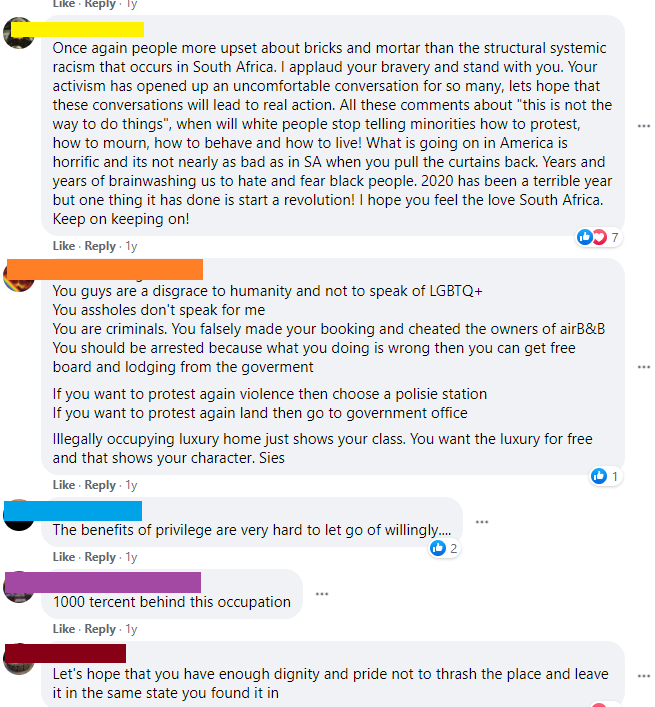

Social media, bullying, and harassment

An informal analysis of We See You’s content across their social media channels reveals a high volume of negative comments. Many of these take issue with the collective’s form of protest and deploy racist and homophobic narratives, seemingly unhindered by the fact that these comments are linked to the commenters’ real names. Some public comments even threaten violence. In addition to the hateful comments on the collective’s pages, many dealt with harassment via their personal accounts. The members of the collective that I spoke to recounted how much toll cyberbullying took on them, despite knowing that they would face backlash.

It felt like they had been looking for something to attack and we were just the target. And the racism was just too much – Vateka Halile

…the way people had the time to harass continually, making fake accounts, we block an account and then they’d make another account…[it was] relentless – Devaarne Muller

In addition to online harassment, the activists also faced comments attempting to discredit them on account of their perceived class affiliation or the fact that some of the collective members were not originally from Cape Town. Even in the absence of evidence of the kinds of orchestrated attacks described by Tufekci (2017), the case of We See You makes it clear how social media can be weaponized and used to discredit a protest.

Data costs: a challenge to online activism in the Global South

Once the occupation officially began, the activists soon found themselves without access to Wi-Fi, as well as other amenities, as these were cut-off by the property management company responsible for the house. The reliance on mobile data presented a significant challenge to the collective’s online engagement. A recent analysis ranked South Africa in 136th place globally for data affordability. Reflecting on this, collective member Xena Scullard noted that it is a struggle for organizations, and more so groups of activists, to fundraise for core costs, including resources like mobile data.

In the case of We See You, the activists relied on personal finances as well as contributions from supporters and allies of the occupation who sent data as well as electricity vouchers, food, and personal care products. What this experience highlights, is that for the public and activists alike, the cost of data can be a prohibitive barrier to civic and protest action – a phenomenon that is largely absent from accounts of activism in Global North countries where data costs are significantly lower or where free public Wi-Fi is widely available.

Land reform, activism, and the digital sphere

More than a year has passed since We See You vacated the Airbnb following a court order. In September 2021, Cape Town passed the ‘Unlawful Occupations’ bylaw, which has been criticized by housing activists for criminalizing the unhoused. In early October 2021, Cape Town law enforcement raided Cissie Gool house, a former hospital building, and another occupied property in the city. Access to safe housing remains a huge challenge to many vulnerable South Africans, and there is a consensus that the country’s vision for land reform post-1994 has largely failed (Ngcukaitobi, 2021). The Expropriation Bill, proposed by the Government with the intention of accelerating land reform, has raised anxiety among private property owners, and warnings from political opponents and think tanks about its impact on foreign investment and the economy overall.

As this brief post reveals, social media is one space where public debates about land and inequality in the country play out. Activists like We See You, as well as social justice organizations like Tshisimani, Ndifuna Ukwazi and others, form a counterpublic and are using social media platforms to educate and raise awareness, elevate marginalized voices, and challenge narratives which characterize unhoused people as ‘invaders’. At the same time, this often comes at a great personal cost to the activists themselves as they encounter violence and harassment online. Despite South Africa’s relatively high internet penetration, the cost of devices and data means that access to social media platforms is still limited for the most vulnerable, thus curtailing their potential as spaces of deeper engagement. And, while We See You reached a broad audience, more and more research reveals how echo chambers form on social media platforms and activists and social justice organizations are often likely to be engaging with the already ‘converted’ and those who support their objectives (Tufekci, 2017, p.271).

A final reflection

Over the two months that I have been exploring the relationship between activism, digital technology, and development, through case studies, interviews, and course literature, I have developed a more nuanced understanding of how these spheres interact with one another. A related question I kept coming back to is how to assess the impact or success of digitally-powered activism, especially when digital metrics do not always correspond to the underlying capacity of activist groups or movements (Tufekci, 2017). As internet penetration grows and digital technologies play increasingly larger roles in our lives (even in ways we are not aware of) it is crucial to look closely at the affordances and limitations of digital technologies for activism and to avoid overgeneralizations that characterize digital technology as either a panacea or obstacle. As the We See You case study shows, while digital platforms played a role in their planning, execution, outreach, and even enabled them to receive in-kind support, staging their protest still drew on approaches and relationships that are not digital.

I would like to express my gratitude to Devaarne, Vateka, and Xena for agreeing to speak about their experiences in planning and executing the occupation. I spoke with Devaarne and Vateka on 16 October via Zoom, and with Xena on 26 October via a WhatsApp call. We also exchanged messages for additional insights and clarifications via a WhatsApp group during October and November 2021.

Reference List

Airbnb. (2018). Airbnb in South Africa: The Positive Impact of Healthy Tourism. Airbnb. https://press.airbnb.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/4/2018/09/Airbnb-in-South-Africa-Positive-Impact-of-Healthy-Tourism.pdf

Barron, K., Kung, E., and Proserpio, D. (17 April 2019). Research: When Airbnb Listings in a City Increase, So Do Rent Prices. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2019/04/research-when-airbnb-listings-in-a-city-increase-so-do-rent-prices

Dube, T. (19 July 2019). Do white people own ‘only’ 22 percent of South Africa’s land?. AFP Fact Check. https://factcheck.afp.com/do-white-people-own-only-22-percent-south-africas-land

DW News. (4 September 2020). Concern in South Africa over pandemic squatter camps. DW News. https://www.dw.com/en/concern-in-south-africa-over-pandemic-squatter-camps/av-54822462

Graham-Maré, S. (3 September 2020). Double standards could be our downfall in the war on land invasions. The Democratic Alliance. https://www.da.org.za/2020/09/double-standards-could-be-our-downfall-in-the-war-on-land-invasions

Human, L. (29 September 2021).Cape Town passes Unlawful Occupations by-law, despite protest. GroundUp. https://www.groundup.org.za/article/cape-town-passes-unlawful-occupations-law-despite-protest/

Inside Airbnb. (29 September 2021). Cape Town [data visualization]. http://insideairbnb.com/cape-town/

Jackson, S., Bailey, M., and Foucault Welles, B. (2020). #HashtagActivism: Networks of Race and Gender Justice. The MIT Press

Litten, K. (27 September 2016). Neighborhood ‘mourners’ want New Orleans short-term rentals regulated. Nola.com.https://www.nola.com/news/politics/article_5e75f498-fe1e-5160-962c-aa3a39deddf6.html

Majola, G. (11 April 2021). SA ranks 136 worldwide for the cost of mobile data. IOL. https://www.iol.co.za/business-report/companies/sa-ranks-136-worldwide-for-the-cost-of-mobile-data-e2536315-ed01-4eab-a0f5-ec101398a0d4

Mead, R. (22 April 2019). The Airbnb Invasion of Barcelona. The New Yorker. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/04/29/the-airbnb-invasion-of-barcelona

Ngcukaitobi, T. (2021). Land Matters: South Africa’s Failed Land Reforms and the Road Ahead. Penguin Random House South Africa

Qodashe, Z. (14 October 2021). Businesses may be afraid to invest in SA because of land expropriation proposal: FF Plus. SABC News. https://www.sabcnews.com/sabcnews/businesses-may-be-afraid-to-invest-in-sa-because-of-land-expropriation-proposal-ff-plus/

Seleka, N. (11 April 2021). City of Cape Town hit by 1 025 land invasion incidents since March 2020. News24. https://www.news24.com/news24/SouthAfrica/News/city-of-cape-town-hit-by-1-025-land-invasion-incidents-since-march-2020-20210411

Stoddard, E. (20 September 2021). South Africa’s ‘dangerous’ land policy under scrutiny in Fraser Institute report. The Daily Maverick. https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2021-09-20-south-africas-dangerous-land-policy-under-scrutiny-in-fraser-institute-report/

Sweat [@SweatTweets]. (1 October 2020) #CampsBay occupation statement: ‘We understand the realities of homelessness; brutalities marginalised people face and the consistent lack of [Images attached] [Tweet]. Twitter. https://twitter.com/SweatTweets/status/1311750879263981571?s=20

The World Bank. (2021). The World Bank in South Africa – Overview. https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/southafrica/overview#1

Tshisimani. (15 October 2021). Early this morning Law Enforcement closed off Mountain Road and are raiding Cissie Gool House, armed to the teeth with [image attached] [Post]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/tshisimaniCAE/posts/2510472302429431

Tshwete, M. (23 September 2020). Your gays are numbered. Daily Voice. https://www.dailyvoice.co.za/news/your-gays-are-numbered-3259dc42-d20f-46e5-8e80-b01fff6f1ba7

Tshwete, M. (25 September 2020). Live to fight another gay. Daily Voice. https://www.dailyvoice.co.za/news/live-to-fight-another-gay-cc64561d-9051-4376-8be7-2ac533afb92d

Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Yale University Press

Vasudevan, A. (2017). The Autonomous City: A History of Urban Squatting. Verso.

We See You. (21 September 2020a). Press Statement – Queer Artivists Occupy Camp’s Bay Mansion [image attached] [Post]. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/weseeyou.now/posts/128145889008717

We See You [@WeSeeYou_2020]. (21 September, 2020b). We are in solidarity with occupations globally, but especially locally as police brutality illegally removes occupiers from their homes. #holdyourground [Tweet]. Twitter https://twitter.com/WeSeeYou_2020/status/1307945809678348288