While researching a paper on social movements last year, I learned about an activist social media platform called “Chalk Back” that captured my interest. Through the simple act of recording utterances of real-life street harassment in colorful chalk on the sidewalks where they occur in cities around the world and broadcasting the images via their various localized Instagram accounts, the group “chalks” back to harassers to raise awareness about the harassment women face on public streets everyday. However, as I dove into Chalk Back’s Instagram content, I was struck by one video in particular posted by Sophie Sandberg, the group’s founder, who detailed her experience being stalked and harassed via – you guessed it – Instagram.

Sandberg’s experience came back to mind recently while reading Zeynep Tufecki’s chapter on “Names and Connections (2017, pgs. 164-188).” She shares the stories of several female activists in Turkey who recount instances of online harassment via Twitter, resulting from their engagement in political activism on the very same platform. She highlights that while Twitter was seen by its founders as a way to “speak truth to power (Tufecki 2017, pg. 176),” the platform offers little protection for women who try to do so.

Around the same time, I received an email newsletter featuring a comic strip by illustrator/writer Aubrey Hirsch entitled “How to Be a Wom an on the Internet.” The very first frame depicts a woman, masked as a man, with the following instructions – “First, if you can help it, don’t be.”

an on the Internet.” The very first frame depicts a woman, masked as a man, with the following instructions – “First, if you can help it, don’t be.”

These stories, videos, and images represent just a small part of the ever-growing chorus of female voices speaking out against the harassment women experience when engaging in online spaces. The repetition of this message that the internet and social media are not a safe place for women, particularly those who openly speak their mind, hits home. I question if women are truly being heard and represented in online debate when so much of their energy is spent navigating abuse, fending off harassers, and controlling their online presence? Why does this keep happening? Who is responsible? And what is being done about it?

An overview: data, definitions and framing

According to data from the 2021 Pew Research Poll visualized in Hirsch’s comic, 47% of women have been harassed online because of their gender, a percentage that only increases for women at the intersection of various racial, sexual or gender identities. Though Hirsch’s illustrations draw on data collected in the US, this issue transcends borders. According to an open letter drafted by 200+ influential women for the 2021 Generation Equality Forum and addressed to the CEOs of Twitter, Facebook, Tiktok and Google:

The scale of the problem is huge: 38% of women globally have directly experienced online abuse. This figure rises to 45% for Gen Zs and Millennials. For women of colour, for Black women in particular, for women from the LGBTQ+ community and other marginalised groups — the abuse is often far worse. The consequences can be devastating.

It’s not to say that men do not also experience online harassment. However, given the disproportionate rates at which women face harassment, the term that is generally employed to describe this phenomenon across literature is gender-based online harassment. The issue is furthermore situated as a form of gender-based violence (or more specifically “online gender-based violence”). Amnesty International makes this connection in their 2018 report entitled “Toxic Twitter,” drawing on the UN CEDAW’s definition of gender-based violence, which refers to violence that “…is directed against a woman because she is a woman or that affects women disproportionately.”

This framing recognizes the systemic and damaging nature of such abuse, that online harassment is not simply a communication issue, nor are its psychological or physical effects limited to the online realm (Lewis et al., 2017). Rather it recognizes the internet as “a site of social and cultural production that reflects real-world patterns (Lewis et al., 2017, pg. 1464),” where the power relations and imbalances that exist offline are reflected in our online interactions. These power relations, including gender and identity-based inequalities, determine who enjoys access to and the benefits of ICTs (O’Donnell et al., 2018, pg. 217).

It follows logically then that the internet and digital media are not gender neutral (O’Donnell et al., 2018, pg. 217). This is supported by Tufecki who argues that as the rights of one group (e.g. women and minorities) clash with the rights of another online (e.g., those who seek to silence them), existing power imbalances come to the fore and neutrality is lost (Tufecki 2017, pg. 178). The effect is such that digital spaces no longer feel safe to women. Indeed, according to a 2020 global survey conducted by the Economist’s Intelligence Unit, half of women felt the internet was not a safe place to share their thoughts. Hirsch’s illustrations describes the experience as such:

Whatever kind of woman on the internet you are, you already know you have to be careful and smart… You have to be guarded even when trying to appear vulnerable… You have to hide, even if your goal is to be seen… You have to be stingy, even when you share.

This is a nearly impossible balance for women to strike, and we see this reflected in the same survey data from the Economist who reports that nearly 9 in 10 women surveyed restrict and self-censor their online activity. To this point, Amnesty International’s Toxic Twitter Report refers to the UN CEDAW, who write that,

…a woman’s right to a life free from gender-based violence is indivisible from, and interdependent on, other human rights, including the rights to freedom of expression, participation, assembly and association.

In this way, the gender-based harassment and abuse that women face in online spaces, is not only a form of gender-based violence, but also a violation of their basic human rights.

Digital solutions: the pros and cons

Having set the stage, where do we go from here? How is the issue being addressed and who is responsible? Though the answer to these questions is not straightforward, influential women leaders at this year’s Generation Equality Forum – in the same letter mentioned previously – place the responsibility squarely on the shoulders of tech industry giants, specifically Google, Twitter, Tiktok and Facebook, writing,

“Your decisions shape the way billions of people experience life online. With your incredible financial resources and engineering might, you have the unique capability and responsibility to ensure your platforms prevent, rather than fuel, this abuse.”

Through the course of the letter the authors recognize that the tech industry has taken the first step by entering into dialogue with civil society and governments in a number of countries. Still, they call upon CEOs to go further in preventing online gender-based violence in their respective platforms.

To this end the World Wide Web Foundation held a series of multi-stakeholder consultations, known as the Tech Policy Design Lab, in the run up to the 2021 Generation Equality Forum. These consultations aimed to co-create prototype solutions for social media platforms, defining the issues to be addressed specifically from the perspective of women with intersectional identities who are both vocal and visible in online spaces.

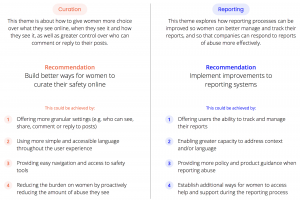

As a result of the workshops, the Design Lab identified two key areas for commitment – curation and reporting:

Curation interventions focused on ways to offer users better control of their privacy settings, easier user interface and access to security features, and tools to reduce the amount of abuse received by women. Reporting interventions focused on parallel issues of improving user’s ability to track reports of instances of abuse, as well as better back-end response to such reports in terms of recognizing cultural and language differences (World Wide Web Foundation, 2021).

These intervention areas were translated into prototype app functions that, for example, generate system alerts that allow users to quickly stem a flood of comments, or that allow community support in moderating an influx of abusive feedback. Other prototypes offer systems that can potentially recognize a user’s image in external content posted by other accounts and flag it, as well as reporting systems that offer better communication flows and options, including the possibility to request protected status in the event of abuse (World Wide Web Foundation, 2021).

Despite the innovative nature of the prototypes, there are limitations. For example, artificial intelligence systems have a weak capacity to recognize and understand context. So how does the system determine the point at which an individual user is becoming overwhelmed with incoming feedback? For an average user with a small following it might not take much, whereas a seasoned activist or a public figure with thousands, if not millions, of followers might have a much higher threshold (World Wide Web Foundation, 2021).

Systems also have a weak ability to recognize when incoming feedback is actually abusive. The aspect of recognizing cultural and language differences comes into play here, as abusive words and content can be context-specific (World Wide Web Foundation, 2021). Systems, and even the individuals building them, may lack this overall capacity for this level of nuance.

Tech industry leaders have signed on to these commitments and it is a step in the right direction. These prototypes also offer useful, innovative tools that can provide protection to women. However, such solutions do not get at the root of online gender-based violence. In a way, it feels akin to putting up reflective, soundproof glass between women and other users; you may no longer hear or see the crowd of people yelling and screaming, but that doesn’t mean they are not there, or that they’ve stopped.

Changing social norms and building a feminist internet

The critical question is then, does a digital solution to online gender-based harassment even exist? To a certain extent, I would argue no. According to O’Donnell et al., “Online is an environment where the social norms that justify and perpetuate GBV, normalising it as an everyday aspect of gender relations, are alive and flourishing (2018, pg. 223).” Given that such norms are grounded in offline power relations, it follows that a systemic offline response is needed in parallel to a digital response. This is where tools and concepts from the development and activist community may have a role to play.

UN agencies and NGOs are already at the forefront of work addressing social norms across a variety of issues affecting women’s rights and empowerment. In this work, development programmes often employ “gender-transformative approaches,” which aim to “address the causes of gender-based inequalities and work to transform harmful gender roles, norms and power relations (UNICEF, n.d.).”

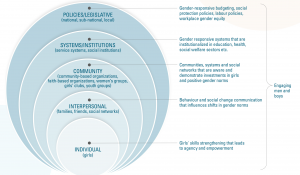

UNICEF describes this approach through a gender equity continuum:

They apply this through a socio-ecological model (SEM), which guides the approach by looking at the “complex interplay between individual, relationship, community, and societal factors (CDC.gov, 2021)” :

Employing this model, organizations attempt to address harmful norms at the individual, interpersonal and community level, with a goal to ultimately influence the design and implementation of more gender-responsive systems and policy.

“Gender transformation” (UNICEF, n.d.) is already widely deployed as a tool in women’s rights and anti-gender-based violence programming. Accordingly, existing programming may be further enhanced by including considerations about the parallel reality women face in online spaces. In this regard, the “Feminist Principles of the Internet” offer a useful conceptual framework.

These principles, of which there are 17, were elaborated by activists at the first “Imagine a Feminist Internet Meeting” held in 2014 in Malaysia, seek to reimagine an internet grounded in feminist thought. The principles are organized into five clusters (Access, Movements, Economy, Expression, and Embodiment) and emphasize, for example, the need for women’s access to, as well as their implication in the coding and design of, the internet and ICT tools. They also highlight the potential of the internet to amplify the sharing of information about women’s lived experiences, as well as feminist activist voices. Above all, principle number 17 puts forward a call to end harassment and abuse of women in digital spaces (Feminist Internet, n.d.).

The principles offer a “gender and sexual rights lens on critical-internet related rights,” all of which are rights that exist in parallel in offline spaces. By building off the conceptual framework of a feminist internet, development organizations and NGOs can potentially enhance existing gender-transformative approaches to encompass the full picture of offline AND online gender-based violence that women face in the digital age.

Though I’ve argued earlier that the solutions proposed by the tech industry are limited and do not get at the root of the issue, we should not downplay the importance of their intervention. On this point the World Wide Web Foundation writes:

If companies can design solutions for the most marginalised women on their platforms, they will create a safer online experience for everyone (World Wide Web Foundation, 2021).

Efforts by the development community to support social norm change, coupled with an effort by tech industry leaders to enhance protection mechanisms for women using their platforms, makes for a holistic approach that has the potential to make the internet a safer place for the most marginalized, including women and female activists, and thereby, for all.

Conclusion and perspectives:

Through my previous posts in Talk Back, I have tried to contribute to discussions around what it means to be an activist in digital spaces, looking through a fairly techno-optimistic lens at how people define activism and build activist identities through online interactions. In this final post, though, I wanted to take a more critical stance, looking at the ways in which digital media enables not only activists, but also those who seek to silence activist voices, particularly those of women.

In total I contributed three individual posts to Talk Back, and in reflecting on each post, I’ve noted some key takeaway points, particularly in terms of the dichotomy of how offline structures influence online interactions and vice versa. In particular, I noted:

- How blurred the lines are between what is and is not activism in online spaces, as messaging on social justice issues permeates all corners of the internet, social media and online communities;

- How interactions in online spaces can influence and help to form a person’s offline activist identity;

- And on the other hand, how offline power relations influence interactions in online spaces, often to the detriment of women or other individuals with intersectional identities.

From a practical perspective, developing this blog with my other group members was an interesting practical exercise in engaging with and participating in discussions and debate on social media. This took me out of my comfort zone, and also gave me a great appreciation for the extensive amount of work that goes into content creation across different social media platforms.

Bibliography

- Amnesty International. (2018). Toxic Twitter: A Toxic Place for Women. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/research/2018/03/online-violence-against-women-chapter-1

- Catcalls of NYC [@catcallsofnyc]. (n.d.). [Instagram Profile]. Instagram. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://www.instagram.com/catcallsofnyc/

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021, March 1). The Social-Ecological Model: A Framework for Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/about/social-ecologicalmodel.html

- Chalk Back (n.d.). Retrieved 15 October 2021, from https://www.chalkback.org.

- Chalk Back [@chalkbackorg]. (n.d.). [Instagram Profile]. Instagram. Retrieved October 10, 2021, from https://www.instagram.com/chalkbackorg/

- Chalk Back [@chalkbackorg]. (2021, November 3). Happy Birthday Sophie! [Video]. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/p/CVyGI4tsbR7/

- Feminist Internet. (n.d.) Principles. Retrieved 10 October 2021 from, https://feministinternet.org/en/principles

- Feminist Internet. (n.d.) About. Retrieved 10 October 2021 from, https://feministinternet.org/en/about

- Hirsch, A. [@theaudacity]. (2021, September 30). How to Be a Woman On the Internet [Newsletter]. Substack. https://audacity.substack.com/p/how-to-be-a-woman-on-the-internet

- Lewis, R., Rowe, M., & Wiper, C. (2017). Online abuse of feminists as an emerging form of violence against women and girls. The British Journal of Criminology, 57(6), 1462-1481.

- The Economist Intelligence Unit. (2021, March 1). Measuring the prevalence of online violence against women. https://onlineviolencewomen.eiu.com

- Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas – The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Yale University Press.

- UNICEF (n.d.). Technical note on gender-transformative approaches in the Global Programme to End Child Marriage Phase II: A summary for practitioners. https://www.unicef.org/media/58196/file

- UN Women. (n.d.). Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimation Against Women: General recommendations made by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. Retrieved 15 October 2021, from https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/cedaw/recommendations/recomm.htm

- Vogel, E. (2021, January 13). The State of Online Harassment. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/

- World Wide Web Foundation (n.d.). Tech Policy Design Lab: Online Gender-Based Violence and Abuse. Retrieved 16 October 2021, from https://ogbv.webfoundation.org

- World Wide Web Foundation. (2021, July 1). Facebook, Google, TikTok and Twitter make unprecedented commitments to tackle the abuse of women on their platforms. https://webfoundation.org/2021/07/generation-equality-commitments/

- World Wide Web Foundation. (2021, July 1). “Prioritise the safety of women”: Open letter to CEOs of Facebook, Google, TikTok & Twitter. https://webfoundation.org/2021/07/generation-equality-letter/

- World Wide Web Foundation. (2021). Tech Policy Design Lab: Online Gender-Based Violence and Abuse Outcomes & Recommendations https://uploads-ssl.webflow.com/61557f76c8a63ae527a819e6/61557f76c8a63a65a6a81adc_OGBV_Report_June2021.pdf

![“How to be a woman [and activist] on the internet…”](https://wpmu.mau.se/nmict21group6/wp-content/uploads/sites/55/2021/11/Screen-Shot-2021-11-07-at-8.37.21-PM.png)

![“How to be a woman [and activist] on the internet…”](https://wpmu.mau.se/nmict21group6/wp-content/uploads/sites/55/2021/11/Screen-Shot-2021-11-07-at-8.37.21-PM-430x350.png)