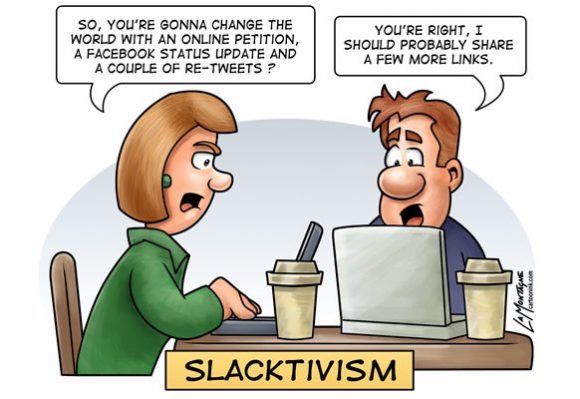

Critics call online activists “lazy,” others praise the online forum as an effective message-carrier. But can we really draw one line for how online activism is operated globally? And can an increasingly digitally-first society force activism upon its participants to the point where it no longer becomes effective?

Let’s talk about ‘Slacktivism’ for a moment. If you haven’t caught up with the term, your “any day” Jesse Brown shares his two cents to bring you up to speed.

Born a late-Millennial, I do in many ways pronounce myself guilty of ‘Slacktivism’. I might have shied away from the #JeSuisCharlie + French flag profile update on Facebook a few years back, but I sure have lectured my fellow online peers about the Refugee Crisis by sharing news posts or horrifying imagery on my feed; I’ve used hashtags to forward the #MeToo movement, and posted a Black square in contribution to the BlackLivesMatter ditto – not only in support of good causes, but because it was just commonplace, wasn’t it?

Quite frankly, there’s a lot to ‘Slacktivism’ – my minor contributions included – that can be attributed to positive change. While activism on the streets may be regarded as “preaching to the choir” in the eyes of some, hashtags and social media attraction is a strong vessel for raising awareness and spreading the word to a new audience. If activism is indeed about opening dialogue and influencing opinion, digitally is the quickest way to town.

Social media has in many ways morphed into a digital space for inspirational learning and storytelling. Fundraisers, petitions… simply gaining support for a cause, albeit temporarily, has arguably never been easier. Sure, one needs to battle through a constant flow of information overload but many cases of impactful change, like Greta Thunberg’s climate strike, can be attributed to a spark by social media movements.

We often judge slacktivism in a Western-centric light, as something that plays out in western democratic societies, when in fact online activism differs greatly in other parts of the globe. For example, in India, WhatsApp is said to be the most influential platform for mobilizing people for a cause. It has become known as a tool to counter inaccurate or politically-imposed information by allowing users to ‘forward’ such information to the masses. As Rutvi Zamre writes, “While it may not promote a strong sense of collectivism … social media is absolutely instrumental in removing barriers to credibility and allowing greater access to information.”

A recent study echoes that micro-level evidence supports a positive relationship between online activism and offline protest among citizens under repressive regimes. It can help mobilize minority groups, and stir up movements to expose or even end unfair treatment.

As with anything on the Internet, however, it becomes increasingly difficult to navigate misinformation and (conscious as well as systemic) confirmation bias when we are seasoned with information online that is in line with our beliefs and worldview. What’s more – especially fueled by the covid pandemic – the significance of online action is primary, and there’s a fine line between genuine engagement and mandatory public caring.

On the one hand, silence is compliance. Meanwhile, our social platforms facilitate this virtual ‘bar-hopping’ – giving us sips of new trends before we’ve gotten a chance to get drunk on any meaningful topic. We become reactionary activists, rather than being solution-minded.

Social media also has a “flattening effect” by forcing users to package their activism up stylishly to reach the masses. This, in effect, hinders proper context. While in one sense the audience and reach is easily targeted on such platforms, their structure is paradoxical to that of activist organizing. Basically, you have a vertically aligned platform that lacks key tools, has built in incentives and sanctions that condition users towards the status quo – and algorithms favoring content that makes users at ease over content that should make them feel distressed.

As Ella Glover puts it, “… the way online activism has morphed into an increasingly self-righteous, guilt-tripping black hole is pushing people to perform activism online, often to the detriment of their own mental health and seemingly less often to the benefit of a single cause.”

So how do you juggle virtuality and easy-to-join ‘slacktivism’ with a biased and antithetical online platform constantly guiding you onto the next trend? Is there more than one right form of activism across the board? And where do you view yourself in this mess?