Since the beginning of the twenty-first century, there has been an exponential rise in the spread of information technology worldwide, and consequently, a corresponding globalisation of data analytics. In this period, digital technologies have become available to populations that were previously digitally invisible, and many stakeholders are taking advantage of what the UN has termed the ‘data revolution’ (United Nations, 2014). In 2000, only 4 percent of people living in low- and middle-income countries had access to mobile phones, which had risen to a massive 94 percent by 2015. Such increased availability of digital devices is indicative of significant economic, technological, and human development. The availability of data emitted as a by-product of the public’s use of technological devices and services has both political and practical implications for the way the public is seen and treated by the state and by the private sector, at a global level (Taylor, 2017). The countries of the Global South, far from being decolonized, can be considered to have become subjected to the whims of international technology companies, where personal data is used to enhance their innovations, entrench their economic and political might, and in effect, occupy the daily lives of billions of people under ‘digital colonialism’. This brings us to the crucial question of what happens when the ‘2.0’ digital world meets the ‘1.5’ world of development projects?

Technology for the masses

This widespread use of mobile technologies has provided an unrivalled opportunity to boost economic, health, educational, and technological development (Pramanik, 2017). Hence, the increased prevalence of technology brings many benefits to countries in the Global South, with a considerable focus on digital solutions to humanitarian problems, in the realm of development practice. There have been myriad applications and systems developed to enable health professionals to provide healthcare and diagnostic services over the phone, particularly in rural communities with limited access to healthcare. Likewise, education and literacy are ever-present goals in the Global South, which have the potential to be realised with the use of mobile technologies. Technology has also helped Ethiopian farmers to crowdsource data to forecast and yield better crops. Birhane (2019) outlines that by revealing pervasive gender disparities in key positions, data can help bring the disparities to the fore and further support social and structural reforms. Hence, data can help bridge the huge inequalities that plague every social, political, and economic sphere. However, such initiatives cannot be delivered without access to the Internet, and accordingly, significant plans are in place to continue strengthening Internet connections across the continent of Africa.

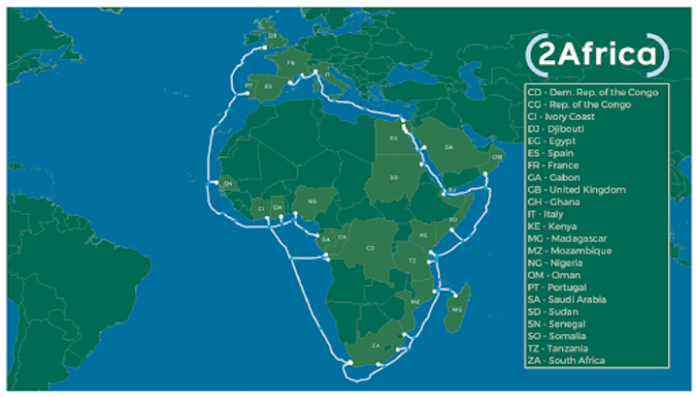

On 21 September this year, Facebook, in partnership with Vodafone, Orange, MTN, and China Mobile, announced its intention to build an Internet cable surrounding the African continent, bringing the Internet to millions of people. According to the announcement,

“Africa is currently the least connected continent, with only a quarter of its 1.3 billion people connected to the Internet. With 2Africa, we had planned to increase connectivity to 1.2 billion people. With the addition of ‘Pearls’, the system will provide connectivity to an additional 1.8 billion people, totalling 3 billion people, or about 36 percent of the global population. In its entirety, 2Africa will significantly increase connectivity within Africa and better connect the African continent to the rest of the world, as it will ultimately interconnect 33 countries in Africa, the Middle East, and Europe.”

In a blog, Mark Zuckerberg asserts that “connectivity is a human right”, affirming Facebook’s commitment to delivering universal connectivity. The United Nations has signalled agreement. Zuckerburg, amongst others, point to the importance of the internet for economic growth in Africa. Likewise, an RTI report showed that between 2008-2014 an increase in Internet connectivity via subsea cables in Kenya helped to boost employment, including increasing the proportion of higher ‘skilled’ jobs. Hence, there are significant plans coming to the fore to vastly increase Internet access across the continent.

Could it be too good to be true?

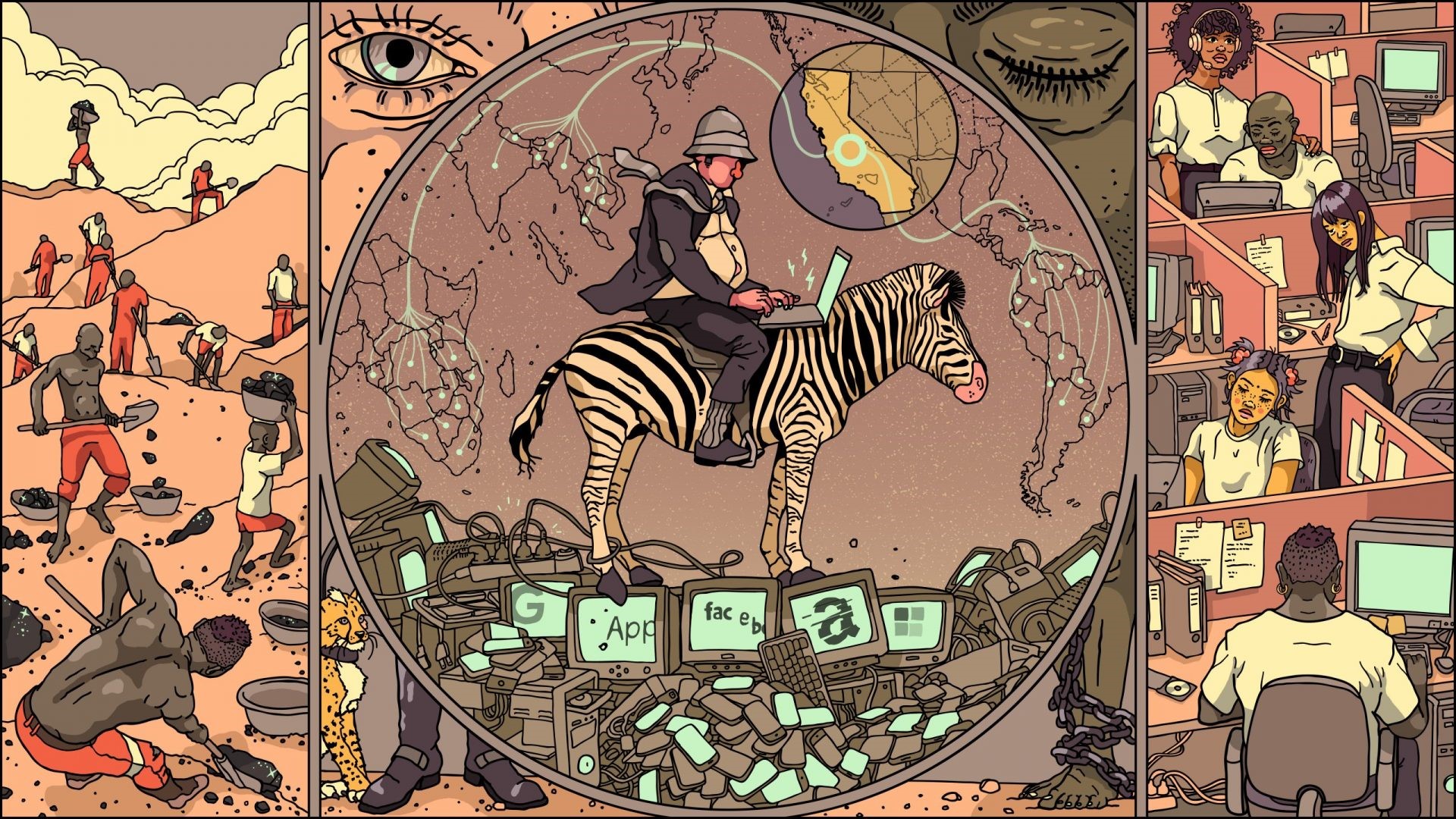

This exponential growth in access to digital technologies clearly brings a world of opportunity, but concurrently brings questions about data protection, data inequality, and the economic beneficiaries of the data economy. There are also concerns about hate speech on social media and the extent to which it fuels ethnic and religious tensions on the African continent. As the access to digital technology, and the Internet, typically comes courtesy of private corporations that capture and control user data, we can draw comparisons to the colonial powers who disguised the “Scramble for Africa” as liberalisation intended to help the “noble savage” (Coleman, 2019). International technology companies claim that they want to bridge the digital divide and give Internet access to the millions of people who otherwise would not have it. However, their true purpose is simply to extract data for profit and predictive analytics. Thus, companies have begun to look to the African continent, where an untapped population of 1.3 billion represents new opportunities for expansion. Hence, technology companies such as Google and Facebook, mobile network operators, retailers, data brokers such as Experian and Equifax – and those who can afford the high purchasing cost, such as advertisers in the Global North, are the true beneficiaries of the data revolution (Hilbert, 2016).

Coupled with the considerable concern of data exploitation, there is also great apprehension regarding the spread of online hate speech, which could ignite existing ethnic and religious tensions. The Internet, with a proliferation of unchecked ‘fake news’ and hate speech, presents new opportunities to incite violence (van Niekerk and Maharaj, 2013). For example, my previous blog post highlights that in 2017, it became abundantly clear that Facebook was a catalyst for anti-Muslim sentiment in Myanmar, which subsequently translated into full-blown ethnic cleansing of the Rohingya. Similarly, as reported by the New York Times in the article Where Countries Are Tinderboxes and Facebook Is a Match, riots in early 2018 erupted as anti-Muslim anger was whipped up on social media, forcing the Sri Lankan government to impose a state of emergency and block access to Facebook. One must recognize that such trends may further emerge in African nations as the levels of access to the Internet, and indeed social media platforms, increase across the continent.

This problem is not an easy one to address, and Facebook as one of the most prolific platforms will struggle to monitor content in societies with pronounced linguistic diversity. This is particularly worrying in light of the recent testimony from Facebook whistle-blower, Frances Haugen, who shared a 2020 summary in the Washington Post detailing that, although the United States comprises less than 10 percent of Facebook’s daily users, the company’s budget to fight misinformation was heavily weighted toward America, where 84 percent of its “global remit/language coverage” was allocated. Just 16 percent was earmarked for the “Rest of World,” (Zakrzewski et all, 2021)

Why the demand for data?

Coleman (2019) highlights that international technology companies, such as Facebook and Google, are becoming increasingly reliant on extracting, analyzing, and selling user data for profit and market influence, by securing massive unexploited and under-regulated datasets to fuel digital advancement. For example, Artificial Intelligence (AI) capabilities – understand everything from shopping habits to future careers or propensity for criminality – will only ever be as good as the datasets that feed them. Hence, without diverse data sets, the ability to innovate and enhance existing AI functionalities is limited. In the Global North, such large-scale data harvesting has resulted in extensive data protection laws and regulations emerging to ensure ethical use of that data, with one of the most prominent regulations being the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) adopted in the European Union in 2016. On the contrary, one can observe that these same protections do not exist uniformly, with a particular gap emerging in the often resource-rich, infrastructure-poor countries of the Global South, where international technology companies are bolstering their presence (Coleman, 2019). It is against this backdrop, that a thirst for new data to keep the AI engine chugging, has transformed traditional colonialism into its latest form of ‘digital colonialism’.

From a quest for diamonds to a quest for data

Renata Avila (2018), a senior digital rights advisor of the World Wide Web Foundation defines digital colonialism as

“the new deployment of a quasi-imperial power over a vast number of people, without their explicit consent, manifested in rules, designs, languages, cultures and belief systems by a vastly dominant power.”

The concept of digital colonialism is further outlined by Coleman (2019) as “the decentralized extraction and control of communication networks developed and owned by tech companies”. It is within this framework that the African continent has become the epicentre of digital colonialism, with the largest number of least interconnected nations, most cultural, linguistic, and racial diversity, and limited data protection regulations. Moreover, international technology firms’ exploitation of this diversity, heralded under the guise of internet-for-all initiatives, may actually undermine the data sovereignty of African nations, and impede the ability to develop native digital economies. Such a situation is fraught with the danger of further exploitation of such nations under the facade of altruism. One can draw on an example from O’Donnell & Sweetman (2018), who highlight that only 0.7 percent of the world’s domain names are registered in sub-Saharan Africa. Moreover, we can compare this to traditional colonialist practices that seized raw materials from the African continent, refined and manufactured them into goods in the West, and sold these very goods back to the same nations from which they were stolen—leaving such nations unable to develop their own manufacturing capabilities (Elmi, 2020).

Birhane (2019) outlines that due to the inherently political nature in which data is construed, collected, and used to produce certain outcomes, aligning with those controlling and analyzing the data, such systems alter the social fabric, reinforce societal stereotypes, and further disadvantage those already at the bottom of the social hierarchy. This is evident in the practices of both Chinese and U.S. tech giants, who have been adopting a humanitarian agenda in the marketing of their respective digital infrastructure projects (Elmi, 2020). One can observe that Chinese corporations leverage political initiatives like Beijing’s controversial Belt and Road Initiative to secure contracts with African governments, whereby AI and other technology solutions are provided in exchange for access to local citizens’ data—like the deal between CloudWalk, a Chinese developer of facial recognition software, and the Zimbabwean government (Elmi, 2020). Western corporations, on the other hand, have been adopting a more covert approach, establishing digital hubs, and offering free Internet access in the form of the Free Basics initiative. One can infer that, as outlined by Manovich (2012), digital technologies sort people into ‘data-classes’, dependent on whether one collected or analysed big data, or whether one was simply a passive producer of it. Moreover, one could deduce that the Global South has become a sort of ‘digital proletariat’ that fuels big data analytics through their digital footprints (Manovich, 2012).

The need to regulate

Robert Kirkpatrick of the UN’s Global Pulse data science initiative has said that for citizens of the Global South that “privacy is your right”. As such, Taylor (2017) posits that just as an idea of justice is needed in order to establish the rule of law in nation-states, an idea of data justice is necessary to determine ethical paths through a datafying world. Mann (2016) outlines the explicit need to embed principles of justice in the way data markets are structured. Hence, the way in which data is processed and analysed within national and global data markets can often position individuals as subalterns in relation to those who process their data (Spivak, 1988). On this basis, Mann (2016) argues for the potential benefits to lower-income countries of collecting and analysing data independently of the large international technology firms, and on how such data’s returns can be captured and processed at the local level. It is within this context that some African governments are already trying to fight digital colonialism through regulation. To date, Nigeria, Rwanda, Kenya, and South Africa have advocated for data localization, which necessitates that all data collected on their citizens, and in their countries, be kept on servers where they are collected—rather than in California or Guangdong. This is a good and a forceful first step, but cross-border data flows are crucial to the modern economy—and data localization laws are generally short-sighted tools that can stifle, rather than foster, indigenous digital ecosystems (Elmi, 2020). Perhaps, as Elmi (2020) suggests a potential solution would be to develop a pan-African approach to cross-border data flows—possibly within the African Union—by understanding that data is a commodity worthy of protection at national and regional levels, and perhaps even under the African Continental Free Trade Agreement.

Conclusion

To conclude, it is clear that access to technology on one hand brings tremendous benefits to the Global South in terms of education, health, access to information, and economic growth, leading some to herald it a “human right”. However, on the other hand, it must be addressed that under the guise of altruism, large scale technology companies are using their oligopoly to gain access to untapped data with the potential to exploit such a resource for myriad reasons, leading some to consider that “data is the new oil”. Hence, digital colonialism is, at times, conflated with humanitarian efforts, as it is difficult to object to expanding digital access, which nearly all agree is crucial for economic growth and overall development. But corporations’ support for emerging economies may be a double-edged sword, as data extraction undermines the Global South’s abilities to develop indigenous digital economies that can enhance their own capabilities.

To answer the crucial question of what happens when the ‘2.0’ digital world meets the ‘1.5’ world of development projects, one could suggest that, on a theoretical level, a framework to reconcile the differing perspectives on the technological advancements, and indeed the ethical use of data, could be created. Firstly, it would need to take into account the complexity of the ways in which big data systems can discriminate, discipline, and control populations (Taylor, 2017). Secondly, it would have to offer a framing that could take into account both the positive and negative potential of the new data technologies – their ability to facilitate what Nussbaum and Sen (1993) term ‘human flourishing’, which forms the overall aim of human development – and also their potential to hinder it. Finally, it would have to be done using principles that were useful across social contexts, and thus remedy the developing double standard with regard to privacy and data exploitation in lower- to-middle income countries of the Global South (Taylor, 2017).

Reflections

I believe I have approached this assignment by applying a balanced viewpoint in conducting my research, while simultaneously incorporating a critical lens in assessing the literature and media coverage on relevant topics. The research carried out to frame each blog post has enabled me to deeply immerse myself in the facts, and not just personal impressions, which has resulted in a balanced summary of the promises and perils of technology at a global level.

The predominant theme running through my blog posts was the effect of social media, and indeed wider technological advancements, on our globalised world, with particular emphasis on the Global South. I began by highlighting that the web has made societies increasingly open and connected, while it has at the same time, significantly intensified instability, and fuelled tensions along social, political, and ethnic divides. Through my first blog post, I had the opportunity to outline the positives and negatives of social media, as well as posing questions, and providing potential solutions, on ways to address emerging issues. From this vantage point, I made a timely transition into analyzing the Senate committee testimony delivered by Facebook whistle-blower, Frances Haugen, in my post Is Facebook Prioritising Profit over Peace? Her testimony highlighted that performance metrics encouraged political divisions, violence, and in some cases civil unrest.

My first two articles formed the basis for my final (academic) post which analysed Technological advancements in the Global South and the rise of ‘Digital Colonialism’. It posits that access to technology has, on one hand, brought tremendous benefits to the Global South in terms of education, health, access to information, and economic growth. However, on the other hand, large-scale technology companies are using their power to gain access to untapped data with the potential to exploit such a resource for myriad reasons.

Over the course of the module, through my own writings and that of fellow group members, I have developed an expansive knowledge of a wide range of topics in the field of new media, ICT, and development, and have developed a deep interest in this field. Furthermore, this assignment provided me significant opportunity to further strengthen my WordPress and content management experience.

***This blog post has been updated since its original publication on 26 October 2021.

References:

Birhane, A. (2019). The Algorithmic Colonization of Africa Birhane. Real life Magazine. https://reallifemag.com/the-algorithmic-colonization-of-africa/ [Retrieved: 20 October 2021]

Coleman, D. (2019). Digital Colonialism: The 21st Century Scramble for Africa through the Extraction and Control of User Data and the Limitations of Data Protection Laws. 24 MICH. J. RACE & L. 417. Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mjrl/vol24/iss2/6

Cinnamon, J. (2020). Data inequalities and why they matter for development. Information Technology for Development. 26:2, 214-233, DOI:10.1080/02681102.2019.1650244

Elmi, N. (2020.) Is Big Tech Setting Africa Back?. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/11/11/is-big-tech-setting-africa-back/ [Retrieved: 19 October 2021]

Hawkins, A. (2018). Beijing’s Big Brother Tech Needs African Faces In Foreign Policy.

Internet Health Report. (2018). Resisting digital colonialism https://internethealthreport.org/2018/resisting-digital-colonialism/ [Retrieved: 19 October 2021]

Kwet, M. (2019) Digital colonialism: US empire and the New Imperialism in the Global South. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306396818823172

Mann, L. (2018). Left to other peoples’ devices? A political economy perspective on the big data revolution in development. Development and Change, 49(1), 3–36.

Manovich, L. (2012). Trending: The promises and the challenges of big social data. In M. K. Gold (Ed.), Debates in the digital humanities (pp. 460–475). Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press

Nussbaum, M.C. & Sen, A. (1993) The Quality of Life. WIDER Studies in Development Economics. Oxford: Clarendon Press Oxford.

Narayan, Pepper, Boakye & Tambeayuk. (2020). The economic impact of subsea cables in Africa. Facebook Engineering.

Nwokoma, C. (2020). How technology is helping African youths gain skills for employment and entrepreneurship. Techpoint. Africa. https://techpoint.africa/2021/07/15/technology-employment-entrepreneurship/

O’Donnell, A., & Sweetman, C. (2018). Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs. Gender & Development. 26:2, 217-229, DOI: 10.1080/13552074.2018.1489952

Pramanik et al. (2017). Big data analytics for security and criminal investigations https://doi.org/10.1002/widm.1208

RTI International. (2020). Analysis of the Economic Impact of Subsea Internet Cables in Sub-Saharan Africa

Salvadori, K. (2021). 2Africa Pearls subsea cable connects Africa, Europe, and Asia to bring affordable, high-speed internet to 3 billion people. Facebook Engineering.

Spivak GC. (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In: Nelson C and Grossberg L (eds) Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture. University of Illinois Press, pp. 271–313.

Solon, O. (2017). ‘It’s digital colonialism’: how Facebook’s free internet service has failed its users. The Guardian.

Taylor, L. (2016). No place to hide? The ethics and analytics of tracking mobility using mobile phone data. Environment and Planning: Society and Space, 34(2), 319–336.

Taylor, L. (2017). What is data justice? The case for connecting digital rights and freedoms globally. Big Data & Society, 4(2). doi:10.1177/2053951717736335

United Nations. (2014). A world that counts: Mobilising the data revolution for sustainable development. New York. Available at: http://www.undatarevolution.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/A-World-That-Counts2.pdf [accessed 9 October 2017].

van Niekerk, B & Maharaj, M. (2013). Social Media and Information Conflict. International Journal of Communication. 7. 1162–1184.

World Bank. (2016). Digital Dividends Overview. World Development Report. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/961621467994698644/pdf/102724-WDR-WDR2016Overview-ENGLISH-WebResBox-394840B-OUO-9.pdf

Zakrzewski, V & Mahtani (2021) How Facebook neglected the rest of the world, fueling hate speech and violence in India. The Washington Post.

Zuckerberg, M. (2013). Is Connectivity a Human Right? Retrieved October 30, 2021