As I travel across Ukraine guided by the news flowing form the messaging and local online channels, the most prominent example of where ICT contributes to a common good is the app Повітряна тривога (‘Air alert’), which warns the citizens of the upcoming shelling and missile strikes, or even chemical attacks, allowing people to seek shelter on time.

The app was introduced as early as 1 March, so just over a week after a fully-fledged conflict escalated in Ukraine, commissioned by the Ukrainian Ministry of Digital Transformation. It is available for free on Android and iOS systems, downloadable both from Apple and Google stores. Ajax Systems, which developed the technology, is one of Ukraine’s largest tech companies. As opposed to a range of other conflict and disaster settings, driven by foreign actors or international aid agencies coming up with solutions, the digital response in Ukraine at large is hugely characterised by local ownership.

Learn more: Sky News gives an interesting overview on how international big data companies reacted to the escalation.

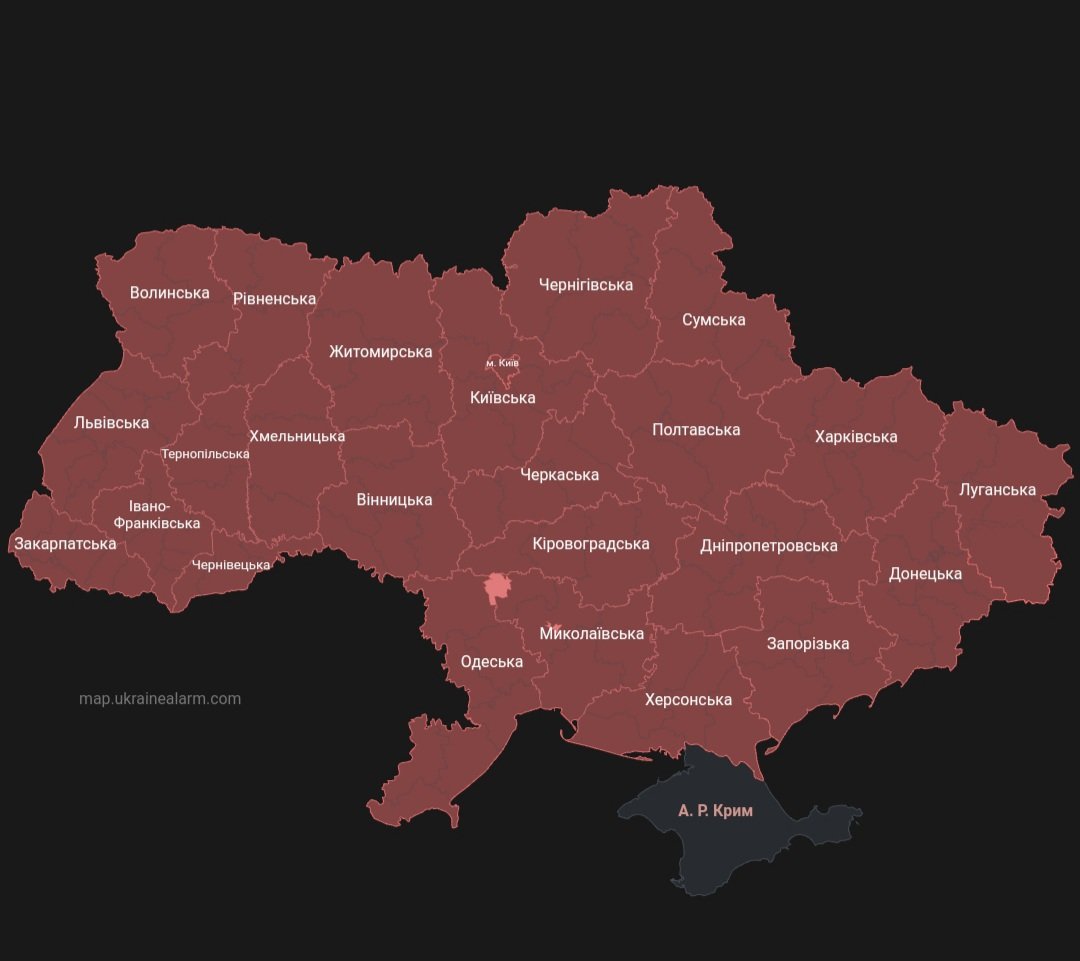

Trivoga, the new civilian defense system, shows alerts for the currently chosen region you need to set manually, but you can also see a current map for all the oblasts (‘regions’) and monitor the situation in the entire country. The application has adjustable settings – one might adjust the alerts to sound, vibrate or just switch them off. The app creators claim it is saving lives due to the swiftness of response – it notifies people on the upcoming attacks before the street sirens do. I have experienced it myself, particularly when in Dnipro, as there were good few minutes between the app warning of the air threats and the sound of sirens coming from outside.

The third, very long air raid alarm in #Vinnytsia sounding within the last 12 hours. The #Ukraine warning app shows the entire country is ordered to shelter at the moment – people say it has been unusual over the past few weeks. pic.twitter.com/HtA4r80KZ3

— Joanna Nahorska (@Joanna_Nahorska) October 10, 2022

Interestingly, this new development came at a time when Google decided to stop sharing the live traffic data and information on how busy places get to protect people fleeing Ukraine en masse, or secure busy places from being targets, highlighting the importance of ethics and security linked to using ICT systems in humanitarian emergencies. Sky News also reports that “in Ukraine the company has updated its Search and Maps services to provide alerts to UN resources for people searching for refugee and asylum information.”

Learn more: If you wish to get a global overview including a range of interesting Ukraine resources, Data-Pop Alliance offers an interesting insight into new technology in humanitarian emergencies.

The app generates a loud alert warning of an airstrike, chemical attack, technological catastrophe or other types of civil defence alerts. Air Alert is the only application supporting critical alerts among similar ones. It means that notifications are delivered even in the smartphone’s silent or sleep mode. The app notifications duplicate civil defence sirens in cities, so please consider their signals when reacting to the app notifications. The Air Alert app is an additional tool, not a primary civil defence alerts source.

Source: Ajax Systems website

As autonomous digitalization in Ukraine continues despite of the months of escalated violence, with the new banking apps popping up for cash assistance and Trivoga continuing to sound a couple of times per day and night, warning systems are not a new thing in humanitarian response.

Early warning systems have been historically used in conflict prevention and save lives – this Word Bank blog provides a really good overview of the existing mechanisms – and are widely embedded in peacebuilding, with the UN at the forefront of an ICT4Peace project. In his Peace insight article, Schields analyses the use of early warning systems for peace: “Information and communications technologies (ICTs) and mobile phones in particular can be an aid in early warning and violence prevention at the local level, where both the knowledge and the desire to prevent violence are available.”

If we apply his thinking that violence is the outcome of the lack of information, whereas “mobile phones can play a critical role in helping people share information that can defuse violence before it starts” to the Ukraine context, the app created by Ajax indeed is a great example of lifesaving technology. It helps to monitor potential lethal situations and to employ a push alert to protect civilians.

The evolution of ICT today provides the governments, civil society and (I)NGOs with an unprecedented possibility to detect, monitor and respond to crises. What is missing in the discussion, however, is the ethical responsibility of consumers at the receiving end of the technological advancements. In Ukraine, a few decide to take shelter these days. People tell me that if they were to respond to each and single time their phone buzzes, day and night, they would not be able to function anymore. This leads to bizarre images, where in a fancy café full of people everyone suddenly grabs their smartphone to silence an alert notification – and consciously chooses to ignore it. There is only as much as technology can do when the collective responsibility for own safety is vanishing – and where people just wish to live their lives in a conflict situation of a cognitive dissonance.

Can you think of any other digital response system employed so rapidly – and at such a large scale?