With the current uprise in misogyny and the lack of adequate responsibility taken by social media platforms to regulate its harmful content, the future looks dire for women.

Platforms have increasingly been moving towards using AI and machine learning for the reviewing of content, this especially since the pandemic showed the need for businesses to have digital resilience. These technologies created are designed, trained and formed primarily by men in the global north and naturally it answers unequally to the needs and wants of people. According to the World Economic Forum, only 22% of AI professionals and 12% of researchers in the machine learning and AI field globally are women. It can be argued that women are hit on three different fronts:

- Globally women’s have less access to ICT’s than men.

- The design process gravely lacks the representation of women.

- Gender-based violence online is not being taken seriously by decision-makers.

Now, it is worth noticing that the issues listed are far more complex than a binary analysis of gender, can explain. Gender intersects with social class, ethnicity and other categories of exclusion, which cannot be ignored in the analysis. Also, there are great disparities globally in the situations and circumstances. That being said and taken into account, I still argue through a gender lens in this paper (O’Donnell & Sweetman, 2018).

“Technology mirrors the societies that create it, and access to (and effective use of) technologies is affected by intersecting spectrums of exclusion including gender, ethnicity, age, social class, geography, and disability” (O’Donnell & Sweetman, 2018)

Dhanaraj Thakur, in his article on the issues regarding gender-based violence online, explains how new forms of violence, unique to the online sphere, has emerged (e.g., revenge porn). The online space has the potential to increase control of and surveillance of its victims, while anonymity is kept and empathy is reduced. This online violence in turn incites to violence offline. Some examples are stalking, trolling, invasion of privacy. Young women are especially targeted with online sexual harassment, and the level of reporting is low. Thakur especially underlines the lack of awareness and acknowledgement of online gender-based violence as a problem (O’Donnell & Sweetman, 2018).

But the issue goes beyond. Women politicians, journalists and other women who take up public activities or activities which implies public exposure, are experiencing very worrying amounts of gender-based violence and orchestrated disinformation campaigns. In responding to this, they are the ones required to protect themselves through reporting, blocking, muting, deleting and restricting the attacks. This puts an immense pressure on the victims. According to a survey done by UNESCO on women journalists, 41% of respondents said they had been targeted in online attacks appearing to have been orchestrated disinformation campaigns. This was also confirmed by UNESCOs big data case studies (UNESCO, 2021).

When women are threatened as a part of their participation in the public debate, this can be a factor of discouragement for them to undertake such activities at all. This in itself is a threat to society and democracy. Social media platforms have failed to respond adequately to the risks and dangers of violence and gendered disinformation, that women experience in the digital space. Actually, the platforms’ business models and biased algorithms work strictly against tackling gendered disinformation, as they build on engagement and popularity. According to social media companies, one of the challenges is finding the balance between freedom of expression and hate speech. Other challenges include insufficient fact-checking, context-blind AI tools and the influence of governments. COVID-19 exacerbated the difficulties and the urgency to address the issues.

Promising commitments or victim blaming?

Big Tech companies supposedly made promising commitments at the Generation Equality Forum 2021. At the Forum, hosted by UN Women, Meta (then Facebook), Twitter, Google and TikTok committed to improve reporting systems and ways for women to take control of their safety online. The commitments and the proposed solutions to address online gender-based violence took basis in recommendations made by the Web Foundation’s tech policy. This happened through the hosting of a Policy Design Lab with intentions to co-create solutions to online gender-based violence.

Specifically, they offered a more granular setting for women to avoid seeing sexist comments, given them more control over who can interact with posts. Additionally, they also proposed a more accessible and easy language in the user experience, making it easier to apply the safety tools. These pledges were in no way attempting to address the core issues and systemic nature of gender-based violence online. Rather, it suggests masking women from seeing the abuse, they still receive, and enabling them to resolve their own abuse problem. Also, suggesting that making the user experience easier, downright sends a disrespectful and victim-blaming message. It is not because women do not know how to report, block or silence abuse that they are victims of it. Many women already use these functions, and it is nowhere near fair or effective. If one person receives daily abuse in the thousands, or if a woman politician is being targeted in orchestrated disinformation campaigns, which is spread at incredible speed, how are these women supposed to surmount this?

These commitments were heavily criticized by 37 women’s rights organisations, through a letter addressing the CEOs of Meta (then Facebook), Twitter, Google and TikTok. The signatories claim the ordeal is nothing but a feel-good PR stunt and that the platforms are part of the problem. The also highlight that it essentially is like asking women to “cover up”.

Introducing Safety Mode on Twitter

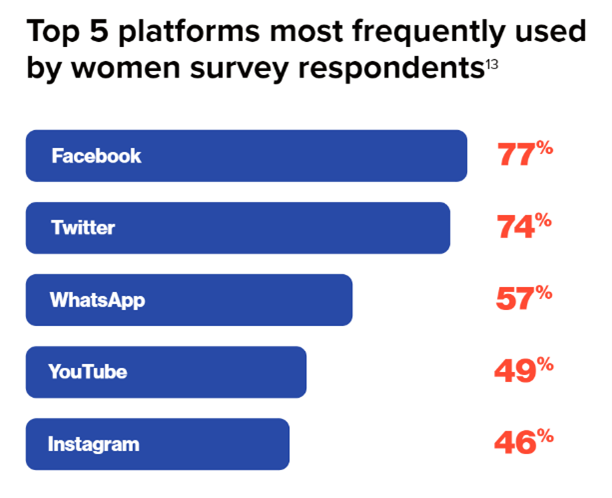

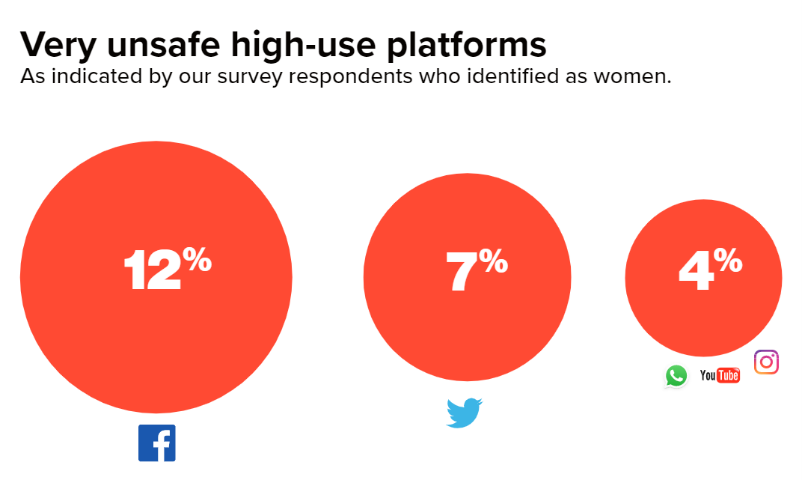

According to a survey done by UNESCO on women journalists, Facebook followed by Twitter was rated the least safe platforms by respondents. 26% of the survey respondents reported online attacks. The main complaint being that when reports are made on the platforms, the platforms fail to adequately enforce their own rules (UNESCO, 2021).

As an example of the outcome of Generation Equality, Twitter introduced Safety Mode. This feature, when turned on, can temporarily block accounts, assessing the probability of negative engagement. You can also manually review the blocked accounts and comments, to assess the decisions made by the feature. This does in a way alleviate the pressure on women themselves to do the reporting, blocking etc. This seems to be a (baby) step in the right direction. But what do high-profile women using this feature say? And what will happen now that Elon Musk has acquired the platform?

The case of Nina Jankowicz

In 2020, when Nina Jankowicz published her book How to Lose the Information War: Russia, Fake News, and the Future of Conflict, she became a target of online abuse and harassment, primarily gendered. In her book, she wrote about the Russia’s online warfare against democracy, the rise of disinformation and misinformation. Jankowicz has also advised governments on the information war. The abuse intensified when she took the position as Executive Director of the United States Department of Homeland Security’s Disinformation Governance Board, a new board created by the Biden administration. She left her position only after one month due to the immense abuse directed at her and the controversy around the board. It eventually was dismantled. In April 2022, she published How to Be a Woman Online: Surviving Abuse and Harassment, and How to Fight Back, recounting the unlimited amount of gender-based violence women in politics, journalism, and academia face online. Drawing on research along with her own lived experience, she proposes a step-by-step guide for women to navigate gendered abuse in the online sphere.

Nina Jankowicz recounts her abuse being present in her everyday life, even as an expert on the matter. She also recounts, that it has affected her physical well-being and blood-pressure, as she was pregnant at the height of the ordeal. According to Jankowicz, a lot of it is highly coordinated, making it against the terms of service of platforms. But often the platforms are too slow and relying on the individual to take action. When dealing with large campaigns, very little is done as the platforms lack the capacity and political will to act.

“I have now blocked 300,000 people on Twitter, and the platform is only just starting to become somewhat usable for me again…The platform allows you to use Safety Mode, which shows you only reputable replies, and then along with Block Party, which in addition to blocking people auto-mutes certain mentions using AI, I really don’t see as much as I used to. I also have friends who are helping me comb through mentions to look for direct threats, which are still coming in. But it’s sad that I have to kind of go to such great lengths to even use and maintain my presence on the platform” (Nina Jankowicz, 2022).

Twitter after Elon Musk

On Twitter, we are yet to know what’s the future holds after its acquisition by Elon Musk. So far, we have heard that verified users might have to pay a monthly fee for their badge. New intel from employees report that Twitter is holding back staff’s ability to counter misinformation leading up to the US midterm election. This regards the Trust and Safety organization particularly. In addition to dealing with the safety feature mentioned above, it deals with ‘high-profile violations’, the type of violations that is are not outsourced to contractors nor automated by AI. Since Musk’s takeover, several media outlets have reported on sudden upswing in hate speech. Musk calls himself a free-speech absolutist and is adamant that Twitter is too restrictive, for instance regarding misinformation and hateful conduction policies. More precisely, employees report that Musk wants to either rewrite or remove the section of hateful conduction policies that penalizes users for “targeted misgendering or deadnaming of transgender individuals”.

We must keep an eye on what’s to come, but in regard to the fight against gender-based violence and disinformation online, this unfortunately does nothing but heighten concerns.

Going forward

Platforms very much symptom treats this epidemic. Existing reporting systems put the responsibility of action on the victim’s shoulders, and this benefits the platforms in multiple ways. Firstly, it shifts the burden of responsibility and potentially saves lots of money for the platforms. Instead, this should be invested in researching and designing sustainable solutions. Secondly, it enables the platforms to continue benefiting from the harmful content and disinformation, which feeds into their business model. All in all, it is a win-win situation for the companies, if they manage to get away with these types of low effort commitments and do a bit of publicity damage-control at the same time.

Social media platforms should work towards providing sustainable solutions to address the fundamental causes of online gender-based violence. There needs to be both preventative measures and strict regulations put in place. There should be heavy investment in the development of context-sensitive technology. Gendered disinformation campaigns are systematic and widespread. They require attention from the international community. Governments as well as traditional media, human rights and civil society organisations are key stakeholders that should take action to require social media companies to put measures in place. Notably through design- and implementation strategies tackling gendered disinformation. In addition, there should be wider awareness on this issue. It is crucial that women are not left behind in ICT’s. Women should be equitably represented in the various technology fields, from education to decision making positions in both research and design.

Concluding reflections on the blog experience…

This blog exercise has been a steep learning curve and a look into what the blogosphere has to offer. It allowed me to dive into a subject that I work with on a daily basis through the lens of our theme: social media, datafication and development. Blogging is an interesting way to work with knowledge management and networking and once the technical aspects and time management is down, it goes smoother. It is also a way for those working in places that require secrecy, to share their views on topics they work with. Unfortunately, this also complicates the promotion of the blog and the use of personal social media to do so. Our choice to simulate social media for various reasons, has in turn led to an interesting discussion and further reflection on how to work around these issues in the future.

References:

- Amy O’Donnell & Caroline Sweetman (2018) Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs, Gender & Development, 26:2, 217-229, DOI: 10.1080/13552074.2018.1489952

- UNESCO, Julie Posetti, Nabeelah Shabbir, Diana Maynard, Kalina Bontcheva Nermine Aboulez (2021) The Chilling: global trends in online violence against women journalists; research discussion paper – UNESCO Digital Library

- How to Be a Woman Online: Surviving Abuse and Harassment, and How to Fight Back: Nina Jankowicz: Bloomsbury Academic