In August 2022, Education Cannot Wait, the United Nations global fund for education in emergencies and protracted crises, published its annual report titled “We have promises to keep. And miles to go before we sleep” to present results achieved in the year 2021. Under the section “Access and Continuity” at page 101 the report analyses the Distance Learning Program. I will use this section of the report to further explore distance learning as a tool for development, particularly in the East Africa Region. I’m invested in this topic and interested in your thoughts and opinions. Let’s meet afterwards in the comment section below and have a discussion.

But before we start: is the internet accessible in East Africa?

I think it’s crucial to have a general understanding of internet connectivity in East Africa and access to digital devices before getting too far into the discussion. The short answer to the question above is: to a very limited extent. We will consider Uganda as an example. Together with Kenya, Tanzania, Burundi, Rwanda, Congo and South Sudan, Uganda is one of the seven countries that compose the East African Community. .

Uganda population is 74.77 million of whom 73.9% are living in rural areas, where the access to electricity is 10%. The Ugandan population is also one of the youngest in the world with an average age of 17.2 and in January 2022 the country counted 13.92 millions of internet users. Internet users in Uganda increased by 1.8 million (15.1%) between 2021 and 2022 but at 4.54Mbps, the internet connection speed is 40 times lower than the average internet speed in Europe. Social media users registered in 2022 was equivalent to 5.9 percent of the total population and 57.9% of the population have a mobile connection.

Distance Learning for Development?

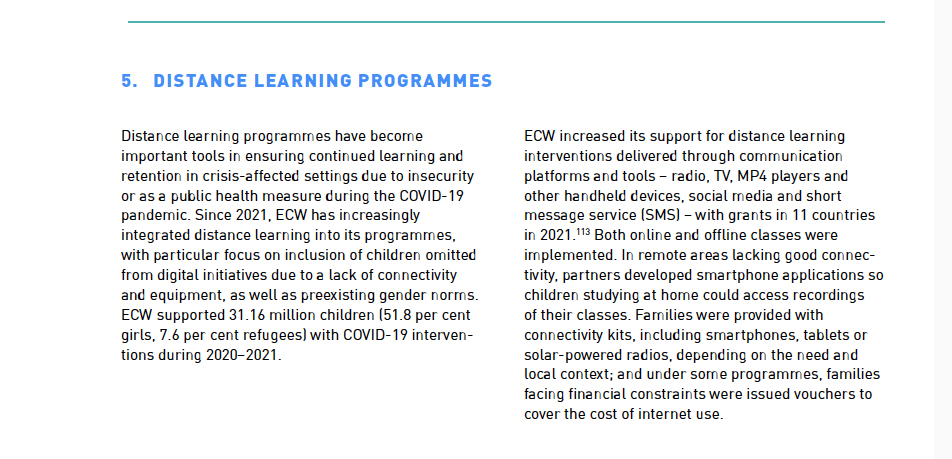

The premise of the introductory line of the chapter on distance learning is that e-learning, and by extension, the devices and internet connection, are a tool for development. Because technology increases access to education and hence fosters development, it is assumed that it cannot have any adverse impacts. But are we certain that this presumption is accurate?

ICTs undoubtedly have the potential to reduce poverty, for example by enhancing education, health delivery, rural development, and entrepreneurship across Africa, Asia, and Latin America. However, all too often, projects designed to do so fail to go to scale, and are unsustainable when donor funding ceases. – Tim Unwin

Tim Unwin in his book Reclaiming Information and Communication Technologies for Development introduces an interesting point: sustainability. How sustainable are these interventions if only 10% of the population living in rural areas of Uganda has access to electricity? For how long will ECW provide vouchers to parents to process internet bundles? And what will happen when the devices distributed will break?

Unwin also invites to reflect on the interests of connecting millions of people to the internet and how for decades technologies have been regarded too optimistically. They have been seen as an instrument for positive change, although the reality is that the spreading of ICTs (such as mobile devices and social media) has usually been associated with increasing inequality. In this regard the World Bank in 2016 reported that the benefit of the digital economy has been less than expected and has not been equally distributed. But Unwin further emphasizes the underlying importance of using ICTs to change the social and political structures that create poverty.

Instead of ICTs for Development (ICT4D) we have become increasingly and surreptitiously enmeshed in a world of Development for ICTs (D4ICT), where governments, the private sector, and civil society are all tending to use the idea of ‘development’ to promote their own ICT interests.

Technology has always been used to serve a particular purpose, and ICTs, especially in developing countries, are majorly considered as a positive progressive process for social change, often ignoring the interests behind it. My question remains: how sure can we be that providing access to internet and digital devices to millions of students, especially those in rural areas, will not enhance inequalities?

Is distance learning safe?

On page 102 under “Lesson Learnt” the document reports:

Distance learning programmes were introduced as an innovative solution during and after COVID-19-related school closures. Such programmes, however, needed to adapt to local contexts, address a range of connectivity needs, consider the pre-existing gender digital divide, as well as online safety concerns, and adjust approaches to mitigate the greater risk of learning loss among marginalized children.

My main concern is safety. Does ECW invest in procedures that ensure the security of the students they are directly and indirectly enrolling online? What steps are being taken to reduce the risks (data properties, sexual exploitation via the internet, child protection issues etc.) when attempts are made to create an equitable education system in developing countries? Who are the stakeholders involved in ensuring safety and which interests they have in this regard? Will the technologies used to reach the most marginalized be able to address their vulnerabilities?

Amy O’Donnell and Caroline Sweeteman, dedicated part of their work to the theme of Gender and Development and better express some of the risks that characterized online spaces:

Online spaces offer the potential to develop new forms of violence, curbing freedom of expression in a very gendered way. They can lead to physical violence too. Multiple identities – including gender, race, and class – are all critical factors responsible for limiting who has access to digital in a given context. We need to ask questions about policy, culture, power and capabilities, with a gender and intersectionality lens.

What do you think?

These are just a few of the thoughts that came to mind as I read the report; there are certainly many more, such as parental involvement in online education or the importance of developing basic literacy skills, but I think these are sufficient to reflect on the risks and opportunities of ICTs. Please share your thoughts with me.

Reference:

DataReportal.2022 Digital 2022:Uganda [Online]. [Accessed 22 Ocotber 2022]. Available from: https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-uganda?rq=Uganda

2018: Introduction: Gender, development and ICTsLinks to an external site., Gender & Development.

Unwin, T. 2017: Reclaiming Information & Communication Technologies for DevelopmentLinks to an external site.. Oxford: Oxford University Press.