Introduction

Today, there are more than 6.64 billion smartphone users, 650 million of whom reside in Africa. In 2021, 111.3 billion downloads from Google Play and 32.3 billion downloads from iOS were recorded. Thus, the question arises: can mobile phones and the services made available through them, such as telephone applications, assist in reducing inequality and poverty?

An optimistic vision of technology, that saw its application as an all-too-simple solution to many of the issues facing developing countries, such as access to education, healthcare, or market opportunities, predominated for many years. But with the experience, we have now, since the first telephone application store was launched by Steve Jobs in 2007, can telephone applications truly be seen as a tool capable of delivering development to the peripheries of society and enhancing the lives of those who are most vulnerable? If true, what risks are associated with this technology?

This essay tries to assess the potential and threats that telephone applications and their usage for development represent by looking at different perspectives, including those of end users, software developers, and tech companies. The study, which focuses on the advantages and disadvantages of these three subjects, aims to encourage reflection on the fact that technology is not neutral and, as a result, on the precarious and frequently unbalanced power relationships that exist between the various characters that drive the digitalization of developing countries.

Inclusiveness or Marginalization of end-users?

Potentials of new information and communication technologies (ICTs) have been underlined in several publications in the past years, scholars, and researchers have proved the ICT’s ability to make the world better, and to reduce poverty.

In this regard, I provide the perspective of Uwe Deichmann and Deepak Mishra who, while acknowledging the great benefits of technology, concentrate on those who are still without access to computers and mobile phones and, consequently, on the disparities that they produce:

Research in West Africa showed how simple information technologies improved learning, reduced producer price uncertainty, and generated time savings for poor farmers. Yet, there is reason to believe that these benefits have not had the massive impact on poverty reduction that many expected. Even though more people in developing countries have access to a mobile phone than to electricity or safe water and sanitation in their homes, most of the poor still do not own a mobile phone or computer. Rather than being a great equalizer, digital technologies risk amplifying existing inequalities. (Graham, 2019)

Their opinion is supplemented by Tim Unwin’s book titled A Critical Reection on ICTs and ‘Development’ in which he argues:

ICTs have played a crucial role in driving such economic growth, but they also have a darker side, not least in creating greaterinequalities through the considerabledifferential access to them that exists both spatially and socially across the world.(Unwin, 2017)

To strive to create a more equitable world, it appears that today’s issue is to lessen disparities between those who have access to modern technologies and those who do not. How can the divide be bridged and a collaboration between governments, companies, and other stakeholders been made to contribute to the genuine development?

The critical engagement of end-users is another factor that is sometimes overlooked by the positive narrative of technology use. How aware are the people who use applications on a regular basis in their daily lives? To be more explicit: is the Kenyan farmer using iCow (a mobile phone based agricultural information platform for small holder farmers) to forecast the stages of his farm’s gestation aware that access the app means giving the app’s owner his personal information?

Abeba Birhane regarding data collection argues:

Data and AI seem to provide quick solutions to complex social problems. And this is exactly where problems arise. Around the world, AI technologies are gradually being integrated into decision-making processes in such areas as insurance, mobile banking, health care and education services. And from all around the African continent, various startups are emerging — e.g. Printivo in Nigeria, Mydawa in Kenya — with the aim of developing the next “cutting edge” app, tool, or system. They collect as much data as possible to analyze, infer and deduce the various behaviors and habits of “users.” (Birhane, 2018)

At this point I would like to highlight the contentious relationship between empowerment of marginalized communities, that is often touted as an advantage of ICT given that rural communities now have access to tools to make user voices heard, and data exploitation, which is frequently accompanied by violations of people’s privacy and other rights on the part of technologies companies creating the same instruments.

In the South, the majority of the people are essentially stuck with low-level feature phones or smartphones with little data to spare. As a result, many millions of people experience platforms like Facebook as “the internet,” and data about them is consumed by foreign imperialists. (Kwet, 2021)

Can we honestly claim that ICTs are employed for the betterment of disadvantaged and vulnerable people in light of so-called data mining, the near lack of policies protecting safety, individual rights, and freedom, and the consequent power in decision-making of the corporate world?

Who is creating mobile apps, and what is their purpose?

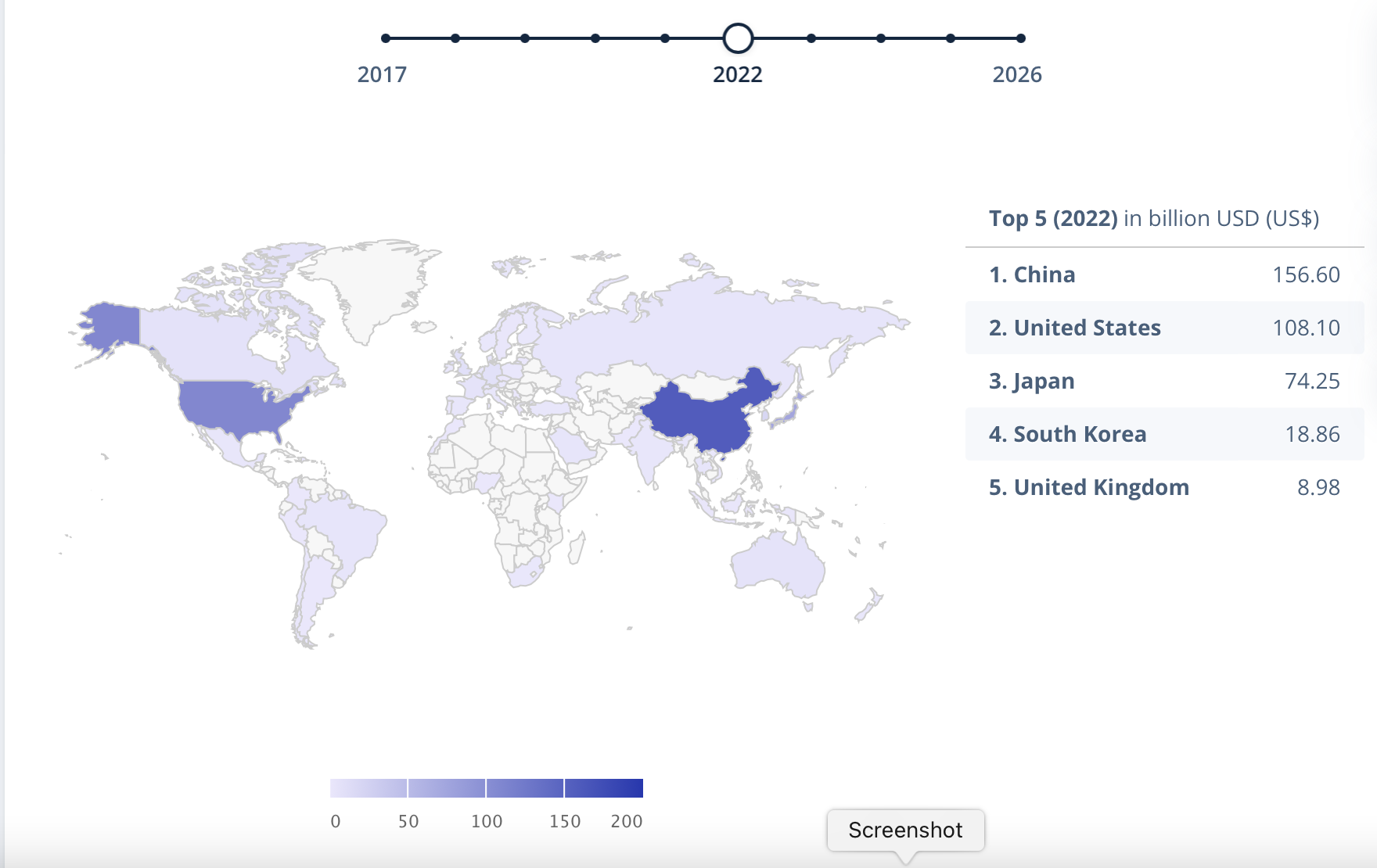

Total revenue in the app market is projected to reach US$868.60m and the end of 2022; who is behind it and with which scope? Key players of the mobile application market include Apple Inc., Google LLC, Microsoft Corporation, Netflix Inc are majorly operated in North America, making the region dominating the mobile application market with a share of 31,83% in 2021.

The market’s fragmentation and the existence of mobile application developers in emerging nations like Kenya, South Africa, and others are also depicted in the map (fig.1) below.

But before deep in that I would like to draw attention to the design and development stage of the mobile applications creation process and emphasize how frequently answers to problems in developing countries are defined in the Northern part of the world.

Therefore, the idea of critical engagement, which was previously mentioned, goes beyond awareness of the effects of app usage to include end users’ involvement in the design process. A critical engaged end user should be able to identify the issues they would like to have addressed through the creation of mobile applications.

Companies frequently respond to this complaint by citing the participative method concept, which is valid in and of itself and gains relevance when applied to the many stages of developing a mobile application, including problem identification, solution development, product design, and testing.

Unfortunately, the participatory method and the resulting improvement in the usage of the product are more valuable to the companies that developed the app than they are to end users, despite their active engagement. This is because the participatory technique is typically only used to teach end users how to use the app.

Participatory methods have often been perceived as a means to address power inequalities within technology design in developing countries. However, such methods sought to balance power inequities within one (predominately Western) culture, which poses a problem when design groups and users belong to different cultural contexts. (Bentley, Namer, Vannini, 2017)

On the other hand, the expanding digital sector presents a growth potential for many developing nations, bringing up new markets and even job opportunities in the sector.

However, as reported by Graham when discussing the digitalization of Kenya, the African country is still very far from securing the benefits of this technological revolution because it is not yet active in manufacturing products.

The promise, however, is misplaced because the mobile revolution has hardly been a stimulus for economic inclusion via industrial expansion. Africa still lags behind other regions of the world in manufacturing, and it has not made major steps to move to the production of mobile-related technologies. (Graham, 2019)

In the same chapter, Graham examines the optimism surrounding the rising number of technology hub in African urban regions, which are becoming a representation of the entrepreneurial spirit of African youth. Graham emphasizes the necessity to incorporate the expertise of these hubs in a larger ecosystem of innovation and does not stop at stressing the good features, such as the fact that Africans themselves think about and discuss solutions to their problems:

Their appearance away from centres of research and learning also signals the need to foster more integrated innovation ecosystems that bring business, academia, and government together. The hubs have also exposed the need to improve the overall funding and policy environment for technology-based ventures. The definition of mobile inclusion in Africa needs to broaden to cover industrial development. This includes the potential to manufacture devices, equipment, and infrastructure components. It also entails strengthening human capacity in the related engineering fields. (Graham, 2019)

The case of mobile application developers in developing contexts seems to imply, as in the analysis of the potential and risks for end-users, that there are still many threads to be untangled before this industry can be declared to be dedicated to the improvement of the lives of the most disadvantaged populations. This is since ostentatious optimism related with technologies is not always a reliable predictor of reality and frequently minimizes the challenges and concerns.

The case of iCow mobile app to manage herds in East Africa

Mobile phones have trans-formed East Africa in the last 15 years, not just seen from a social and cultural point of view, but access to and use of mobile phones and applications is also shaking up the region’s entire economic system.

Jan Embro, President of Ericsson in sub-Saharan Africa and representing one of the leading infrastructure suppliers in East Africa believes that:

“Mobile communication significantly improves quality of life, providing the tools to deliver enormous socio-economic benefits to people in developing countries. Connectivity helps to offset a lack of resources, particularly in rural areas, and provides access to a range of services, includiing education and healthcare” (Ericsson 2008).

2010 saw the launch of iCow in Kenya, and that same year, it won the first Apps4Africa 2010 competition by transforming an IVR-based program that only allowed farmers to control the gestation calendars of their animals into an SMS-based version with expert search functionality.

Its growth continued, and now, owing to the relationship with Safaricom, iCow is a tech company with a workforce of more than ten employees and coverage that extends to the entire African continent. With more than 110 million educational SMS delivered, iCow’s comprehensive ecosystem of digital services and solutions has reached 1.6 million farmers.

The motto used to introduce the app to potential users, “We are farmers for farmers”, tries to highlight its capacity to address the actual needs of the farmers.

While this is undoubtedly true for the Kenyan setting, where the application gained traction thanks to the effort of its founder Su Kahumbu Stephanou, who also spent his formative years on a Kenyan farm, we cannot make the same claim for realities that differ from to Kenyan ones.

Personally, I think that iCow’s early success was largely due to its capacity to meet the special needs of Kenyan farmers and its deep understanding of the surrounding environment, both of which allowed it to design a highly functional application.

So, if the application is demand-driven and culturally suitable in the Kenyan setting, can we claim the same for the rest of Africa? I doubt about the application’s adaptability to different contexts, and I wonder if it actually has international advantages or if it is simply one of many apps that are downloaded in other countries but don’t actually provide a real change or tangible solution for community members.

The application’s success was further aided by the usage of voice messaging and local languages, two features intended to solve the literacy issue. In fact, the following was considered to get beyond the main obstacle of illiteracy: farmers receive a series of voice notes and SMS messages about their cow’s nutrition, health and disease, vaccinations, milk cleanliness, and milking techniques throughout the cow cycle. How many different languages and dialects are there on the African continent, I wonder?

In conclusion, the use of iCow has increased farmers’ revenue and productivity throughout various African locations, but it has also demonstrably changed the lives of Kenyan farmers because their communities are more aware of and involved with the application.

Conclusion

In the world of aid and cooperation, mobile applications continue to be popular. Major donors and private foundations choose to develop mobile applications to guarantee access to health care, rather than market opportunities or education, for millions of people who still live on the margins of society due to social or geographic factors.

By analyzing the concerns of two parties (end users and developers), this post sought to depart from the idealistic and oversimplified view of the mobile application for inclusion and equality and instead highlight the challenges and concerns that mobile applications today face, with a particular emphasis on the non-neutrality of technology and the power dynamics that exist between the parties. I have been able to argue the effectiveness of mobile apps as a tool for development precisely because of the analysis of power relations, which has allowed me to better comprehend reality, interests, and the practical space for change.

The case study has also supported the analysis of the theoretical ideas covered in the preceding paragraph. As a result, it has brought to light the importance of awareness and engagement of end users to bring social change and that efficiency of technology is guarantee if the tools are demand-driven and culturally appropriate.

Reflections

This post is a part of a larger exercise that examines the power dynamics surrounding the use of ICTs for development in the AID sector. Together with Nina, Sylvia, Zahra, Eman, and myself, we all published blog articles to address the topic.

The blog writing exercise allowed me to explore a new topic (ICT4) and also improved my understanding of the technical aspects of online writing, including its potential and limitations, the value of establishing a target audience and a brand identity, the strength of the digital ecosystem that connects various channels and tracks flows, the rapid evolution of digital tools, and finally the steps for setting up a blog.

I believe that the acquisition of knowledge both at a theoretical level of the opportunities and risks of ICTs, and at a practical level in the management of the blog, has made me more aware of the contents that I consume online but also of the contents that I publish as an individual or on behalf of international organization I work for.

Bibliography

Bentley, C.M., Nemer, D. & Vannini, S. 2019: “When words become unclear”: unmasking ICT through visual methodologies in participatory ICT4D. AI & Society, 34,477–493.

Birhane, A. 2019: The Algorithmic Colonization of Africa.Real Life Mag, 9 July.

Graham, M. (ed.) 2019: Digital Economies at Global Margins. Ottawa, ON/Boston, MA: IDRC/MIT Press.

Kwet, M. 2021: Digital colonialism: the evolution of American empire. ROAR, 3 March.

Unwin, T. 2017: Reclaiming Information & Communication Technologies for Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.