The last decades have been marked by an unprecedented technological explosion, where the digitalisation of society has increased prosperity, and global population is living on average longer and under better conditions. In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic that caused significant disruptions to livelihoods, persistent inequalities that were already on a rising trend have further worsened (Harries, n.d.; Tay et al., 2022).

At the same time, this conjuncture has accelerated the digital transformation, boosting the digitising of diverse areas, ranging from education, heath, commerce, to financial services, etc. The potential of Information and Communication Technologies (ICTs) to reduce inequalities and fight poverty has been officially recognized by United Nations and has long been widely debated (Lechman & Popowska, 2022). But are ICTs really a driver of equality? This article aims to reflect and analyse the impact of ICTs, in particular of digital financial inclusion, in achieving development goals.

Are ICTs contributing to poverty alleviation?

There are multiple opportunities offered by ICTs for the developing world, being looked at “as a source of socio-economic transformation by enhancing growth of social and economic networks, accessing knowledge and information, new services, and employment growth” (Lechman & Popowska, 2022, p. 2). According to Steinberg (2003), ICTs are a very attractive element of any development strategy because of their ability to transcend geographic barriers, their potential to reap the benefits of scale, and to facilitate wide-ranging know-how transfer.

Technology is said to reduce the impediments to growth and fostering inclusion for the disadvantaged and the underprivileged (Bisht & Mishra, 2016), being considered among the greatest enablers of improved quality of living (Toyama, 2011). It is possible to find several examples of successful ICT4D1 (ICT for Development) projects that seem to push through arguments for digital development at global margins, tracing connections between technological advancements and improved access to information, education, health, economic activities, labour, government, financial services, among others (Lechman & Popowska, 2022; Mushtaq & Bruneau, 2019; Unwin, 2019).

In addition, several authors argue that ICTs are also powerful tools to boost socio-economic development, increasing social cohesion and empowerment, allowing income generation and enhancing economic growth (Adera et al., 2014; Dominguez Castillo et al., 2018; Unwin, 2017). Since the notion of economic growth is still foundational to the understanding of development (Heeks, 2017), the economic benefits associated with technological advances have made them very popular in the field, to some authors the most optimal mean of achieving welfare (Andreev et al., 2019).

But this is not a consensual understanding. Despite all the optimism surrounding the technological transformation of the lives of those who can access, afford, and use ICTs, the ones excluded become even more disadvantaged than they were previously (Unwin, 2019). As argued by Toyama (2012), this digital divide happens through differential access, capacity, and motivation – the most privileged have greater access to technology, have distinct education, social skills and connections, and are driven by unlike motivations.

In this context, more balanced views emerge and institutions like The World Bank (2016) acknowledge that “the effect of technology on global productivity, expansion of opportunity for the poor and the middle class, and the spread of accountable governance has so far been less than expected” (p. 2). On a more critical note, Unwin (2017) suggests that increased worldwide inequities are rooted in the design of ICTs and their rapid deployment, and in the linkage between ICTs and understanding of development as economic growth, focused on delivering its hegemonic agenda. The author further argues that the idea of ‘development’ itself served to promote technological interests of the private sector, but also governments, and civil society, in what he incisively defines as a self-serving ‘Development for ICTs’ (D4ICT) — not only failing to fulfil the technological potential but negatively impacting the poor and marginalized (Unwin, 2017, 2019).

The literature shows even more critical voices to the view of technology as a magic bullet for developing counties (Deichmann & Mishra, 2019). This criticism finds ground in clear and extensive evidence of ICT4D projects’ failures. There are several reasons mentioned, including the use of top-down and non-participatory approaches that fail to involve the stakeholders and keep them engaged, a tendency to focus first on the most extreme examples of underdevelopment, unfavourable legal and institutional environments, rigidity in project delivery and ineffective project leadership, and failure to learn. There are also other factors, such as the inadequacy of the technology to the context, unsustainable and unviable financial models, non-scalability, disregard for poor infrastructure or unintended uses of technology, lack of skilled workers for maintenance and training, etc. (Heeks, 2011, 2017; Kirkman, 1999; Lechman & Popowska, 2022; Steinberg, 2003; Toyama, 2011, 2012; Unwin, 2019; Walton & Heeks, 2011; Weigel & Waldburger, 2004).

The detrimental effects of technologies are noted in different contexts and at different levels. There are records of violence or harassment against women enabled for or related to ICTs, along with male control (Heeks, 2017); reduced employment opportunities and pressure on low-skill occupations due to widespread automation (Deichmann & Mishra, 2019); or the expansion of marginal livelihoods created in the black or grey digital economy, such as gambling, cybersex, click-farming, scamming, blackmailing, etc. (Heeks, 2017).

In addition, ICT penetration is proven to negatively impact households that channel a greater portion of their limited budgets on technological goods and services, instead of using them to meet other basic needs, such as food, health or education (Mushtaq & Bruneau, 2019). The matter of opportunity costs also affects high-level decision-making, where there may be pressure to divert funds from budgets intended for non-technological purposes (Toyama, 2012). Besides, the use of technology raises further concerns related to privacy issues and surveillance by corporations or governments – for social protection, to maintain control or exert influence (Unwin, 2017), deep thinking erosion (Toyama, 2015), dissemination of fake information, increased anxiety, depression, and other disorders, reduced productivity, or exposure to fraud, scams or malicious content (Mushtaq & Bruneau, 2019).

Adding a new layer to this discussion, some authors regard the pervasive and implicit instrumentalist view in theory and practice in ICT4D as fundamentally problematic (Unwin, 2017, pp. 23–24). Nevertheless, technology is never neutral (Green, 2002), it is developed to reach specific goals and serve particular interests, and it is imbued with social, economic, cultural, and political value (MacKenzie & Wajcman, 1999), and once created it may deviate from the original purpose or end up achieving unexpected results (Unwin, 2017). Thus, digital divide should not be seen as the root cause but rather as a symptom of poverty and inequality, and technology can at best be adopted as a tool to achieve development goals, not being a solution in itself (Adera et al., 2014; Kirkman, 1999).

Image: Mounou Désiré Koffi (Ivory Coast). Le Wotrotigui. 2020. [source]

Digital financial inclusion

After a brief overview of different discourses around the use of ICTs to tackle inequalities, we will now focus on a particular sector where technology has fostered worldwide changes, and, according to many, is lifting people out of poverty: the financial sector.

According to Bisht and Mishra (2016), inclusive growth is a key priority of policy-makers in both the developing and the developed worlds, positioning financial services as one of the fundamental services to achieve this, contributing to a more just and more equitable society. Given the foundational role of finance in any transaction/exchange, these services are classified as having the potential to bring about change and transformation, “increasing opportunities, reducing poverty, enhancing well-being and growth” (Bisht & Mishra, 2016, p. 818).

In this area too, technology has brought drastic changes, expanding financial inclusion through digitalization. Digital financial inclusion can help mitigate economic and social impacts of the pandemic, contributing to a more inclusive financial recovery (Tay et al., 2022). A study by Mushtaq and Bruneau (2019) shows a negative relationship between ICT diffusion and poverty, suggesting that most ICT indicators can assist in reducing poverty and decreasing income inequality through the promotion of financial inclusion. Evidence support that financial services driven by technology lead to greater access to the unbanked in many Asian and African countries, having the potential of bringing access to financially excluded populations worldwide (Bisht & Mishra, 2016).

As mentioned by Heeks (2017), financial lives of the poor have high relative transaction costs, risks and uncertainty, and digital financial services are “helping to reduce those costs, increase the security of their financial transactions, and smooth out some of the financial volatilities they face” (p. 256). Karombo (2022) also contends that these services helped to overcome some challenges that excluded the poor, namely illiteracy, lack of money, lack of documentation and distance to traditional banks.

Across the globe, it is possible to observe several examples of technology-driven initiatives in the domain of financial services, such as ATM machines, internet banking, the use of mobile technology, smart cards, or point of service devices (Bisht & Mishra, 2016). Mobile phone penetration in particular is said to promote financial inclusion in lower and middle-income countries, mainly because of the dissemination of mobile money (m-money) services (Mushtaq & Bruneau, 2019).

The Global Findex Database 2021 shows that, in the last decade, account ownership in developing countries has risen from 42 to 71 percent of adults, against 76 percent globally. Also, the gender gap in access to finance has fallen from 9 to 6 percent (Malpass, 2022). An account is an empowerment tool, allowing for secure transactions, facilitating savings and access to money, enabling their holders to start or grow businesses, and boosting productivity. For women, it presents extra benefits to move into electronic transactions, allowing them to avoid money appropriation by other household members, increasing productivity and agency (Grown, 2015). Notwithstanding the promising growth in account ownership and use, only 55 percent of adults in developing economies were able to access extra funds within 30 days to meet their needs, and about two thirds showed concern about at least one area of financial stress (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022).

Mobile money technology was a driver of account ownership and usage, becoming a relevant enabler of financial inclusion in Sub Saharian Africa (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022). Yet, a pernicious effect arising from the massification of mobile finance is currently being observed, possibly undermining the long-term goal of improving financial inclusion. Some governments – in Ghana, Zimbabwe, Uganda, etc. – are looking at this industry as a way to broaden their tax bases and target the informal economy, introducing new taxes over digital payments that may push the lower-income and rural communities back out from the financial system (Karombo, 2022).

Encouraging trends and results are emerging. The usage of digital payments in developing countries increased from 35 percent in 2014 to 57 percent in 2021 – while in high-income economies is almost universal, and a significant share of 39 percent of m-money account holders in Sub-Saharan Africa are using the account to save. Furthermore, evidence demonstrates that receiving payments such as salaries and government support directly into an account can help achieve development goals (Demirgüç-Kunt et al., 2022).

Malpass (2022) refers that the digital revolution is also a powerful tool to improve governance, allowing direct transfers to social programs’ beneficiaries, reducing leakage and delays, also increasing transparency and reducing the scope for corruption. Also, The World Bank’s leader advocates for decisive action to further support this transformation: the creation of an enabling policy environment, the promotion of the digitalization of payments, and emphasizing access for women and the poor.

Nevertheless, the formal financial sector in most parts of Africa is still very exclusive, despite all digital technologies, and in developing countries large segments of the population are still excluded (Kouladoum et al., 2022). Furthermore, the introduction of technology in financial markets rendered the products and services more complex, and limited financial literacy among poor households may hinder the digital financial inclusion (Heeks, 2017; Mushtaq & Bruneau, 2019).

Despite the speculation and optimism about the role of ICTs on financial inclusion, Kouladoum (2022) warns that there is still a lot to be determined in the African continent. Moreover, he suggests that digital technologies have not yet fully succeeded in contributing to sustainable development due to high illiteracy rates, and technological infrastructures and services costs (Kouladoum et al., 2022).

As financial technologies demonstrate, successful technology-enabled development interventions cannot be scaled simply by scaling technology (Toyama, 2011). While digital technologies have promoted growth, widened opportunities, and improved service delivery, their aggregate impact has lagged behind and is unevenly distributed (World Bank, 2016). Multidimensional investments need to be made to overcome wide-ranging and long-standing obstacles, and to increase the digital dividends — the broader development benefits facilitated by digital technologies — fostering enabling environments, building strong human and institutional capacity, increasing imperative regulatory frameworks, improving public sector’s accountability, among others (Deichmann & Mishra, 2019).

It is undoubtedly hard not to be dazzled by the technological potential and encouraging results around the world. But what we take away from this analysis is that technology should only be seen as just another tool and not an end in itself, otherwise it may contribute to exacerbating already existing inequalities and further harm the most vulnerable populations. If we accept technological progress as a panacea, disregarding the actual impact on vulnerable populations and not taking action to mitigate the risks and overcome obstacles, we may exacerbate inequalities and get stuck in the cycle of “pin[ning] our hopes on the next new shiny gadget” (Toyama, 2012, p. 11).

Wordcount: 2255

Notes:

[1] While the use of this terminology (ICT4D) is widely debated (Roberts, 2019), for the sake of simplicity and because this discussion is beyond the scope of this article, we will adopt this term.

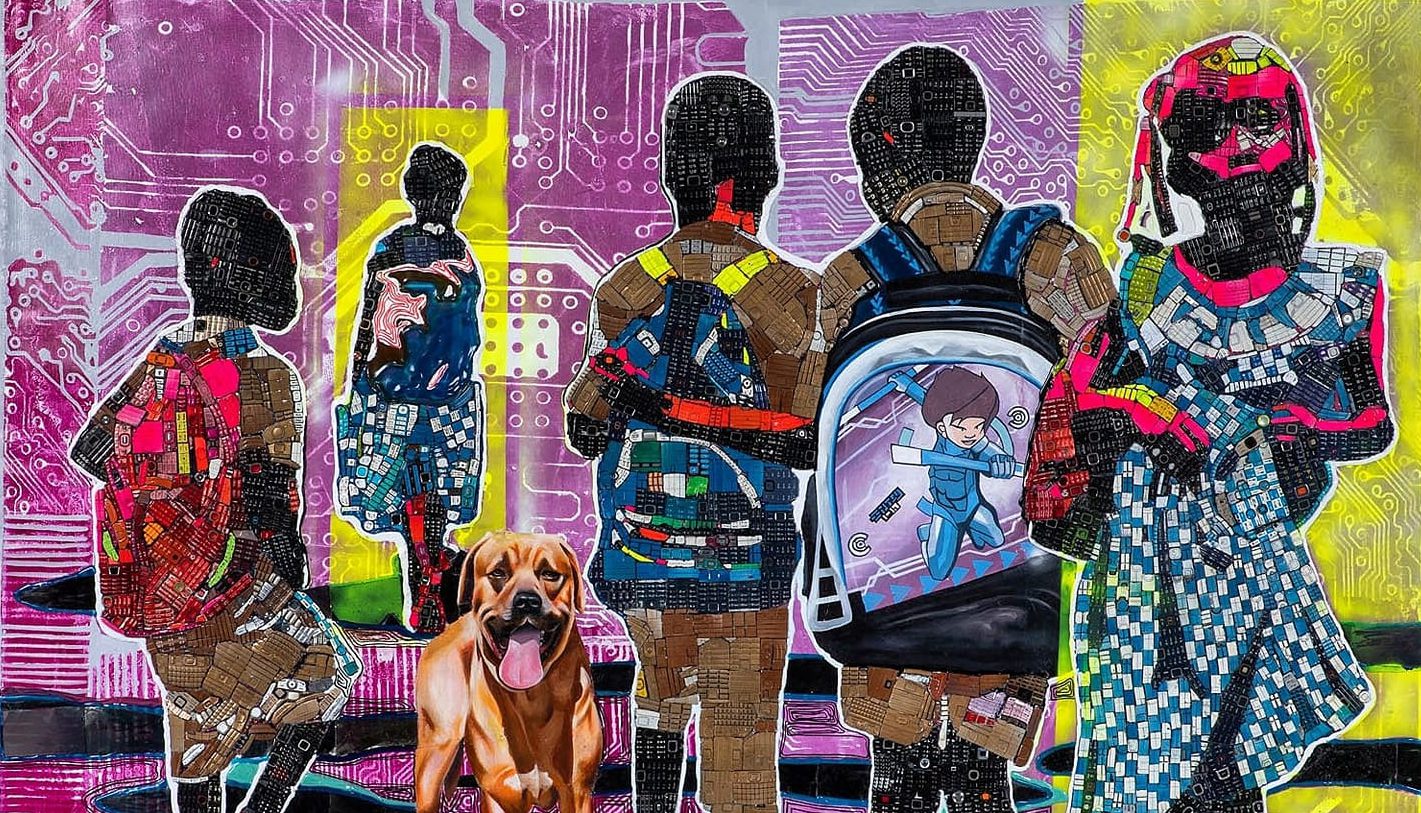

* Featured image: Mounou Désiré Koffi (Ivory Coast). Untitled, 2020. [source]

References:

Adera, E. O., Waema, T. M., May, J., Mascarenhas, O., & Diga, K. (Eds.). (2014). ICT pathways to poverty reduction: Empirical evidence from East and Southern Africa. Practical Action Publishing.

Andreev, O., Grebenkina, S., Lipatov, A., Aleksandrova, A., & Stepanova, D. (2019). Modern information technology development trends in the global economy and the economies of developing countries. Revista Espacios, 40(42).

Bisht, S. S., & Mishra, V. (2016). ICT-driven financial inclusion initiatives for urban poor in a developing economy: Implications for public policy. Behaviour & Information Technology, 35(10), 817–832. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2016.1183711

Deichmann, U., & Mishra, D. (2019). Marginal Benefits at the Global Margins: The Unfulfilled Potential of Digital Technologies. In M. Graham (Ed.), Digital economies at global margins (pp. 21–24). The MIT Press.

Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Klapper, L., Singer, D., & Ansar, S. (2022). The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1897-4

Dominguez Castillo, J. G., Cisneros Cohernour, E. J., & Barberà, E. (2018). Factors influencing technology use by Mayan women in the digital age. Gender, Technology and Development, 22(3), 185–204.

Green, L. R. (2002). Technoculture: From alphabet to cybersex.

Grown, C. (2015, November 20). Both Feet Forward: Putting a Gender Lens on Finance and Markets. World Bank Blogs. https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/both-feet-forward-putting-gender-lens-finance-and-markets-mobile-banking-movable-collateral

Harries, D. (n.d.). Innovation: Can technology beat poverty? 2. Retrieved September 25, 2022, from https://stories.cgtneurope.tv/hubs/innovation-action-change/can-technology-end-poverty/index.html

Heeks, R. (2011). Can a Process Approach Improve ICT4D Project Success? ICTs for Development. https://ict4dblog.wordpress.com/2011/11/29/can-a-process-approach-improve-ict4d-project-success/

Heeks, R. (2017). Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D) (1st ed.). Routledge.

Karombo, T. (2022, July 1). “It’s a lazy tax”: Why African governments’ obsession with mobile money could backfire. https://restofworld.org/2022/how-mobile-money-became-the-new-cash-cow-for-african-governments-but-at-a-cost/

Kirkman, G. (1999). It’s More Than Just Being Connected. Development E-Commerce Workshop.

Kouladoum, J.-C., Wirajing, M. A. K., & Nchofoung, T. N. (2022). Digital technologies and financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommunications Policy, 46(9), 102387. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2022.102387

Lechman, E., & Popowska, M. (2022). Harnessing digital technologies for poverty reduction. Evidence for low-income and lower-middle income countries. Telecommunications Policy, 46(6), 102313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.telpol.2022.102313

MacKenzie, D., & Wajcman, J. (1999). The social shaping of technology. Open university press.

Malpass, D. (2022). Foreword. In A. Demirgüç-Kunt, L. Klapper, D. Singer, & S. Ansar, The Global Findex Database 2021: Financial Inclusion, Digital Payments, and Resilience in the Age of COVID-19. The World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1897-4

Mushtaq, R., & Bruneau, C. (2019). Microfinance, financial inclusion and ICT: Implications for poverty and inequality. Technology in Society, 59, 101154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2019.101154

Roberts, T. (2019, September 9). Digital Development: What’s in a name? Appropriating Technology. http://www.appropriatingtechnology.org/?q=node/302

Steinberg, J. (2003). Information Technology and Development: Beyond Either/Or””. Brookings, 7. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/information-technology-and-development-beyond-eitheror/

Tay, L.-Y., Tai, H.-T., & Tan, G.-S. (2022). Digital financial inclusion: A gateway to sustainable development. Heliyon, 8(6), e09766. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09766

Toyama, K. (2011). Technology as amplifier in international development. Proceedings of the 2011 IConference, 75–82. https://doi.org/10.1145/1940761.1940772

Toyama, K. (2012). Can Technology End Poverty? Boston Review. https://bostonreview.net/forum/can-technology-end-poverty/

Toyama, K. (2015). Geek heresy: Rescuing social change from the cult of technology. PublicAffairs.

Unwin, T. (2017). Reclaiming Information and Communication Technologies for Development (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198795292.001.0001

Unwin, T. (2019). Digital Economies at Global Margins: A Warning from the Dark Side. In M. Graham (Ed.), Digital economies at global margins (pp. 43–46). The MIT Press.

Walton, M., & Heeks, R. (2011). Can a Process Approach Improve ICT4D Project Success? SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3477344

Weigel, G., & Waldburger, D. (2004). ICT4D, connecting people for a better world: Lessons, innovations and perspectives of information and communication technologies in development. Swiss Agency for Development and Cooperation, Global Knowledge Partnership.

World Bank. (2016). World Development Report 2016 (p. 359). International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank.