My first two blog posts focused on issues of communication, particularly how subjects such as extreme poverty and conflicts are framed within the media and what wider consequences that can lead to. I also tried to highlight the decreasing development aid around the world and the significance of that for countries in dire need of assistance.

This finale blog post, on the other hand, will discuss the concept of ’effective altruism’, short EA, both as philosophy and social movement. As we have seen within my previous blog posts, international humanitarian aid is being cut by several governments around the world, making the issue of using existing aid most effectively more pressing than ever.

Philanthropy in global development

Over the past few years, official aid flows to non-profits and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) have decreased considerably (Osili et al. 2020). While the civic space has become more and more under pressure (United Nations – OHCHR), resulting in decreasing aid flows in countries that increase restrictions on NGOs; the COVID-19 pandemic and the ongoing conflict in the Ukraine led governments to cut and/or redirect their money to ‘more pressing’ areas. – Just recently, Sweden announced its radical shift in foreign aid, explaining that it will use the aid cuts amounting to 9.8 billion Swedish kronor to finance the reception of asylum seekers instead (United Nations, 2022).

Although there is a negative impact on funding from official donors, cross-border philanthropic giving to NGOs steadily increased over the last two decades. In 2018 alone, the flow of private cross-border resources (philanthropy, remittances, and private capital investments) were almost four times the amount of official development assistance (Osili et al. 2020).

Considering then that resources are scarce and that a lot of the charitable giving is driven by individual private donors, while taking into account the cheer number of NGOs and INGOs in the world, (Appe & Oreg, 2022; Chaudhry & Heiss, 2021)), wouldn’t we want to determine the most effective ways (and NGO’s) to benefits others and try to do as much good as possible with each dollar?

The PlayPump example

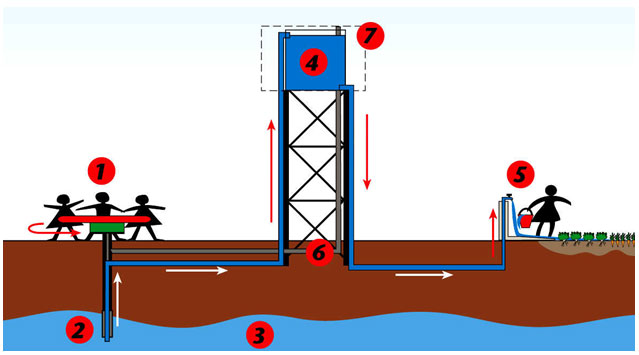

To exemplify the importance of choosing charities based on their effectiveness and not on their intentions or marketing, I will devote the following part to the PlayPump International project: In 2006, then- US President George W. Bush stated that a $60 million public-private partnership with PlayPump International has been agreed upon, a project that was meant to bring clean drinking water to up to 10 million people in Africa (Frontline World, 2010). The concept was simple: A merry-go-round is connected to a borehole. As children play, the spinning motion pumps water out of the ground and into a tank, making it available to the community at any time (PlayPump).

Photo by Envirogadgets, Columbia University

However, the promising new technology, combined with good intentions and financial support, did not live up to its promise of bringing clean drinking water to rural areas in Africa but instead resulted in a complete failure: In order to provide enough water for the community, the PlayPump would need to spin all day long, meaning that children and adults (mainly women) were not playing but walking endlessly in circles to get the water out of the ground. Unsurprisingly, within the first few years, thousands of pumps were abandoned or broke down and the old handpumps reappeared. The high costs of the pump ($14.000, excluding drilling), the complexity of the pumping mechanism and reliance on ‘child/women labour’, has been criticised by various reports of NGOs such as WaterAid and UNICEF (UNICEF, 2007). Eventually, in 2010, the NGO in charge, PlayPump International, had to shut down its operation and millions of dollars went down the drain (Stellar, 2010).

Effective Altruism

Apart from ineffective, poorly executed or even harmful aid projects that can be found around the world (Langat, 2019; GiveWell, 2007), isn’t it everyone’s responsibility and perhaps even moral obligation to ensure that less fortunate people are being helped around the world and that donated resources to humanitarian causes are being used effectively?

Already in 1972, Australian moral philosopher Peter Singer raised similar moral questions in his essay ‘Famine, Affluence, and Morality’ (1972), where he argued that, if one can use one’s wealth to reduce suffering, without any significant loss in the well-being of oneself or others, it would be immoral not to do so. Singer introduces the ‘drowning child’ scenario: Assuming I am on the way to work and walk past a shallow pond where a child is drowning, wouldn’t I save the child? Inaction is clearly immoral if a child is dying and someone can save it but chooses not to; just as the extra mile between the person in need and the person helping does not reduce the latter’s moral obligations (Singer, 1972, pp. 231-232). Since his thought experiment in 1972, EA has not only grown rapidly, but Singer also wrote several books, including ‘The Most Good You Can Do’ (2015), where he suggests that individual donors should prioritise effectiveness, coining the phrase effective altruism, which aims to motivate and inform giving by identifying need through reason and evidence in order to yield ‘the most effective ways to improve the world’ (Singer, 2015, pp. 4-5). In the mid-2000s, MacAskill and Toby Ord started to research the cost-effectiveness of charities fighting global poverty. And in 2009 they started the EA “meta-charity” Giving What We Can, which encourages people to donate at least 10 percent of their income to the charities with the greatest positive impact. At around the same time, Holden Karnofsky and Elie Hassenfeld, founded another organization, GiveWell, which focuses on in-depth research to identify the charities that do the most good (MacAskill, 2015, p. 110).

While EA clearly has a philosophical lineage, EA is not only a set of philosophical or moral ideas. Peter Singer approvingly cites a definition according to which effective altruism is:

“a philosophy and social movement which applies evidence and reason to working out the most effective ways to improve the world”. (Singer, 2015, pp. 4-5)

But does EA define as a social movement? While social movements have been perceived very differently over time and collective action and spontaneity are some of the main drivers for many social movements, I would claim that EA rather fits within the rational-choice-oriented resource mobilization theory (Tufte, 2017, p.85). Within that theory it has been argued that ‘the most effective social movements are those whose leaders and organizers are able to recognize the political, organizational, economic, and technological opportunity structures’ (Lievrouw, 2011, p.49). The dynamics and development of social movements is based on rational choices that are driven by navigating among opportunity structures. Rational analysis of costs and benefits drive the process forward (Tufte, 2017, p.85). In light of that, EA can be placed within that theoretical framework, seeing that at the heart of EA are the following three main characteristics:

• Impartiality (Individuals have equal and great moral worth)

• Cost-effectiveness (Some charities are far more effective than others, making them highly cost-effective)

• Cause prioritization (Resources should be distributed based on what will do the most good, irrespective of the identity of the beneficiary)

The rapid increase of efforts to enact the above-mentioned principles, including EA meta-charities, EA-influenced charities, EA blogs, TED Talks, podcasts, (e)books, conferences and so on, at a time when cross-border private aid flows were increasing, speak for a ‘resource mobilization movement’. Whereas in 1972/1973, Singer started out to spread his moral thinking through his academic writing and teaching, in the beginning of the 2000s, the new ‘leaders’ of EA started to ‘recognize the changing political, organizational, economic, and technological opportunity structures’, moving from ‘conventional’ forms of communication toward newer technologies. Adapting to the explosion of technology in recent decades (Harries, n.d., 2022), the EA organizers made use of this digitalization in form of EA podcasts, as the 80,000 hours podcast shows, Facebook groups, such as ‘Effective Altruism’ with its over 20.000 members, or TED talks, as the one given by Peter Singer, to name a few. And despite the fact these communication forms may not always be a ‘catalyst for social change’ (Denskus & Esser, 2015), the EA community successfully implemented them as an effective tool for information dissemination which in turn helped to popularize EA.

Misconceptions

Having considered what EA is and intends to do, let’s turn to certain misconceptions and criticisms of EA. Due to the limited scope of this blog post, I will focus on two particular criticisms only.

As I discussed and claimed above, EA can be placed within resource mobilization theory. Given EAs rational nature, are emotional characteristics that usually exist within social movements not being neglected? A lot of social movements are being defined and driven by emotions such as anger, anxiety, and outrage, but also by feelings of togetherness, optimism, and hope – all visible in many of the present uprisings. Assuming I participate in the Ice Bucket Challenge, or donate money to an organisation or charity that is less effective, solely on the ground to express my support, care, or love for, let’s say, a friend or family member, am I doing something that is less morally valuable? Both Singer and MacAskill describe within their books that through aspiring, effective altruists can move toward a more EA-consistent life, something that is being seen as positive – Participating in the Ice Bucket challenge or donating to ‘ineffective’ charities does not do the most good, still, the participation in these activities can also be seen as an individual’s process of moving toward doing the most good. Simultaneously, as long as donations are being seen as ‘luxury spending’ and do not replace donations (or activities) that do the most, there is no need to be against them (McAskill, 2014; McAskill, 2015; Singer, 2015).

Concurrently, effective altruists do recognize the role certain emotions can play (Singer, 2015, pp. 83-93, 171, and MacAskill, 2015, pp. 5, 11). Consider Singer’s anecdote of a student who announced that saving someone’s life, ‘would be the greatest moment’ in his life or the ‘effective altruists [that] prefer to focus on the good they are doing. Some of them are content to know they are doing something significant to make the world a better place’ (Singer, 2015, pp. viii and 133). Nevertheless, it is true that EA leaves not too much space for emotions such as anger or guilt. While Singer and MacAskill do not say that these emotions are bad per se, they highlight the value that the opposite holds (MacAskill, 2015, p. 32).

One of the most cited criticisms of EA is that it ignores political and systemic change (Rubenstein, 2016, pp. 517-519, Gabriel, 2017). Brian Leiter, for example, says: ‘I am a bit sceptical of undertakings like [effective altruism], for the simple reason that most human misery has systemic causes, which charity never addresses, but which political change can address; ergo, all money and effort should go towards systemic and political reform’ (Leiter, 2015).

However, effective altruism is actually open to systemic change, both as principle and as practice. Systematic change can be understood in a broader and a narrower sense. In the broader sense, a systemic change is any change that contains a sole investment to gain a long-term benefit. In the narrower sense, systemic change is a long-term political change. Be that as it may, the claim is often that effective altruists have been biased ‘by a desire for quantification away from difficult-to-assess measures such as political change’ (Todd, 2020).

It is clear that effective altruism is open to systemic change in principle: effective altruism is committed to cause-neutrality, implying that if improving the world in a systemic way will lead to do the most good, then it’s the best way of going forward in the effective altruists’ sense. More importantly though, effective altruists often advocate for systemic change in practice, even in the narrower sense. Examples of that include, but are not limited to: The advice that The Centre for Effective Altruism has provided for the World Bank, the WHO, the Department for International Development; numerous grants within the areas of land use reform, criminal justice reform, improving political decision-making, and macroeconomic policy that the Open Philanthropy has made; and promotion of alternative voting systems, in particular approval voting, which is run by a member of the effective altruism community (Todd, 2020).

Conclusion

If you have watched the TED talk ‘The why and how of effective altruism’, you probably were quite unsettled after having watched several people walking past the little girl as she laid there injured in the streets. You probably even thought that you would not have walked past. What then, as Peter Singer claims, if it would be possible for you to achieve a comparable result? Would you walk on by the people who need your help? By donating to effective organizations, you might have the opportunity to achieve a similar outcome as the one described above, even if the people are not in close proximity.

In this blog post I have tried to unpack the central idea of Effective Altruism. I have claimed that effective altruism can be organized within the rational-choice-oriented resource mobilization theory, instead of being associated with one of the ‘three generation social movement’ (‘ideologically driven social movements’, ‘new social movements’ and ‘transnational rights-based movements’) (Tufte, 2017, p. 84). While other criticisms of EA exist and is being addressed elsewhere (e.g., EA is just another form of utilitarianism or EA is ‘just’ about fighting poverty), I highlighted two common criticisms of effective altruism, namely that of being a cold-hearted rationalist movement and that of ignoring systemic change in its entirety. In doing so, I hope that I have contributed to future debates around the topic and encouraged the reader to further reflect upon the matter.

Word Count: 2281

Concluding remarks and reflections

The blog assignment has proven to be an informative and useful exercise that helped me to reflect on a variety of themes and issues that I otherwise would not have engaged with as much. Admittingly, I am not too involved in social media normally; share opinions and ideas online, read or write blogs and engage with other people on the internet. However, without really noticing, I found myself reading a lot of different blog posts from this year’s students, Tobias ‘Aidnography’ and even blogs created by students in the past. I followed links, articles and recommendations made in blog posts by other students and noticed that I enjoyed writing ‘shorter’ texts for our blog, reply to comments and comment on other people’s posts. Personally, I would have wished for more of an exchange or engagement of ideas and opinions between students and readers, but I suppose that that, given the limited timeframe and workload, would be a bit ambitious. After having discovered that replying to comments and commenting on other people’s posts requires a lot more time than I initially expected, the ‘limited’ exchange of ideas and comments is plausible.

The blog exercise depended a lot on teamwork, organisation and communication within the group, something that I experienced as extremely useful even though challenging at times. Seeing as the ComDev programme is a ‘distance’ course, I appreciate the effort to create an exercise where students from different parts of the world can come and work together and share their different experiences and insights. However, I would classify the blog exercise as demanding, which entails that other parts may have to suffer in turn (e.g., limited activity/comments on blog posts, taking on parts of the exercise one is familiarized with, instead of trying out something new).

All in all, I would say that blogging was a fun and interesting exercise, where different topics, and styles of writing could be experimented with, while simultaneously having the chance to get to know a few of our fellow students.

List of reference

Appe, S. & Oreg, A. (2021). Does effective altruism drive private cross-border aid? A qualitative study of American donors to grassroots INGOs, Third World Quarterly, 42:12, 2841-2862, DOI: 10.1080/01436597.2021.1969910. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Chaudhry, S., & Heiss, A. (2021). Dynamics of International Giving: How Heuristics Shape Individual Donor Preferences. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 50(3), 481–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020971045. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Denskus, T., Esser, D. (2015). TED Talks on International Development: Trans-Hegemonic Promise and Ritualistic Constraints. Communication Theory 25:2, 166-187. doi:10.1111/comt.12066. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

FRONTLINE/World (2010, June 29). Troubled Water. http://www.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/southernafrica904/video_index.html. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Gabriel, L. (2017). ‘Effective Altruism and Its Critics’. Journal Aplied Philosophy, vol. 34, pp.457-473. https://doi.org/10.1111/japp.12176. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

GiveWell (2007). Failure in international aid. GiveWell. https://www.givewell.org/international/technical/criteria/impact/failure-stories#Poorly_executed_programs. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Harries, D. (n.d.). Innovation: Can technology beat poverty? 2. Retrieved September 25, 2022, from https://stories.cgtneurope.tv/hubs/innovation-action-change/can-technology-end-poverty/index.html. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Langat, A. (2019, february 14). Nutrition supplements, but no one to distribute them. Devex. Do Good. Do It Well. https://www.devex.com/news/nutrition-supplements-but-no-one-to-distribute-them-93882. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Leiter, B. (2015). ‘Effective Altruist Philosophers’. Leiter reports. https://leiterreports.typepad.com/blog/2015/06/effective-altruist-philosophers.html. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Lievrouw, L. (2011). Alternative and Activist New Media. Cambridge; Malden: Polity

MacAskill, W. (2014, august 14). “The Cold, Hard Truth About the Ice Bucket Challenge,” Quartz, qz.com/249649/the-cold-hard-truth-about-the-ice-bucket-challenge/. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

MacAskill, W. (2015). Doing good better: how effective altruism can help you make a difference. Gotham Books.

Osili, U., X. Kou, V. Carrigan, J. Bergdoll, K. Horvath, C. Adelman, and C. Sellen, eds. (2020). Global Philanthropy Tracker 2020. Indianapolis, IN: Indiana University Lilly Family School of Philanthropy. https://scholarworks.iupui.edu/handle/1805/24144.Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Rubenstein, J. (2016). The Lessons of Effective Altruism. Ethics & International Affairs, 30(4), 511-526. doi:10.1017/S0892679416000484. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Singer, P. (1972). “Famine, Affluence, and Morality.” Philosophy & Public Affairs, vol. 1, no. 3, 1972, pp. 229–43. JSTOR, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2265052. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Singer, P. (2015). The most good you can do: How effective altruism is changing ideas about living ethically. Yale University Press.

Stellar, D. (2010, July 1). The PlayPump: What Went Wrong? Colombia Climate School – Climate, Earth, and Society. https://news.climate.columbia.edu/2010/07/01/the-playpump-what-went-wrong/. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Todd, B. (2020, august 7). Misconceptions about effective altruism. 80,000 hours. https://80000hours.org/2020/08/misconceptions-effective-altruism/?gclid=CjwKCAjwzY2bBhB6EiwAPpUpZv_5aTso0-Sh5mpt7sc3QH4xmF5GssR9H658zpUvZKEuiUCALd6V9BoC-9oQAvD_BwE. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

Tufte, T. (2017). Communication and Social Change: A Citizen Perspective. John Wiley & Sons.

UNICEF (2007, October). An Evaluation of the PlayPump Water System as an Appropriate Technology for Water, Sanitation and Hygiene Programmes. https://www-tc.pbs.org/frontlineworld/stories/southernafrica904/flash/pdf/unicef_pp_report.pdf. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

United Nations (2022, April 20). Swedish UNA: Budget cuts hurt the world’s poorest people. https://unric.org/en/swedish-una-budget-cuts-hurt-the-worlds-poorest-people/. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.

United Nations – Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights. OHCHR and protecting and expanding civic space. https://www.ohchr.org/en/civic-space. Accessed 7 Nov. 2022.