“What is morality police?” I wondered as I first read about the unprecedented death of Mahsa Amini back in September. Her life was lost at only 22 during a family visit to Tehran after her arrest by the morality police- Islamic religious police which detains violators of the Iranian dress code, usually women.

Mahsa Amini was pushed into a police van for “inappropriate attire”. That was her crime.

News of her fate sparked protests in the following days, rippling all over the nation and in cities around the world. The government has since called them “riots” and refused to be held accountable for any criminal actions while violence and brutality between the police and protesters have been surging.

The protests, mostly led by women, continue to this day though hundreds, perhaps thousands of people have been arrested. Over one hundred and eighty have been killed.

What Mahsa Amini’s death has exposed to the world is how deeply rooted the Iranian regime is in its violation of human rights. From systemically subjugating women, to justifying police brutality, and attempting to conceal atrocities by limiting contact with the outside world.

The attempt to silence

Shortly after the protests began, the Iranian regime imposed an Internet blackout in an attempt to demobilize the increasingly angry crowds. The country has some of the world’s most extreme censorship in the world and Iranians result to using VPNs in order to have access to social media and other sources of online connectivity. This communication “vortex” has so far proven unsuccessful in impacting the protest movement or cutting off the population from the outside world, something the Social Media ban in the country has meant, but failed to do for years.

In line with all of the network restrictions, censorship, and lack of journalist coverage, violence and arrests are also directed at protesters, activists, or journalists who attempt to get the story of what’s happening out into the world.

Many have been imprisoned already, and the majority of videos from the protests circulating the internet at this moment do not include close-ups of people’s faces or blur them altogether. Having your face in photos or videos from the demonstrations makes you a potential target for the government to threaten.

But just like the many ways ICT, or in this case, its forceful ban can be used to keep people silent and under control, it can be utilized against those who seek to oppress.

The voice of unity. “Women. Life. Freedom”

Two days ago, the Iranian state broadcaster’s evening news was hacked, showing an image of Iran’s supreme leader in flames, with a target on his head. Bellow him images of Mahsa Amini and three, even younger victims of his regime accompanied by a message to join the protests.

This hacker’s message provides a rather colourful and imaginative counter-narrative to the television propaganda the Iranian government has been spreading of late, claiming Iran’s enemies are to blame for the protests.

In line with this “retaliation”, there has been content circulating across social media, exposing some of the crimes the regime is attempting to hide.

This tweet and many like it have videos attached to them, showing police brutality on civilians, guns being fired at them, and, in some cases, even showing the killings of people.

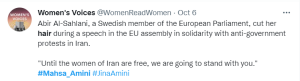

Video testimonies have also been a source of solidarity for the women of Iran from outside the country. Videos of women and men, some of them activists, politicians, academics, or celebrities, all cutting their hair in support of justice and freedom for Iranian women, who have also been cutting their hair in public and burning their scarves.

The protests have united many people of all ages and backgrounds in Iran and beyond behind one goal- change. What started with a protest in one city, spread across the nation and beyond, caused sanctions against Iran by a few countries, and is now joined by a worker’s strike in the energy sector. Only time will tell if this will turn out to be yet another freedom movement to be extinguished by a criminal regime like history shows.

Through their attempt to keep women silenced, Iran’s Islamic regime brought on itself the threat of a new revolution. People’s voices, those of women and men alike, demand their needs and freedoms as a society. The freedom to choose what to wear, the freedom from uncalled-for police violence, and the freedom to voice their stories.

Although Iranians are clearly not swayed by their government’s ban on communication information sharing, such measures create restrictions beyond my ability to even comprehend. Whilst following the events of the past few weeks, I have noticed how scarce the information sources are. Most news broadcasters rely solely on the videos ordinary citizens share online to show what is happening. Images we would normally have access to through journalism.

“The success of the executions in the summer of 1988 was the secrecy of it” said a witness at the Iran Tribunal in Hague in 2012.

This time women and girls lead. This time the silence is broken by Social Media. Will this time be different?

It is beyond the scope of this post to address this topic fully and my attempt was a more general (and short) overview of some of the ways ICT is being used for or against the poeple of Iran on their quest for women, life and freedom.

I would love to hear your thoughts on this topic so let me know in the comments!