My last blog post discussed the lack of attention that the Yemeni conflict is getting by the public at large and western media in particular. It also highlighted the extreme poverty within the country, the decreasing funding by the international community and the devastating consequences that leads to.

Today’s post, on the other hand, will focus on the communication of development and poverty generally and how that communication might affect the narrative around it and the ability to end it.

Poverty can be described as having:

‘many faces, changing from place to place across time, and has been described in many ways. Most often, poverty is a situation people want to escape. So poverty is a call to action — for the poor and wealthy alike — a call to change the world so that many more may have enough to eat, adequate shelter, access to education and health, protection from violence, and a voice in what happens in their communities.’

To end extreme poverty, effective communication is pivotal. Far too often misconceptions are being spread that impact opinions about poverty and influence the actions of decision-makers and leaders who have the power and resources to end it.

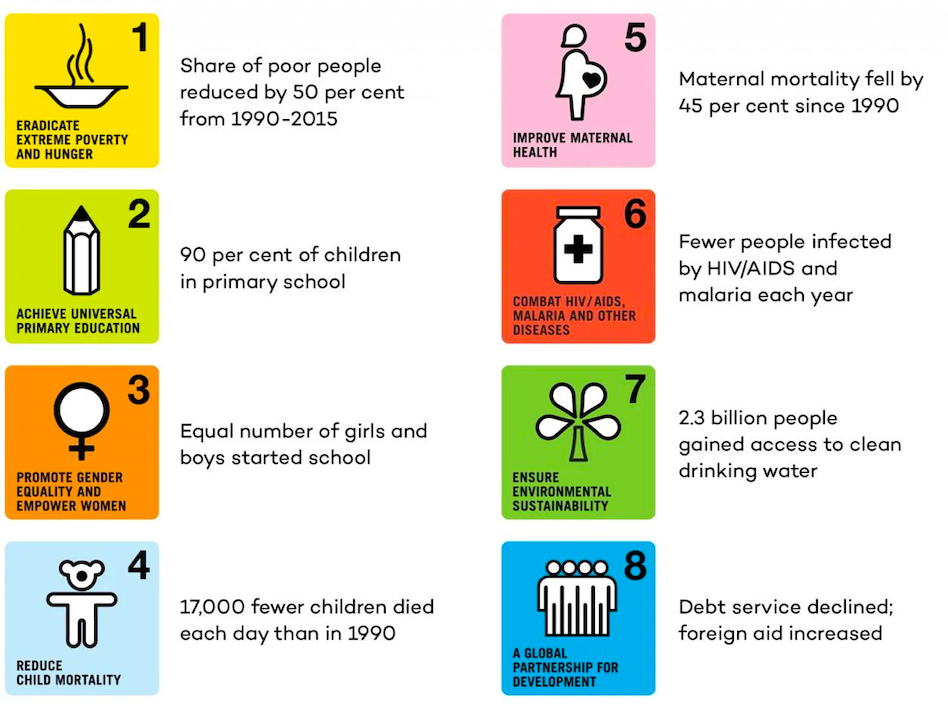

In September 2000, the leaders of all 193 countries signed the Millennium Declaration, in which they decided to achieve a set of eight measurable goals, ranging from ending extreme poverty to promoting gender equality, by a target date of 2015.

Photo by MGDMONITOR

Even though the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) did not consider the multidimensional nature of poverty (factors that contribute to global poverty, environmental causes of poverty etc.), by the end of 2015 there was a significant progress: decline in extreme poverty and reduction of global under-five mortality rate and HIV infections, to name a few.

Photo by the International Institute for Sustainable Development

The United Nations Millennium Development Goals encouraged all nations to help achieve the set of goals, but also determined that all countries should allocate 0.7% of their gross national income to overseas development assistance. While 0.7% was initially regarded as a minimum commitment to the poor, only a few donors have consistently allocated 0.7% or more of national income to aid (Luxemburg, Norway, Sweden, Germany, and Denmark among them).

In 2020, then-President Donald Trump proposed a 21% cut in foreign aid on the grounds that other countries are not paying their fair share. It is indeed true that the US is spending more on foreign aid than any other country in the world, but only in absolute terms. America spends less than 1% of its budget (around 0,18%) on foreign aid, which lays well below the target percentage of 0,7%. Other countries such as Germany, despite having an economy less than a quarter the size of the US, was ‘only’ a little less than $10 billion behind. If further foreign aid cuts are implemented in the US, while Germany maintains its aid spending, the US would no longer be the biggest donor, even in absolute terms.

Photo by the United Nations

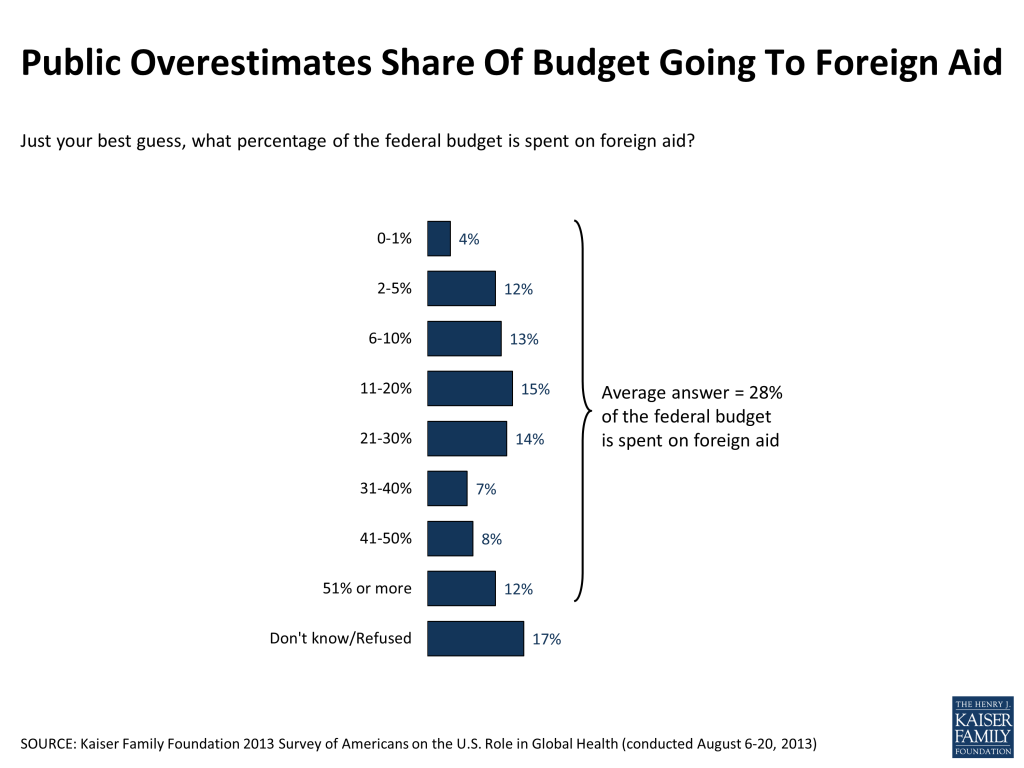

Unfortunately, many Americans seem to believe Trump. When asked, Americans constantly overestimate how much of their federal budget goes to foreign aid. The Kaiser Family Foundation that tracks public opinion on global health since 2009, found that the average public believes that 25% of the entire federal budget is being spend on foreign aid. When asked how much would be appropriate to spend, people tend to say 10%. Now imagine the US would really spend 10 % of its federal budget on foreign aid…

Photo by Kaiser Family Foundation

The misconception that the world is spending way more money on foreign aid than it does, combined with the believe that the world remains poor, and efforts to combat poverty is a waste, is a damaging narrative that can lead to a negative view on foreign aid, and the cutting of humanitarian and development funding. The UK government, for instance, just cut its aid budget in 2020 by 51%. Aid to Ethiopia, for example, was cut by 55% (from £241 million in 2020/21 to £108 million in 2021/22) and aid to Yemen was cut by 63% (from £221 million in 2020/21 to £82 million in 2021/22). While the cutting of funding by the UK does not necessarily imply that the UK sees foreign aid as a complete waste, they did cut their funding at a time where the COVID-19 pandemic increased the global extreme poverty rate to 9.3 %, indicating that more than 70 million people were forced into extreme poverty.

Pessimism and the believe that the world is a hopeless place is understandable if one reads and watches the depressing news every day. Constant negative reporting on famines that struck a country, floods that are washing away entire cities and dictators taking over yet another country, lead to the belief that the world is getting worse by the second and that solving extreme poverty is an impossible task. However, the opposite is the case: The world is better off now than at any point in human history. More than 1.2 billion people have risen out of extreme poverty since 1990. Global life expectancy has more than doubled in the past century and many nations that received aid in the past are now self-sufficient. Countries are getting richer; child mortality has fallen by more than half since 1990 and illiterate rates fell from 88% of the world’s population to 10%. Of course, there are still around 689 million people living in extreme poverty, so it’s not time to celebrate YET. But isn’t it striking that regardless of all the progress that we are making we are cutting, instead or increasing, foreign aid?

Wouldn’t it be worth it to highlight the striking progress the world is making and the huge impact that humanitarian and development aid is having? Perhaps it would encourage people to keep giving and decision-makers to support foreign aid?

Share your thought in the comments below and let us know what you think about the topic?