In my first blog post, I hinted at the potential ICT has to invite for more individual and community-based participation and the possibility for empowerment. In my second post, I suggested that participatory action can accumulate and multiply through ICT, turning into a movement for social change. Through my last post, I am reflecting on racial inequalities in representation in the US, for black girls in particular, through three different information sources from which young people gain knowledge of society. I aim to show how some seemingly subtle changes can initiate social decolonization.

In September this year, Disney released the first trailer of the live-action film ‘The Little Mermaid’ on their YouTube channel, gaining over a million dislikes soon after (Yates). The problem appeared to be the fact that the actress playing Ariel was Halle Bailey, an African-American singer, songwriter and actress. The reactions it sparked on social media formed two opposing conversations. On one hand were those saying Ariel should be white as she is originally in the animated film, while others were baffled that a heroine based on a Danish fairy-tale can be black.

On the other side stood those who accepted it, some who celebrated it, and even some who called out what they viewed as a white entitlement or even racism.

Since the film is only based on the original fairy tale, has a different storyline, and is fictional, what caused such a quick, negative reaction? After all, there are countless examples of white actors playing the role of a person of colour, with little criticism as a reaction. A simplified answer to this representation gap is the legacy of a white-supremacist colonial ideology, according to which whiteness is what is ‘normal’- a normal of which an African-American mermaid is in violation.

Disney was founded in 1923 and, much like other entertainment or any other type of business across the US, for decades it was aimed predominantly at white audiences. In many ways, what the US society consumes is still produced mostly for white people by white people (Marketing charts). The lack of representation of black people, which isn’t loaded with negative stereotypes, is only one part of the normalized racial discrimination in the country.

- The colonial bricks at the foundation of societal beliefs

During colonial times, ideas and knowledge from the West were put above those of cultures outside modernity, rendering them as ‘backward’ (McEwan 159), forming the unequal power relations between them, which are still prominent today. Since the US is not only the world’s largest economy but also one of the lead distributors of popular culture (along with other socio-political and economic factors) worldwide, it is a powerful influencer in shaping beliefs and ideologies across cultures (Oussayfi). Since popular culture is a product of (and for) people’s interests and as such reproduces familiar worldviews, it succeeds in strengthening and redefining certain beliefs and ideas as ‘popular’ or normal. If the image of America is still white, Christian, masculine, etc, and the representation of different groups is not on equal terms, that binary opposition of ‘self’ and ‘other’ is still justifying centuries-old colonial dominance (McEwan 151). When mixing the history of slavery and racism into the matter and combining that with misogyny and the often-white face of feminism, one can identify black girls and women as one of the most marginalized groups in the US (Hooks 53).

Young black girls today can see themselves in Holly Bailey as a mermaid princess, as well as all over the media, after years of criticism against the lack of black representation on screen and even so, the choice of the actress was met with outstanding resistance. In the top forty list of the most popular films globally there is an overwhelmingly white cast, especially in films made prior to the last decade (Dinosaw). In addition, black representation on the small screen has not always been diverse. Although many US shows in the ’90s featured mainly black actors and actresses, they were marketed at black people and were later phased out in favour of the likes of ‘Friends’ and ‘Everybody Loves Raymond’, according to the taste of white audiences (Leftwich). If we look at US television today, black actors make up 12% of leads in broadcast shows (McKinsey) but a lot less as directors or writers. The building blocks of racially-homogenous culture in US society, however, go far beyond representation in popular culture and reach to the core of the very fabric of society.

- Education and racial inequality in the US

As McEwan points out, ‘knowledge is never innocent but is profoundly connected with the operations of power’ (76). Knowledge production can occur on many levels, one of which is through traditional means of education such as schools and universities. In July this year, Harvard graduate Julieanna L. Richardson held a TED Talk called ‘The Mission to Safeguard Black History in the US’ in which she tells her life story and how she came to establish the US’s largest African-American video-oral history archive (2022). ‘The History Makers’ is a non-profit research and educational institution working to preserve and spread stories of African Americans, and in doing so, reshape inclusivity in American history (The History Makers). Richardson founded ‘The History Makers’ after she spend her childhood, adolescence and university years learning all-white American history and taking these teachings as fact, only to discover later that history is white because it was white people who made it into history books, while other history-makers were left out.

“Today, from our board rooms to our classrooms, on TV and social media, debates are raging about whose history matters. Those who document their history are who society says matters. For the black community, that documentation has been elusive” (Richardson 3:30-3:57).

Institutional structural racism is and has always been one of the catalysts for racial inequality in the US. With regard to education, the Human Right’s Watch report point to great racial disparities among students (2021). Higher suspension and expulsion rates for black and minority children, discriminatory discipline and criminalization, and unequal facilities are only some of the ways these inequalities are manifested. These discriminatory circumstances enforce negative patterns in black and other minority communities. Looking at other institutional racial inequalities stated in the same report such as mass incarceration of black people points to the educational setting as a base from which young African-Americans begin a cycle of poverty and crime. As far as the content of US education, the Human Rights Watch states:

Learning Black history is beneficial to all students: While enhancing the self-esteem of Black students, it conveys historical realities to all students and encourages empathy, understanding, and efforts to avoid repeating the racist violence of the past. Further, denying the historical and contemporary realities of racial discrimination impedes not only justice and accountability for historic wrongs, but the eradication of persisting structures of racial inequality … (2022).

Popular culture in the US has so far been overwhelmingly white, with little sensitivity when it comes to representation, reflecting the country’s persistent colonial mindset. Structural racial inequalities in turn have succeeded in maintaining the white-supremacy status quo. If young people, for whom information through pop culture and education shapes beliefs and attitudes towards themselves and others, are shown a one-dimensional, colonialist idea of society, the cycle of inequality remains. So, are there alternative, non-institutional practices which can bring about the decolonization of the US society?

- Decolonization in the digital world

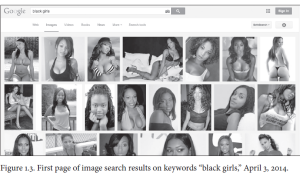

As already mentioned, black girls and women in the US are disproportionately affected by racial discrimination. Along with suffering some of the negative stereotypes and misrepresentations that black men are subjected to, black female bodies have been overly sexualized since early-colonial times (Hooks 24). In her book ‘Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism’, Safiya Noble critically examines her finding from researching racial-biased search algorithms: ‘I could see the connection between search results and tropes of African Americans that are as old and endemic to the United States as the history of the country itself’ (18). When she Google searched ‘black girls’ in 2014 the majority of first-page results were cantered around pornographic content:

After my own search for ‘Black girls’ on Google in October 2022, I compared the results to the same search Noble conducted in April 2014 and found a different type of content:

The first two pages showed ten results related to the discrimination against black girls in schools (marked in red), and twelve results related to more general negative experiences of black girls and women in the US (marked in blue). Over half of the top ‘black girls’ image search results point to the still living and breathing racial and gender bias black girls and women face, and its negative consequences. This time around, the initial results not only do not demonstrate negative or sexualized representation but instead point out some of the most significant forms of subjugation for black girls in the US.

The search engine which only a few years earlier was reproducing and reinforcing an objectifying and racist image of black women has been at least partly optimized. Technology is indeed a mirror of injustice and societal bias, as Birhane suggests (2019), and the production of the ethical framework of AI is extremely difficult and controversial. Amongst the many challenges of data-driven systems is the fact that algorithms are not neutral but are based on opinions, often informing stereotypes, and harming society’s most disadvantaged. As Noble claims: ‘Technologies and their design do not dictate racial ideologies; rather, they reflect the current climate. As users engage with technologies such as search engines, they dynamically co-construct content and the technology itself.’ (151). The change in search results for ‘black girls’ between 2014 and now is clearly a reflection of a shift in user behaviour online, along with Google’s action for more ethical AI (Birhane). As social media and other communication and information platforms have allowed for anyone’s voice to be heard and amplified, an ocean of information and knowledge has emerged and begun to redefine online data.

If search results for ‘black girls’ point a finger at racial inequality and digital records of African-American history are a mouse click away, then challenging racial discrimination and misrepresentation is shifting from mere conversation to action. Popular culture, education, and online information are sources from which young people in the US learn about the structure of society. Who is represented and how, whose opinion matters, and whose history matters are all programming the minds of youth.

The digital space has created opportunities to tackle racial inequality where institutions have failed. Google search algorithms are shifting, black history is being made available online and everyone across the world with access to the internet can see one of the most iconic Western animated fairy-tale characters as black.

Decolonizing society occurs on a few levels. Partly through criticizing the knowledge produced and distributed by the Western experience, which ignores and undermines the knowledge and experience of ‘others’ (McEwan 90). Additionally, criticism of Western knowledge production is not enough, but a move ‘towards the removal of enduring forms of colonial domination’ (91). Decolonizing the mind is important for those who were subjugated by colonial ideologies and also those who benefit from them. It is as important for the dominant as it is for the dominated group to release and rewrite old belief systems, in order to change the existing norm. Attempts to decolonize structures in so-called developing countries and former colonies from a racially-biased, White-supremacist norm would fall empty without eliminating the same patterns in developed countries. Decolonizing the US society could pave the way for US decolonization elsewhere. Changing how black people are viewed in the US could change how they are treated everywhere else in the world, by white people, by other groups and, most importantly, by themselves.

Reflections:

Taking part in the creation and development of this blog has been a unique experience. Keeping to a posting schedule has been a good stimulus for organizing the time needed to research and write the articles for the posts. Being able to adapt to a more casual tone of writing has made the experience easier since it has given me more room to be creative, as well as not worrying about and spending too much time on referencing. Learning more about the use of WordPress has been an asset, which I believe will aid me in future employment. Perhaps the most entertaining, although time-consuming part has been searching for different images as a header for the posts and matching them to the topic’s message.

I did however find it hard to place myself within a theme at the very start of the semester, without having much time to consider which topics I might be interested in writing about. The experience is even more limiting when trying to find common ground on topics as a part of a large group of people with very different subjects of interest. As a learning experience, it succeeds and has a lot of potentials to inspire, although it is not fully practical due to some agency factors: if a student is to create a blog in real life, they would have full control over their content, design, topics, etc. Finally, it has been very difficult to juggle between work, studies and the blog, with additional stress added by the fact that everyone can criticise my content, not only the academic staff. After this experience, I feel like blogging is not something I would like to engage in again as it has brought on a lot of anxiety but I have nonetheless gained a lot from the process.

Works cited

Birhane, Abeba. “The Algorithmic Colonization of Africa’. Real Life, 18 July 2019, https://reallifemag.com/the-algorithmic-colonization-of-africa/.

Dinosaw. “Most Watched Movies Of All Time”, IMDb, 16 Jul 2013, www.imdb.com/list/ls053826112/.

Dunn et al. ‘Black representation in film and TV: The challenges and impact of increasing diversity’, McKinsey & Company, 11 March 2021, https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/diversity-and-inclusion/black-representation-in-film-and-tv-the-challenges-and-impact-of-increasing-diversity.

Mandipie4u. ‘Black Little Mermaid Memes’, Guide4moms, 2022, https://www.guide4moms.com/2022/09/black-little-mermaid-memes.html.

Hooks, Bell. “Black Looks, Race and Representation”, South End Press Boston, 1992.

Human Rights Watch. ‘Racial Discrimination in the United States’, Human Rights Watch, 8 Aug 2022, https://www.hrw.org/report/2022/08/08/racial-discrimination-united-states/human-rights-watch/aclu-joint-submission#_ftn258

Leftwich, Ruby. ‘In (A Lot Less) Living Color: What Happened to All the Black TV Shows?’, The Ohio State University, Dec 2020, https://odi.osu.edu/lot-less-living-color-what-happened-all-black-tv-shows.

Marketing charts. ‘US Marketing and Advertising Industry Still Lacks Racial and Ethnic Diversity’, 5 Dec 2019, marketing charts, https://www.marketingcharts.com/business-of-marketing/staffing-111207

McEwan, Cheryl. “Postcolonialism, Decoloniality & Development”, Taylor & Francis Group, 2018. ProQuest Ebook Central, http://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/malmo/detail.action?docID=5606235.

Nattramn, Emi. ‘Officially, the Little Mermaid trailer has surpassed one million dislikes…’, Twitter, 12 Sep 2022, https://twitter.com/eminattramn/status/1569154367831539712.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. ‘Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism’, New York University Press, 2018.

Oussayfi, Taieb. “The global reach of US popular culture”, Medium, 23 July, 2018, https://medium.com/@taieboussayfi/the-global-reach-of-us-popular-culture-d31be4aaeb4b.

Richardson, Julieanna. “The Mission to Safeguard Black History in the US”, TED, YouTube, 20 July 2022, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I-sKZBcLKP4&t=687s.

Sims, Chelsea. ‘Ariel wasn’t Black!…’, Twitter, 10 Sep 2022, https://twitter.com/UmEarth2Chelsea/status/1568718526919098374.

The HistoryMakers. 2022, www.thehistorymakers.org.

Yates, Shanique. “Fans Call Reactions To ‘The Little Mermaid’ Trailer Racist As Film Generates 1.5 Million Dislikes On YouTube In Two Days”, AFROTECH, 16 Sep 2022, www.afrotech.com/youtube-removes-dislike-button-from-the-little-mermaid-trailer.