We live in an increasingly connected world, where the pervasive use of technology is impacting all areas of living. Internet connectivity and widespread use of digital devices are allowing the emergence of new opportunities that come from digitization and technological mediation.

Information and communication technologies (ICTs) play a preponderant role in the globalization process and are receiving greater attention as a means of addressing pressing challenges such as poverty or inequality, and stimulating economic and social development.

“New technologies hold the promise of the future, from climate action and better health to more democratic and inclusive societies. … Let us use them wisely, for the benefit of all.”

António Guterres, UN Secretary-General, 20211

According to Toyama2, ICT4D3 emerged from the intersection of the rise of an international development community craving for innovative solutions to very difficult socioeconomic challenges, and the expansion of a thriving technology industry into emerging markets and philanthropy.

Following this trend, large investments were made in projects that intended to increase digital connectivity or to provide technological solutions for development issues, such as education or health. These initiatives tend to present technology – particularly the most recent, such as computers, mobile phones, and the internet – as a tool for achieving key social and developmental goals.

But ICT4D interventions are far from being consensual and many critical voices have arisen in this context. Although digital isolation of developing countries is rapidly decreasing, the inequalities have worsened in recent years and the ICTs contribution to poverty reduction remains blurred.

The ICTs-magic-bullet lost some of its appeal before images of unused or broken technologies in rural settings and falling short of expectations. There are multiple examples of technological failures in the face of the lack of training and maintenance, inadequate infrastructure, lack of adherence to socio-cultural norms and community participation, poor public policies, or the mismatch of technologies to real local needs4.

Bringing a different perspective to the discussion, Toyama5 suggests considering technology as a magnifier with a multiplicative impact on social change. This means that technology has positive effects if people are willing and capable of using it positively, if it is applied to contexts where human intent and capacity already exist, or along with heavy investments in the development of human capabilities and institutions.

The author argues that techno-utopians equate technology penetration with progress, in what he calls the “myth of scale”, preferring to spread technology instead of pursuing extensive change in social attitudes and human capacity.

“In other words, it is much less painful to purchase a hundred thousand PCs than to provide a real education for a hundred thousand children; it is easier to run a text-messaging health hotline than to convince people to boil water before ingesting it; it is easier to write an app that helps people find out where they can buy medicine than it is to persuade them that medicine is good for their health. It seems obvious that the promise of scale is a red herring, but ICT4D proponents rely—consciously or otherwise—on it in order to promote their solutions.”

Kentaro Toyama (2012)[5]

Are ICTs shrinking the digital divide and empowering the most vulnerable?

Globally, societies are embracing technology and its myriad of tools, which is dramatically changing the way we communicate and interact6. But is the access to digital networks truly shrinking the digital divide and empowering the most vulnerable groups or is it reproducing existing power relations and patterns of (dis)advantage?

The Digital Divide adds to the existing forms of discrimination, deepening the social gaps related to education and income, as it limits access to resources and widens inequalities based on gender, disability, age, or socioeconomic status7.

Photo by buian_photos on Unsplash

Although the discussion about women’s empowerment and ICTs has been going on for several decades, recent evidence shows that there is still a long way to go when it comes to the inclusion of women in the information society. Various ICT4D interventions were aimed at this digital gender divide, revealing positive signs while failing to fully address inequality while exploring pre-existing structures and perpetuating power imbalances.

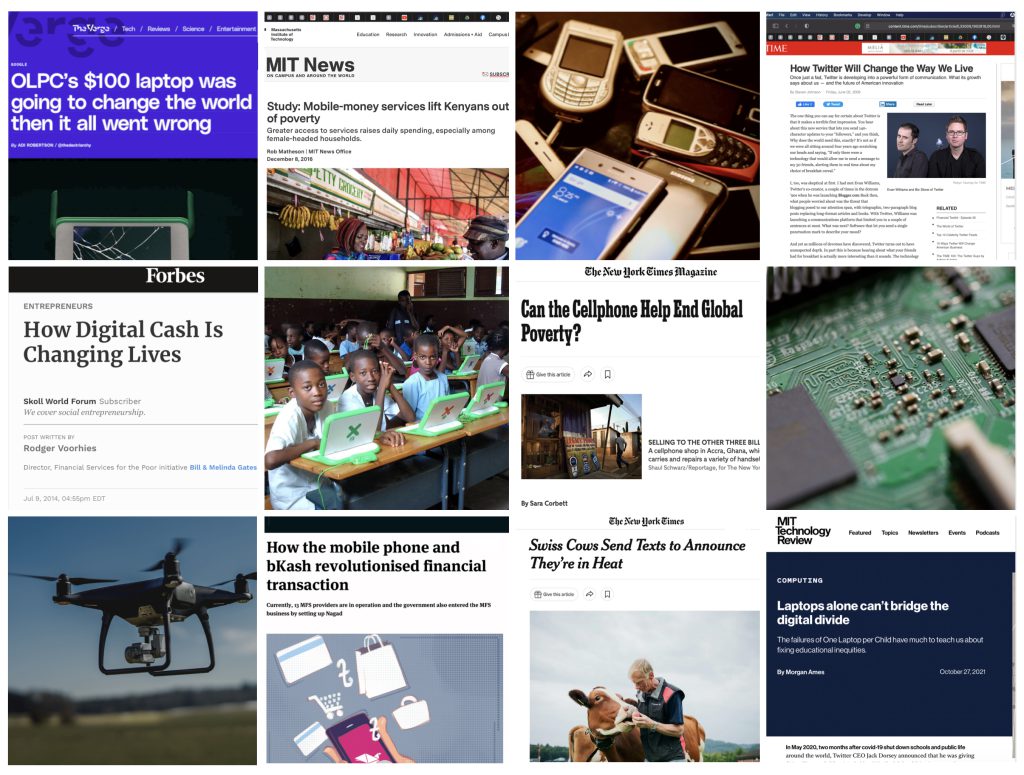

In addition to female empowerment, other areas such as education, health, or agriculture have been popular among ICT4D interventionists. Throughout the years, numerous projects came out, selling the idea of ICTs as the next silver bullet to solve education problems in disadvantaged settings. Simplistic and miraculous headlines sold technology as a pathway from global imbalances. The ambitious One Laptop Per Child project, led by the MIT Media Lab founder Nicholas Negroponte, is a good example of this historically recurring idea of technology as a cure to the ills of society.

“[D]evelopment often fails even on its own terms. Perhaps because ICT4D is centered on technology as a central agent of change, it tends to focus on the effects of technology at the individual or organization level, rather than on structural characteristics and changes”

Mark Graham (2019)8

The global influence of ICTs is undeniable, and technology has a huge potential impact that can be put to work towards the reduction of inequalities and fostering development. After several decades of ICT4D implementations and reflections, it is important to learn from past mistakes in order to improve development practices and not to be dazzled every time a new gadget comes out.

We will continue this discussion in future articles, looking at the impact of ICT4D projects in different areas. Meanwhile, feel free to share your thoughts with us in the comments or engage in conversations on our social networks.

Notes:

[1] UNCTAD, Technology for all. Technology and Innovation Report, 2021.

[2] Toyama, K. (2012). Can Technology End Poverty?

[3] a banner used to refer to the use of ICTs in development settings

[4] Steinberg, J. (2003). Information Technology and Development: Beyond Either/Or. Brookings.; Toyama, K. (2011). Technology as amplifier in international development. Proceedings of the 2011 iConference, 75–82.

[5] Toyama, K. (2012). Can Technology End Poverty?

[6] Hilbert, M. (2011). Digital gender divide or technologically empowered women in developing countries? A typical case of lies, damned lies, and statistics. Women’s Studies International Forum, 34(6), 479-489.

[7] Mackey, A., Petrucka, P. (2021). Technology as the key to women’s empowerment: a scoping review. BMC Women’s Health 21, 78

[8] Graham, M. (Ed.). (2019). Digital economies at global margins. The MIT Press.