Dear readers,

an investigation from the British Broadcasting Corporation – the BBC – has found that Syrian families have been livestreaming on the popular social media platform TikTok, which has a user count of more than 1 billion in 154 countries (Ruby, 2022), for several hours daily.

These families, however, are not livestreaming typical humorous TikTok content, but are engaging in internet begging by asking TikTok users globally to donate virtual gifts to them, which can later be cashed out. A “virtual lion” is worth 500 US dollars, according to one of the families.

Internet begging and child involvement

What is internet begging? According to the definition on Wikipedia (2022), the term refers to “cyber-begging, e-begging or Internet panhandling [and] is the online version of traditional begging, asking strangers for money to meet basic needs such as food and shelter.”

Taylor (2017:2), quoting Greenfield (2013): “provide the ability to track and monitor citizens in every aspect of their lives”, which is especially true in Low- and Middle-Income Countries (LMICs).

“the greatest burden of dataveillance (surveillance using digital methods) has always been borne by the poor.”

“Robert Kirkpatrick of the UN’s Global Pulse data science initiative has said of developing-country citizens that ‘privacy is your right. So is access to food, water, humanitarian response.” (p. 9) I would argue that specially children who had already been subjected to having to leave their safe surroundings and move into a refugee camp due to the ongoing conflict, are in dire need of a psychological safety net provided by their parents.

While there are no peer-reviewed public studies yet on the October 2022 phenomenon of internet begging on TikTok, there are authors who have dedicated their research to the subject of begging and exploitation in third-world countries. According to Fuseini and Daniel (2020:3), child begging is the “worst form of child labour” and “includes child exploitation, child delinquency, idleness, and deceitful manipulation of public to stir up their sympathy.” While other authors such as Stones (2013) and Swanson (2010) believe that begging may be educational and contribute to psychological advancement, within the clergy, “Islam strongly condemns begging in general, more especially when it involves children.” (Fuseini and Daniel, 2020:5).

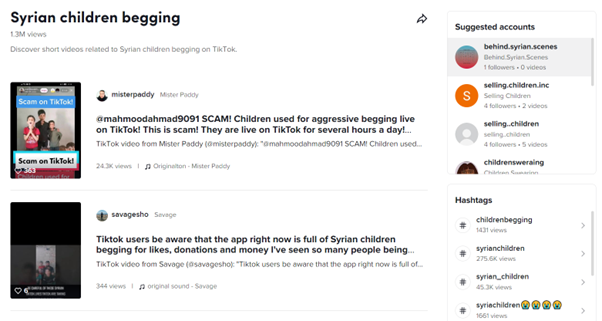

The below is a screenshot of the TikTok search results that appear when typing in “Syrian children begging”. With 1.3 million views on TikTok overall and the hashtag #syrianchildren counting more than a quarter of a million views since the “trend” was uncovered by a BBC investigation in October 2022, this is a worrisome development.

A TikTok account named “hannahjournalist” provides a comprehensive overview of the issue. Hannah Gelbart, Mamdouh Akbiek, and Ziad Al-Qattan teamed up with the BBC Global Disinformation Unit, BBC News Arabic, and BBC Eye Investigations to produce this 03:19-minute video:

While the struggles of the Syrian families in refugee camps are undoubtedly real, Neuman (2017) asks the important question whether aid agencies produce humanitarian imagery – both moving and still – for themselves. He states that these, alongside hashtags and opinion campaigns, accompany “traditional images of victims of epidemics or countries at war” (p. 15). While the author claims that the public’s attitude towards humanitarianism and development has not changed in the sense of having more compassion with the victims, the result of the use of these images or videos is a higher level of “self-intoxication of the milieu”.

In this case, the degrading notion of the Syrian families – already displaced due to a country at war – now begging for help to the people of TikTok. At the same time, it circumvents or even eliminates the “middlemen” (the development workers who are on the ground), and puts the “hero figure” (Neuman, 2017:5) onto the individual donating as he/she is able to witness first-hand the gratitude of the families begging rather than being unsure if their donation will reach these families while giving to humanitarian/development agencies.

Simultaneously, while circumventing the aid organisations or humanitarian/development agencies, the impact of the aid workers on the ground may be severely impacted. Hor (2017) argues that “aid workers regularly experience emotional anxieties that question their impact as an aid worker and their complicity in the suffering of others” (p. 1). At the core of their practice, according to the author, lies the avoidance of “the names and faces of victims whose gaze demands a response” (p. 6) while on TikTok, the families through very personal livestreaming and allowing a glimpse into their refugee camps, the individuals watching now get a first-hand glimpse into their gaze and a face to their names – often hours on end. I would argue that if skilled aid workers are already dealing with anxiety based on the victim’s suffering, what kind of damage could the circumvention of these middlemen have and what would the psychological impact of the viewers be without perhaps ever having been exposed to this type of suffering? Especially since the minimum age of TikTok users is 13 years old who have unparalleled access to viewing this type of victim exploitation and who might have never seen anything alike.

Thank you very much for reading to the end and I look forward to lively discussions directly on the post’s “Comments” section as well as on Facebook and Twitter. What did you learn about TikTok’s effect on families who use the platform to livestream, not to document their lives but to actively engage in begging? Do you think there should be any restrictions imposed to this kind of interaction with the audience? And what is something you feel was missing in the analysis? I’m eager to know and to broaden my horizons. Thank you in advance for the engagement!

“Read” you next time!

References

Denskus, T. and Esser, D. E. (2013) Social Media and Global Development Rituals: a content analysis of blogs and tweets on the 2010 mdg Summit, Third World Quarterly, 34:3, 405-422.

Dewiyanti, D. and Rosmalia, D. (2018) IOP Conf. Ser.: Mater. Sci. Eng. 407, 012073.

Fuseini, T. and Daniel, M. (2020) Child begging, as a manifestation of child labour in Dagbon of Northern Ghana, the perspectives of mallams and parents, Children and Youth Services Review, 111, 104836.

Hor, A. (2017) Searching for Redemption: Distancing Narratives in the Everyday Emotional Lives of Aid Workers, Working Draft, March 24, 2017.

Neuman, M. (2017) Dying for humanitarian ideas: Using images and statistics to manufacture humanitarian martyrdom, online.

Accessible at: https://msf-crash.org/en/publications/humanitarian-actors-and-practices/dying-humanitarian-ideas-using-images-and-statistics

Accessed on October 23, 2022

Ruby, D. (2022) TikTok User Statistics (2022): How many TikTok Users Are There?, online.

Accessible at: https://www.demandsage.com/tiktok-user-statistics/#:~:text=One%20billion%20active%20users%20spread,media%20platforms%20as%20of%202022

Accessed on October 24, 2022

Taylor, L. (2017) What is data justice? The case for connecting digital rights and freedoms on the global level, Working Draft, February 16, 2017.

TikTok (2022) Underage appeals on TikTok, online.

Accessible at: https://www.tiktok.com/safety/en/guardians-guide/

Accessed on October 23, 2022

Wikipedia (2022) Internet begging, online.

Accessible at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Internet_begging

Accessed on October 23, 2022