Image: Katarzyna Pierzchała via Facebook

Revolution has started in the rain

Dear readers,

in the early autumn 2016 on the 3rd of October, rivers of black umbrellas moved through streets of Polish cities and towns. It was a rainy day so an umbrella served a practical role, and soon after became a symbol of a new social movement that grew from a rising frustration and anger about government’s plans to implement an almost total abortion ban. , “a revolutionary moment when fear and anger were transformed into feelings of solidarity and empowerment, a moment of personal and collective transformation” (Korolczuk, 2016, p.92). For many people it was the first time attending a protest, for many it was a moment of an activist awakening, but for all it was a fight that we simply needed to win, a fight for the right to choose your life and a fight for the right to live.

Abortion as a hot topic

Abortion issue in contemporary Poland is a highly politicised and sensitive topic that sparks a lot of emotions on both sides on the fence. Thanks to the government that is tightly linked with the Catholic Church, the country is now seen as a stronghold of conservative values, with LGBTQA+ people and women receiving the biggest backlash. Especially controlling access to reproductive rights like safe abortion, contraception or in-vitro seems to be the current government’s favourite passtime. But it wasn’t always like that. Abortion was practically legal on request up until 1993 when the law has changed to allow abortion only in cases of rape and incest, if the mother’s life was at risk, and in cases of serious malformity of a fetus (Nowicka, n/d, p.170; Korolczuk, 2016, p.92) This was the state of the law in 2016 at the moment of the protests. It is interesting that in a country with by far one of the strictest abortion laws in Europe, 85% of the population does not agree with any changes towards further criminalisation and almost 30% are in favour of liberalisation of the law (CBOS, 2016). So when the proposition of a complete abortion ban was being forwarded for further Parliamentary work with only 7% of population supporting the move (ibid.), this served as the immediate spark that ignited the waves of protests in 2016.

Why is it still important to talk about an event that took place 6 years ago?

Firstly, “Black Protest”, as this nationwide action was dubbed, was some of the biggest that the country has ever seen to date, involving roughly 150,000 people and actions in at least 142 cities and towns (Kubisa, 2017). Similar events were organised in cities all over the world. I dressed black that day, too (although for those who know me that’s nothing new) and joined a group of more than 100 people in Edinburgh city centre gathering in solidarity with our Polish sisters and siblings. The collective energy felt really strong and there was a feeling that we are a real extension of the crowds gathering in Poland.

Secondly, the energy and scope of the protests was unprecedented not only on the streets but also online, and the actions took place in many forms. The Black Protest was not a one-off event – it became a part of a movement under the name of All-Poland Women’s Strike (Ogólnopolski Strajk Kobiet) which continues to grow and change according to the needs of the cause. I have been observing the movement since its conception and find it fascinating how many people from widely different walks of life united under the symbolic black umbrella. A number of analyses of the Black Protest (Nacher, 2021; Korolczuk, 2016; Majewska, 2016) point to a massive role of social media in building the movement as well as their impact on the social sphere.

(Source: Author’s personal archive)

#BlackProtest no.1

The strike was inspired by a 1975 strike in Iceland when for one day most of the women took a day off to protest against gender inequality and gender pay gap. It was quite obvious that it was impossible to repeat the same level of popular engagement because of the precarity of many people’s work situation or caring responsibilities that prevented them from dropping everything and joining the picket lines. However, there were other forms of engagement that allowed people to join the protest in a way they deemed possible. Apart from traditional protest gatherings on the streets (let’s not forget these were counted in tens of thousands), citizens were encouraged to wear black to a workplace or school, place posters in the windows, take a black and white photo of oneself holding a card with a hashtag #blackprotest and post on social media, or engage online by liking, sharing and reacting to posts marked with the protest’s hashtags.

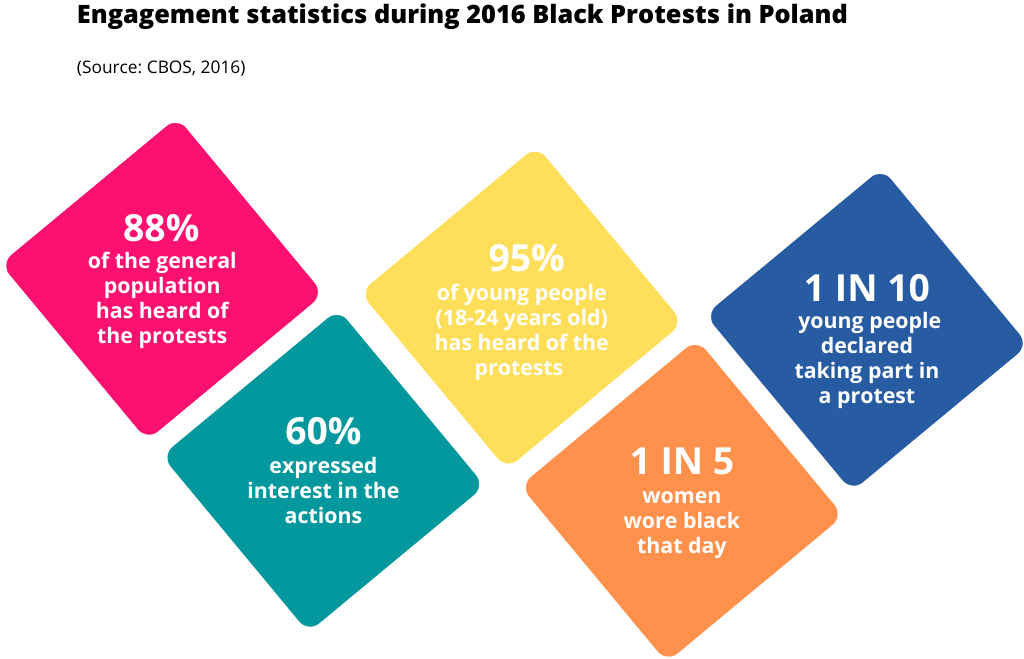

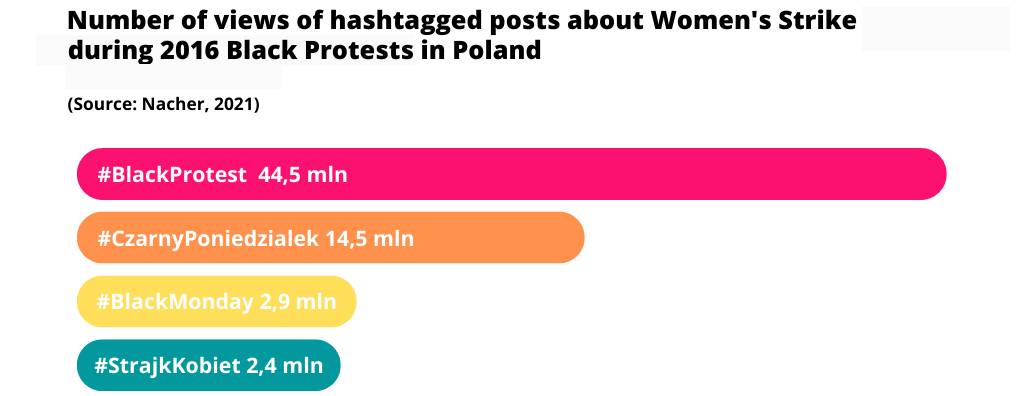

The engagement was higher than during any other protests and the protest was highly visible in a public sphere (see Fig.1). The protest was advertised online as a Facebook event to which 214,140 people responded. Considering that normally a Facebook event would engage about 10% of respondents offline, having an around 50% attendance rate is quite a success. Hashtags (Fig. 2) used across social media channels were in Polish and English, which encouraged an international community to take part and spread the news about what was happening. On 3rd of October 2016 for 9 hours #BlackProtest was placed in tenth place on Twitter’s Top20 World Trends, reached over 44.5 million users with more than 4.3 million interactions, and became the most powerful hashtag in Poland that year (Nacher, 2021, p.267).

The story continues…

The story did not end in 2016, unfortunately. After the October protests the government has rejected the anti-abortion bill, but this was only silence before the storm. In 2020, the Constitutional Court, with majority of pro-government judges, ruled abortion in case of fetal malformity unconstitutional in the vein of a pro-life agenda. This move practically banned 98% of previously permittable abortions and meant forcing pregnant people to carry unviable pregnancies, risking mother’s health and often life. Immediately, people’s anger renewed and slogans “Women’s hell”, “Get your rosaries off my ovaries”, “This is war” could be heard again, but this time even wider and louder. The 2016 protests have shown that collective action on such a scale is not only possible but also effective (Hall, 2019), so the next wave of protests engaged even higher numbers.

#BlackProtest no.2

I believe that the political awakening of those previously politically disengaged and the young people during the 2016 strikes had a massive impact on the second big wave of protests. They lasted from October 2020 until January 2021, even in the face of Covid-19 pandemic restrictions.

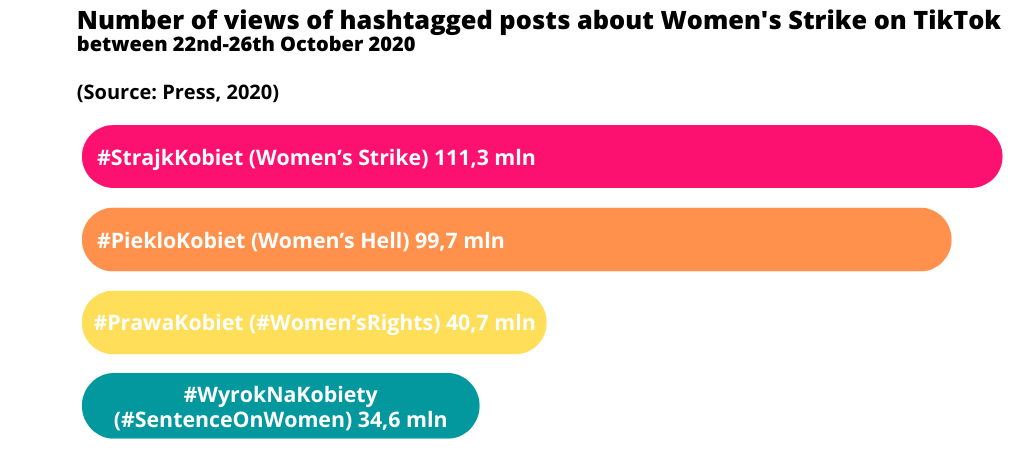

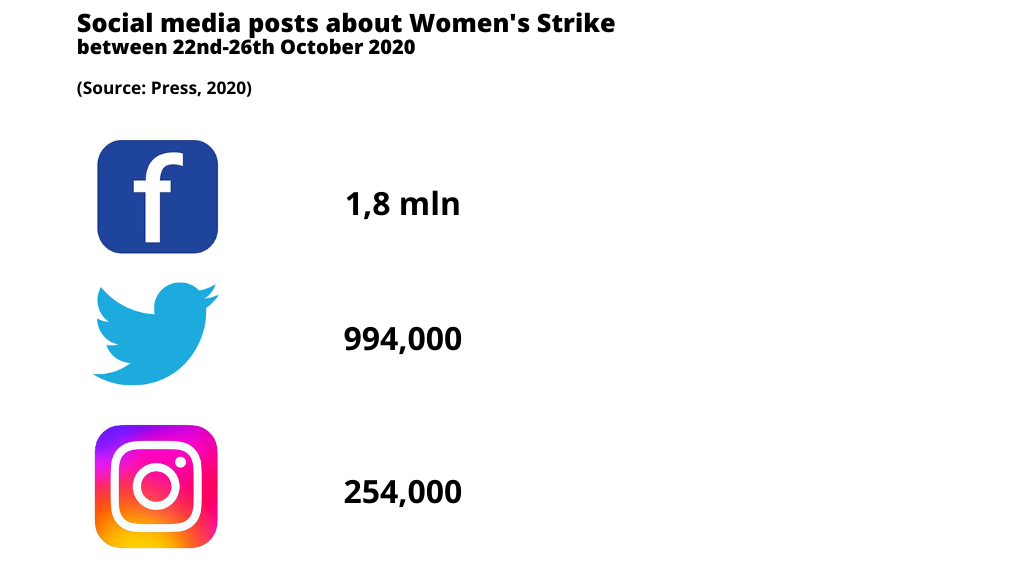

The street protests which had to follow social distancing rules were not easy to organise but still gathered the biggest crowds on the streets since the Solidarność strikes in the 1980s. The majority of protests took place on the 30th October 2020 with over 400,000 protesters attending in 400 cities and towns, tripling the 2016 numbers. Because of the restrictions small actions were much more widespread, i.e. holding banners while on a daily walk or waiting in a queue to a supermarket, wearing a facemask with a protest symbol of a red lightning bolt, or taking part in a car rally (Nacher, 2021). Ideas for actions were posted and shared via social media. Twitter, Instagram, Facebook and TikTok, were flashing black and red again (colours of the protest’s visual identity) and photographs of solidarity protests from across the world, together with corresponding hashtags, flooded the online sphere, with over 3 mln posts (see Fig. 4 & Fig. 5).

Access equals participation

Social media was useful not only for organising the protests, although this role should not be downplayed. The extension of social networks beyond the offline contacts allowed coalition-building (O’Donnell, 2018, p. 224) and creation of a massive protest network across the whole country from cities to villages reaching vast numbers of people and helping with communication. But more importantly, social media played a big role in ensuring accessibility and equality. The online space enabled wide participation for those who couldn’t attend the protests and every voice, hashtag or a picture carried the same weight and importance.

Online versus(?) offline

The 2016 and 2020 protests are a great example of how offline and online activism can go hand in hand and how the social media and on ground action cannot be clearly separated (Hall, 2019, p.1505). This shows that the idea of digital dualism, a term coined by Nathan Jurgenson (2011), based on an assumption that online and offline are two separate worlds, the offline world being real and online virtual, is becoming increasingly outdated..

Digital activism is often described with a derogatory term of slacktivism – a lazy non-committal clicking for a good cause (including posting, liking and sharing activist content). Zeynep Tufekci (2017), in a renowned book exploring digital activism “Twitter and Tear Gas”, argues against the idea introduced by Morozov in his book The Net Delusion that slacktivism is distracting people from real, productive activism. She observes that most people who become activists these days are actually exposed to the ideas online and the social networks are the best places for activist recruitment (ibid., p.18). Indeed, Dominka Kasprowicz from Strajk Kobiet says the campaign specifically embraced social media to effectively reach young people and keep them interested.

“I see the increased activity on the web as part of the continuum rather than separate from real-life endeavours. It seems that sharp criticism of digital activism as a failed promise stems in part from a failure to see digital activism as belonging to the online/offline continuum.”

says Nacher (2021, p.266).

She explains that living in a society dependent on technology, everything we do functions within code/space. The term describes “everyday life saturated with communication networks and the practices of data processing (including the use of social media platforms)” that “have been changing the conditions through which society, space, and time, and thus spatiality, are produced” (ibid., p.266).

Tufekci agrees that there is no reason anymore to separate the two spheres of offline and online, and adds that the actions should be looked at according to their capacities rather than the sphere in which they happen. She sees capacities not as measurable outcomes, but rather the longer lasting effects that social movements can bring. These can include: connective capacity, narrative capacity, disruptive capacity, and electoral and/or institutional capacity, as listed by Tufekci (2016, p.191). Online activism can be seen as an act of “weak resistance” (Majewska, 2016; Nacher, 2021, p.266), in opposition to heroic and revolutionary acts on the ground, however, there is nothing weak about it, as it can have an important narrative and connective capacity (Nacher, 2021, p.267).

Krakow university students and women’s rights activists and their supporters staged another anti-government protest in Krakow tonight, opposing the pandemic restraint to express their anger at the Supreme Court ruling that tightened the already stringent abortion laws.

On Sunday, November 1, 2020, in Krakow, Poland. (Source: Artur Widak/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

From a hashtag to community

Nacher dedicated the whole article to the power of a hashtag and its narrative capacity in context of the Women’s Strikes. A hashtag (together with the stories and/or images it is connected to) has a potential of gathering all ‘micro-messages’ under one umbrella. It can create “a space inclusive enough to accommodate different perspectives and different stories of motivation, determination and dissent, including coming out with sharing stories of undergone abortions or various instances of limited access to contraception”. It also helps with visibility of these “micro-narrations” (Nacher, 2021, p. 268) and that in turn enables construction of connective action. Connective action, characteristic to digitally networked society, allows forming loose public networks connected by a flexible and wide sense of collective identity (Korolczuk, 2016, p.100).

In the case of the Women’s Strike collective identity, one of the crucial components defining a social movement as per della Porta & Diani (2006, p.20), is not so obvious. The identities of the protesters cut across gender, age, and political stances and ethical values (ie. from supporters of a total liberalisation of the abortion laws on the left to supporters of the status quo who still sympathise with the ruling party), so it’s difficult to talk about a one shared identity in a conventional sense. Tufekci also notices that many networked protests do work outside of traditional social and political differences (2017, p.83). As Nacher (2021, p.268) and Tufekci (2017, p.111), Korolczuk also sees this being an effect of social media’s flexibility and being able to include many different voices and personalised actions (2016, p.100).

Conclusion

I did not have space here to talk about nuances of online activism (privacy and security issues, ownership of the media, etc.) and concentrated mostly on the positive effects that social media had on the 2016 and 2020 strikes.

With such a high participation and visibility the protests definitely changed the social sphere in Poland and some media called it a revolution. Firstly, they created a new shared protest culture that lives outside of this particular issue and translates onto other areas of social dissent. Secondly, the connection network built between people online as well as offline is not going anywhere, and it’s only growing bigger and stronger with each new campaign. And thirdly, they also had a power to change the narrative – the scale of the protests online and offline showed in a very visible way how big the support for the anti-abortion restriction movement actually is. And this brings a lot of hope for the future.

Postscriptum: Reflections on blogging

Taking part in this blog was my first experience of blogging. Finding the right language and tone of voice was quite challenging as we all needed to find a balance between personal and professional, accessible and informative, casual and academic. It was quite refreshing being able to add some personal views and stories to an otherwise more academic content, and I think this makes the text more lively and grounds it in a particular reality. I will try to incorporate personal stories in my future writing, obviously adjusting the scope of information and the tone of voice accordingly.

I started the exercise from a position of a hard social media and online activism sceptic, believing that only the collective on-the-ground, concrete action had power to change anything. However, in the course of the research while digging deeper into the world of online activism and new (or even not so new) thoughts and theories, I started to better understand the role of social media and digital tools in social change. In particular, I reflected more on the fallacy of digital dualism and started looking differently at intertwining online and offline spheres. It showed me how important it is to keep up with the most current thinking.

Writing the three blog posts was an interesting journey, moving from very general ideas and concerns to more specific examples, and on the way discovering an array of interesting literature exploring topics. I would not have thought of many of them before, ie. I did not expect that there would be academic literature about the role of hashtags in social media. The literature I came across made me think a lot more about the implications of social media activity on the idea of the self or the collective identity, something that is maybe only loosely connected with social change and development, but nevertheless it would be interesting to explore further on another occasion.

Thank you very much for reading to the end and I look forward to lively discussions directly on the post’s “Comments” section as well as on Facebook and Twitter. What do you think about the idea of digital dualism and its critique? Can a social movement function on a bigger scale without social media at all? Is there anything missing in the post that you would like to know about the Women’s Strike protests? Thank you in advance for the engagement!

References:

CBOS. (2016). Komunikat z Badań CBOS: Polacy o prawach kobiet, „czarnych protestach” i prawie aborcyjnym, nr 165/2016. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from: https://www.cbos.pl/SPISKOM.POL/2016/K_165_16.PDF.

Della Porta, D., Diani, M. (2006). Social Movements. An Introduction. 2nd Edition. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

Hall, B. (2019). Gendering Resistance to Right-Wing Populism: Black Protest and a New Wave of Feminist Activism in Poland? American Behavioral Scientist, 63 (10), 1497–1515.

Jurgenson, N. (2011, February 24). Digital Dualism versus Augmented Reality. Cyborgology in The Society Pages. Retrieved October 11, 2022, from: https://thesocietypages.org/cyborgology/2011/02/24/digital-dualism-versus-augmented-reality/.

Korolczuk, E. (2016). Explaining mass protests against abortion ban in Poland: the power of connective action. Zoon Politicon, 7, 91-113. https://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.element.desklight-d2218371-151e-413a-8bbc-d60a8cddc99d.

Kubisa, J. (2017). We Will Not Close Our Umbrellas! Retrieved October 12, 2022, from: https://obieg.pl/en/48-we-will-not-close-our-umbrellas.

Majewska, E. (2016). Słaby opór i siła bezsilnych. #Czarnyprotest kobiet w Polsce 2016. Retrieved October 9, 2022, from: https://www.praktykateoretyczna.pl/artykuly/ewa-majewska-saby-opor-i-sia-bezsilnych-czarnyprotest-kobiet-w-polsce-2016/.

Nacher, A. (2021). #BlackProtest from the web to the streets and back: Feminist digital activism in Poland and narrative potential of the hashtag. European Journal of Women’s Studies, 28 (2), 260-273.

Nowicka, W. (n/d). The Struggle for Abortion Rights in Poland. Sexpolitics. Reports From The Frontlines. Retrieved October 10, 2022, from https://www.sxpolitics.org/frontlines/book/pdf/capitulo5_poland.pdf.

O’Donnell, A., Sweetman, C. (2018). Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs, Gender & Development, 26:2, 217-229, DOI: 10.1080/13552074.2018.1489952

Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas. The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. London: Yale University Press.

Other hyperlinked websites

BBC. (2016, October 6). Poland abortion: Parliament rejects near-total ban. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-37573938.

Citizen Lab. (2020, May 20). ‘Slacktivism’: Legitimate Action or Just Lazy Liking? https://www.citizenlab.co/blog/civic-engagement/slacktivism/.

GenderIt.Com. Feminist Reflections On Internet Policies. (2021, January 12). Online protests against Poland’s abortion law become stronger. https://genderit.org/feminist-talk/online-protests-against-polands-abortion-law-become-stronger.

Guardian. (2020, October 30). Pro-choice supporters hold biggest-ever protest against Polish government. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/oct/30/pro-choice-supporters-hold-biggest-ever-protest-against-polish-government.

Guardian. (2019, September 18). The birth of Solidarity in Poland – archive 1980. https://www.theguardian.com/world/from-the-archive-blog/2019/sep/18/the-birth-of-solidarity-in-poland-archive-1980.

Guardian. (2011, January 9). The Net Delusion: How Not to Liberate the World by Evgeny Morozov – review. https://www.theguardian.com/books/2011/jan/09/net-delusion-morozov-review.

Ogólnopolski Strajk Kobiet. Facebook event page. https://www.facebook.com/events/1659773451018196/.

Ogólnopolski Strajk Kobiet’s social media pages:

Press. (2020, October 28). Protesty kobiet z rekordowymi zasięgami w sieci. https://www.press.pl/tresc/63722,protesty-kobiet-z-rekordowymi-zasiegami-w-sieci.

Resources on Gender Equality in Iceland. Women’s Day Off. Retrieved October 15, 2022, from https://kvenrettindafelag.is/en/resources/womens-day-off/.

The New Yorker. (2020, November 17). The Abortion Protests in Poland Are Starting to Feel Like a Revolution. https://www.newyorker.com/news/our-columnists/the-abortion-protests-in-poland-are-starting-to-feel-like-a-revolution.