Dear readers,

As I am writing this blog a 6-hour power cut has forced me to leave my house and walk to the nearest coffee shop with a power backup. I am lucky to not only live close to such a café (walking isn’t much fun when it’s 37 degrees outside) but to also have the funds to get myself something to drink in exchange for their generator-powered electricity. This power cut made me wonder, how is Simeon managing to be online and feed his followers with news today, and how are his followers able to access his channels without electricity. To make matters worse, WhatsApp was down for some time recently. I immediately jumped to the conclusion that this outage was only in Malawi, yet it was a worldwide one (it’s amazing how the mind works, isn’t it?).

When a WhatsApp breakdown turned into a meme war. Source:Twitter

In a previous blog post, I talked about the challenges digital activists face when it comes to international events such as the COP. In this blog article, I would like to take you to Malawi with me and see what challenges our young digital climate activist Simeon Kalua is facing not in an international but a national set-up.

The digital landscape in Africa and Malawi in particular

Generally speaking mobile phones and internet connectivity are an important part of the African landscape in the 21st century. Even in the most rural settings of the African countries I’ve been to namely Malawi, Benin, Tanzania, Niger, Togo, Uganda, Kenya, and Zambia, do people at least own mobile phones. I wanted to find out if my personal experience really reflects the reality of many. I, therefore, started my own research and came across Prof. Dr. Bruce Mutsvairo. He is working as a professor of humanities at Utrecht University and will be an important reference throughout this article.

Prof. Dr. Bruce Mutsvairo Source:Utrecht University

Why him? He has spent many years researching digital activism in Africa and has published multiple books in the process. But beyond that, he explicitly focused on Malawi in one of his studies about digital activism and the digital divide. This is such a great thing because there aren’t many studies about Malawi in general and especially not in the field of New Media and digital activism.

But let’s get back to my question about the digital landscape in Africa. In his book Digital activism in the social media era: Critical reflections on emerging trends in sub-Saharan Africa Mutsvairo makes the following statement about the use of mobile phones in Africa:

“The uses of mobile phones in Africa extend beyond voice communication, to include text messaging, photo and video, banking, citizen journalism, and, increasingly, accessing the internet. The latter, as this volume shows, is particularly important for engagement in political activities, democratic debate, and social activism. Social networks like Twitter and Facebook, as well as messaging platforms such as Whatsapp, have become crucial spaces for the expression of dissent, the mobilization of activists, and conduits to influence mainstream media agendas.”(Mutsvairo 2016:6)

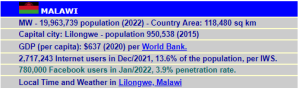

Now what this statement shows is simply how important not only access to a working mobile phone is but also to the internet, in order to engage in political activities. Simeon’s followers won’t be able to engage with him on the same level if they don’t have access to his social media channels, at least not if Simeon chooses to focus on digital activism. Like in many other African countries people in Malawi face serious problems especially when it comes to internet access and costs. (Mutsvairo 2017:150) High costs and difficult access, as well as high illiteracy rates, have led to less than 14% of the population using the internet.

Numbers don’t lie. Source: Internetworldstats

Understanding the digital divide in Malawi

In 2017 Mutsvairo and Ragnedda (Associate professor at Northumbria University), published a very interesting study. Over a period of 6 months, they followed the Facebook page of a well-known newspaper namely Malawi24 with the aim to understand the effect of the digital divide on digital activism in Malawi (Mutsvairo 2017:149ff) The digital divide is the difference between those that have access to ICT’s and those that don’t have the same access even whilst living in the same country. This can be due to internet availability, prices of data and mobile phones, income, education, or other forms of infrastructure. (Mutsvairo 2019; Norris 2001)

According to Mutsvairo, there are three stages of the digital divide. The first one focuses mainly on access to existing telecommunications infrastructures. Whereas the second level of the digital divide focuses more on the use and purpose, digital skills, and competencies, whilst the third level takes the social and cultural benefits into consideration. (Mutsvairo 2017:156f.) Given the fact that Malawi is one of the poorest countries in the world according to the World Bank, it is a fair question to ask how beneficial a focus on the digital landscape is for many Malawians but let’s start with the first stage of the digital divide.

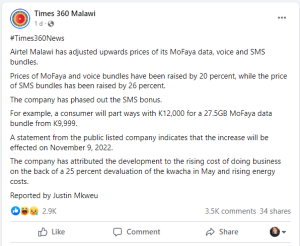

Unarguably the digital landscape in Malawi ticks all the boxes for the first stage of the digital divide. Less than 14% of the population with access to the internet, and on top of that high data prices are making it even more difficult for many people to access the internet. In fact, there was even a campaign about high data prices in Malawi in 2020. In this particular case Airtel Malawi, one of the biggest telecommunication service providers reacted with a slight decrease in data prices.

It was a great initiative but unfortunately, Airtel Malawi just announced (as of 04th of November 2022) that they will raise data prices again due to the instability of the Malawian economy.

Higher data prices will limit the access to internet further for many Malawians. Source: Facebook

When Mutsvairo and Ragnedda were following the Malawi24 Facebook page it became clear that as much as discussions were political and users were actively engaging with each other, they did not make a collective claim or formed any kind of organized activism. On top of that most discussions, as well as posts were in English, which makes it close to impossible for many Malawians to engage on a deeper level. (Mutsvairo 2017:156) As much as English is the official language in Malawi only 26% of the population above the age of 14 speak and understand English.

What does that mean for digital activism in Malawi?

Digital activism is a form of activism that involves the use of digital tools such as social media channels, the internet, and of course mobile phones. By using those tools and channels activists aim to bring social change and make their voices heard. The effect of the digital divide, even in the first stage of it, on digital activism is big.

“There are noble prospects for digital activism in Malawi but first internet access has to be made cheaply and readily available for citizens and apart from affordability, the quality of life for the majority of the population needs to drastically improve so as to curb potential digital inequalities.”(Mutsvairo 2017:160)

If we go back to our main protagonist Simeon and his digital activism we can agree that access to the internet (stage one of the digital divide) is crucial for his digital activism. It is the first step that needs to be taken, but at the same time, the observations by Mutsvairo and Ragnedda show that access alone isn’t what drives digital activism forward. Simeon’s followers need to have the skills to engage and they need to see a real benefit in it for them. In essence stages two and three of the digital divide. It is one thing to generate likes but it is a completely different level of engagement to have people reinvest what they see online into their social lives.

Digital activism in Malawi a way forward

So what is the way forward for digital activism and youth activists such as Simeon in Malawi? How can he make sure his voice is being heard and reaches his followers so that they want to change their personal lifestyles? Does he even stand a chance to spread his message and engage people online? We all know there is no simple answer to these questions and there are many possible solutions. What’s clear is that according to Brunce people like Simeon are “[…] important civil society actors within Africa, who are utilising new media to engage with the global public sphere. One important – and under-studied – group are youth. Irreverent youth culture – both by ordinary Africans on the continent and in the diaspora – contributes to online political culture with real effects and, in doing so, creates new forms of African modernity.” (Bunce 2016:191f)

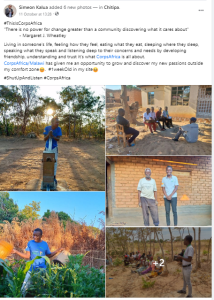

But for Simeon to actually create a new form of African modernity he can’t simply leave behind people without internet access. Therefore in a country like Malawi, clearly struggling with digital inequality it is still the best way to use digital activism complementary to interacting with people directly and in the offline world. Kenyan activist Gichinga said it right when she stated that one can’t work online without working offline at the same time and that a conversation about serious topics such as climate change doesn’t start online but rather continues there.

As much as Simeon is a digital activist he also is an activist in the offline world. He interacts with communities and schools on a daily basis and uses his digital activism to continue the conversations he has started offline. This is why I see so much potential in the work Simeon is doing and it’s also why I chose him to be the protagonist of my blog instead of other already famous African climate activists like Vanessa Nakate who has a vast follower basis already. I believe Simeon is just at the beginning of his journey and so is Malawi when it comes to the huge potential online activism has in store for it and the social media channels that can be used for digital activism.

Facebook for example offers a free mode allowing users to see text only without any data charges, which is a good way of avoiding high data costs. If you wonder what’s in it for Facebook, the Guardian published an article about that some years back, With time hopefully the digital divide will shrink and channels such as TikTok will help Simeon and his followers to interact with each other and beyond their social bubble. Because TikTok not only empowers its users to feel connected but also helps them engage with like-minded users through symbolic resources such as soundtracks and viral dances. (Literat and Kligler-Vilenchik, 2019).

Online and offline activist Simeon Kalua. Source: Facebook

As this blog post marks the end of our university assignment I would like to reflect a bit on my personal experience being a blogger. But before I do so, please let me know what you think about the digital divide in Malawi, online activism, and my suggestion for a way forward. Would you be interested to hear how other countries have managed to overcome the digital divide and how they engage people through online activism? Also, how did you like my more academic approach in this blog post compared to my previous posts? I am looking forward to your thoughts in the comment section.

What blogging meant to me

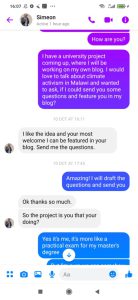

As a first-time blogger being part of the New Media Activism has been an exciting experience for me. Writing about what goes through my mind and triggers me itself was already a colourful journey, full of diverse research sessions to get the information needed through various channels even like Facebook Messenger.

How it all started. A private conversation between Simeon and me. Source: Facebook Messenger

I really wanted to do something different, and do my part towards adding a little bit more colour to the very white blogging landscape that I am used to on an everyday basis. So I told myself: Nathalie, you can’t change who you are but why not use whom you can reach and the technical skills you have and do your part to support young African activists to move in the only direction possible, forward and not backward? So it became clear to me that I wanted to talk about Youth Activism in Africa, specifically in Malawi as I am based here. I also wanted to combine it with something that is related to my work, as I have most of my contacts through my work environment, and over the last years I met inspiring people so why not feature one of those? And so my blog got narrowed down to Youth Activism in Africa/ Malawi around the topics of climate change and permaculture. I was on a mission to use my blog for curating. In essence, I wanted to feature a young activist from the global south in my blog which is how Simeon Kalua appeared in my Inbox.

So far so good, but then the big challenge was to somehow link what was going through my mind with what is going through my fellow students’ minds in Singapore, Australia, Jordan, and Scotland. How do you meet when 8:30 pm in Malawi is 6 am in Australia and then you have a job, kids, and a life to navigate at the same time? In the end, it was the mixture of personal and professional contexts that made this blogging exercises such a diverse experience for me. Did I mention that I was the IT Guru of this group, which means I set up this website but that my dear reader is a story for the next blog post.

References (don’t forget all the links in the text)

Bunce, M., Franks, S., & Paterson, C. (Eds.). (2016). Africa’s media image in the 21st century : From the heart of darkness to africa rising. Taylor & Francis Group.

Literat, I., & Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2019). Youth collective political expression on social media: The role of affordances and memetic dimensions for voicing political views. New Media & Society, 21(9), 1988–2009

Mutsvairo, B., & Ragnedda, M. (2017). Emerging political narratives on Malawian digital spaces. Communicatio: South African Journal for Communication Theory & Research, 43(2), 147–167.

Mutsvairo, B. (Ed.). (2016). Digital activism in the social media era : Critical reflections on emerging trends in sub-saharan africa. Springer International Publishing AG.

Mutsvairo, B. & Massimo Ragnedda. (2019). Mapping the Digital Divide in Africa : A Mediated Analysis. Amsterdam University Press.

Norris, P. (2001). Digital divide : civic engagement, information poverty, and the Internet worldwide. Cambridge University Press.