Dear readers,

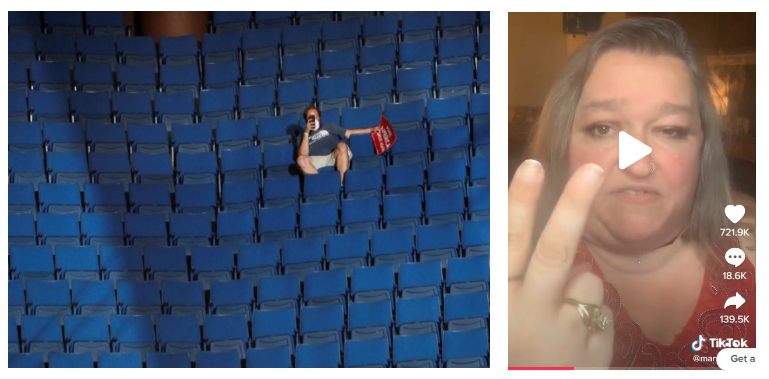

in June 2020, one blurry and unsophisticated TikTok video by a 51-year-old #TikTokGrandma (Laupp, 2020; Magid 2020), derailed Trump’s campaign rally in Tulsa, Oklahoma, when it went viral and mobilised people to falsely register for the stadium event, leaving a majority of the event’s seats empty. In the same year, the #blacklivesmatter hashtag went viral (Janfaza, 2020) on TikTok amplifying Police brutality.

There are already numerous notable examples (Hagaman, 2020) of ways activism, represented by collective actions, social movements and revolutions, (Tufecki, 2017, p.xix) has changed history around the world, including civil rights reform across the United States (1950s and 1960s), the anti-war movement and the anti-apartheid movement. But the onset of digital connectivity in the twenty-first century, particularly through social media, has reshaped how movements connect, organise, and evolve (Tufekci, 2017, p.xix). Social media platforms have been commended for their potential to provide new opportunities to fight injustice and oppression and support poor and vulnerable populations, particularly in the Global South.

The onset of social media(1) (Burns, 2017, p6) has given individuals more opportunities to create a safe space to gather and protest (Clark-Parsons, 2018, p2127; Coe, 2018, p511). Protesters can photograph, video, hashtag, post, like and share on social media. Social media content was prominent in the anti-government Arab Spring movement in the early 2010s, (Jamali, 2014), Occupy Wall Street movement in 2011 (Suh, Vasi, & Chang, 2017, p.291) and the #Metoo movement in 2017 (Manikonda, Lydia & Beigi, Ghazaleh etc al, 2018, p2) and the recent women’s rights protests in Iran (Kohli, 2022).

Until recently, these activities have been predominantly captured by users on the world largest (and seemingly indispensable) social media platform Facebook (and its purchased sub-sites Instagram and Whatsapp), as well as Youtube and Twitter (Tufecki, 2017, p.134; Kaye, DBV, Chen, X, & Zeng, J. 2020).

It may seem surprising that TikTok, a playful short-form video app, first used to produce a never ending stream of lip sync and dancing videos for entertainment (Iqbal, 2022), had found fame and purpose amongst social movements and for political expression (e.g., Literat and Kligler-Vilenchik 2019 & 2021; (Vijay & Gekker, 2021, p.3). Its rise in popularity globally means it now reaches more than a billion people in 155 countries in 75 languages (Iqbal, 2022). This substantial digital footprint justifies further exploration of TikTok as a potential vehicle championing social change.

This essay will take an in-depth look at how TikTok has engineered commercial virality and discuss the ways social movements can be empowered to create original narratives to amplify their messages and engage larger and diverse audiences. It will also highlight its weaknesses and why activists should remain vigilant, as social media’s privately-owned mega companies have effectively taken over previously held physical ‘public spaces’ where a majority of the globe communicate. This analysis will share examples highlighting TikTok’s failure to enforce policies and provide protection for its users. Foreign ownership of TikTok also poses significant security threats which warrant further discussion.

Understanding social media’s role in social movements and collective action is complicated, nuanced and difficult to summarise (Noble, 2018; Tufecki 2017; Literat 2018). This essay will expand on Zaynep Tufecki’s analysis of protest in the era of Facebook and Twitter in ‘Twitter and Tear Gas’ (2017), by applying some of her key learnings to TikTok.

TikTok: just how big is its reach?

First, we must understand TikTok’s tremendous potential to reach and influence the planet’s largest generation ever: Generation Z (McCrindle, 2022), aged 16 – 24 and comprising 30 percent of the world’s population. As the first ‘fully global generation’, Gen Z has made TikTok its social media app of choice, rapidly propelling its growth during extended periods of COVID-19 isolation (Midson-Short, 2022). It has been utilised in many movements, including the Schools Strike for Climate in 2019, the ongoing Black Lives Matter, #MeToo and for marriage equality.

Chinese-owned TikTok is the ‘new kid on the block’ in the social media market. The international version of Chinese app Douyin was launched globally in mid 2018 by internet company ByteDance. In four years, it amassed over 3 billion downloads and engaged one-third of all social media users globally (Dean, 2020). Facebook and Instagram took a decade to generate the same-sized user base.

How can TikTok support digital activism?

TikTok, like Facebook, provides multiple functions that are indispensable for social movements (Tufecki, 2017 p138). When TikTok users sabotaged a Trump rally (Magid, 2020), it highlighted the application’s capacity to provide visibility, empower and disrupt(2) (Tufecki, 2014).

The Trump rally example also illustrated how social media can provide the ability to scale movements up quickly using digital infrastructure to organise, coordinate, mobilise and share information. Platforms like TikTok are user-friendly, cost-effective as and less time consuming (Thompson, 1995) than traditional forms of offline protest and enable protesters to come together, share ideas, and organise actions to create unity for a cause (Maryville University, 2019). The Arab Spring and Occupy Wall Street events showcase the effect of such social movements at a global scale. A study of the latter movement (Suh et al., 2017, p291) found social media accounts accelerated the diffusion of the Occupy protests and highlighted their importance as a resource for activists:’ they represent a new medium to transform incidents of repression into mobilising opportunities’. Others have noted social media can help promote democracy and free markets and create new kinds of global citizens (Aday, Farrell, Lynch & Sides et. al., 2010).

Importantly, social media movements utilise platforms such as TikTok to: get access to large and potentially loyal, like-minded audiences without relying on traditional media; to gain multiple ways to interact and connect intimately with users; and provide tools to develop new narratives to gain public attention, mobilise audiences and create transformative and concrete change (Powell, 2022).

TikTok is famous for attracting and maintaining its audience, serving up a seemingly endless stream of short addictive videos (average length is 21-34 seconds and up to 10 minutes). The site’s algorithm (famously known as its black box) (Kelly, 2022) heavily mines its users’ data (what you follow, comment on, scroll past or stay on) and uses everything it knows to then appeal directly to users with bespoke content (and advertisements) to keep them scrolling for hours.

Like other social media sites, TikTok, creates the perfect environment to promote a fundamental pattern in human relationships – the need to belong. Homophily (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, & Cook, 2001; Tufecki, 2017, p.9), where people seek people who think like them to draw social support, is made easy in a globally networked site which provides intimate connections between users.

TikTok effectively supercharges homophily by enabling a culture where users are enticed to add their voice to the latest trend or social movement. Hashtags, in particular, have become a central way for social media users to connect to existing topics, to gain visibility for their own expression, to draw public attention, and to engage to coordinate shared action (Thorson, Edgerly, Kliger-Vilenchik, & Xu et al., 2016).

TikTok also empowers the user’s sense of agency through ‘shared symbolic resources’, which youth employ to promote political expression, in particular, to engage and connect with like-minded audiences (Literat & Kligler-Vilenchik, 2019, p.2)which make them feel good. TikTok-specific elements like viral dances and popular soundtracks are shared symbolic resources, as well as “physical (MAGA hats), visual (the closed fist for the Black Lives Matter movement) or hashtags (#alllivesmatter) (Literat & Kligler-Vilenchik, 2019, p.15). These resources, along with TikTok’s algorithm enable activists to deliberately connect with like-minded people with similar beliefs in a ‘life affirming space’ where mistrust of electoral and institutional options is a cultural goal (Tufecki, 2017, p77).

A key aspect of TikTok’s success in distinguishing itself from competitors, is how it ‘circumscribes creativity’ (Kaye et.al 2020). Essentially TikTok empowers ordinary citizens to become creators by offering standard video templates (Zubtitle, 2022)(3), tools or guides that allow seamless creation and to capitalise on popular trends. Unlike other social media platforms, this allows users to duplicate popular formats for themselves with the push of a button (Vijay & Gekker, 2021, p.2).

As a dynamic outlet for creative expression, TikTok is effective at mobilising people in social movements, especially young users who creatively mix the political and the personal (Literat & Kligler-Vilenchik, 2021). During the 2016 American election, youth were lip-syncing speeches by Trump or Obama (earnestly and sarcastically from both sides of politics). This playful political engagement (through dance, satire and parody etc) has shown to democratise politics and evoke participation from audiences that are conventionally hard to reach (Hartley, 2010, p10), an important feature for digital activists looking to expand their audiences.

To generate more content and build in virality, TikTok constantly offers users suggestions for content creation and focuses heavily on promoting localized content at a global scale (Geyser, 2020). It highlights local trending pages and hashtag search filters and hosts large scale country-specific in-app challenges such as #1MAuditionTikTok (TikTok, 2019). It is constantly innovating a vast catalogue of tools (sound effects, music, filters, etc.) to keep users engaged. As TikTok offers such a novel suite of creative tools and content, it attracts a diverse and broad audience.In particular, marginalised groupshave used social media to connect, share experiences, of oppression, and contest the status quo (Jackson, Bailey & Welles, 2020, p123). This is a salient feature for digital activists looking to augment their support base.

#TikTokfails: Greed, censorship, discrimination, exploitation and security

Can the digital technology afforded by TikTok guarantee social movements’ success in making change?

When this is discussed in academic circles, Tufecki (2017) says there’s concern people will align with “technodeterminism”—the simplistic and reductive notion that after social media was created, their mere existence somehow caused revolutions to happen. She points out there is no binary answer: humans or technology, it’s more nuanced than that: ‘technology influences and structures possible outcomes of human action, but it does so in complex ways and never as a simple, omnipotent actor’.

Noble (2021) explains that we have more data and technology than ever before in our daily lives and ‘more social, political and economic equality and injustice to go with it’. She urges people to think of data in more complex ways to reveal how it’s used to oppress, discriminate and undermine civil and human rights. This certainly applies to TikTok. While it offers digital activists and social movements some strengths and real benefits, a closer analysis reveals significant weaknesses, risks and dangers, to individual users and society as a whole.

It might appear that TikTok’s tools are ‘free’ and of significant benefit for users. The reality is TikTok is part of a $150 billion global business (Iqbal, 2022). Its infrastructure is heavily monetized, collecting user’s data and using it to generate profits by selling tailored advertising on the platform, much like its competitors.

TikTok is heavily reliant on what’s been dubbed the ‘influencer economy’ (Cunningham & Craig, 2019a, p67). Kaye (et al. p6) explains it leans on influencers and other micro-entrepreneurs, to produce creative content, attract traffic and produce revenue. All parts of the platform are commodified, from user activities, to social relations and transactions, through to targeted advertising. Fuchs & Trottier (2013, p34) describe this seemingly innocuous form of commodification by platforms as ‘internet play labour [sic] where the audience barely recognises they are engaging in labour, but create economic value’. Users become part of the ‘attention economy’, because they need to pay, receive and seek the attention of others to amplify content and succeed. In 2020, influencers, could earn more than USD$20,000 (Abidin, 2020, p1) per post and up to $5 million a year for working the ‘attention economy’ on TikTok (Goldhaber, 2006; Abidin 2020 p1).

So, why does this matter to social movements?

Tufecki explains (2017) that over the past two decades massive centralised, private and profit driven social media platforms including TikTok own the world’s most valuable troves of user data, control the user experience, and wield the power to decide winners and losers for people’s attention by making small changes to their policies and algorithms. They have taken over the traditional public space where visibility is often determined by an algorithm produced by a business prioritising its business model. Tufecki says when supersize ’corporations own public space and use it for profit no one is assured of freedom of speech or privacy’ (2017, p137), or guaranteed their rights will be respected. A recent examples are TikTok influencers complaining about ongoing bullying and harassment on the platform, with some receiving death threats for supporting abortion, novel videos and selling candy. They say the algorithm prioritises emotion and angry reactive videos are given priority: ‘If your face is bright red or your eyes are welling up, people will stop scrolling and you’ll get more views’ (Harwell & Lorenz, 2022).

Tufecki (2017, p129) says social media platforms are within their legal rights to block content as they see fit. This means a world in which social movements can potentially reach hundreds of millions of people after a few clicks without having to garner the resources to challenge or even own mass media, but it also means that their stories can be silenced by a terms-of-service complaint or by an algorithm. TikTok’s algorithm is a big challenge for social movements because it can filter and prioritise content, with significant consequences.

There is evidence that TikTok has down-weighted the posts of BlackLivesMatter protestors (Molina, 2020), political dissidents (Protest and Dissent in China, 2021), LGBTQ+ people, disabled people (Hern, 2019), and certain African-American hashtags (Wikipedia Contributors, 2019). TikTok’s explanations for this vary, ranging from attempting to protect users from bullying to algorithmic mistakes (Censorship on TikTok, 2022).

To drive profits, large private social media companies use minimal staffing to monitor billions of users on their platforms (Tufecki p143). Facebook and TikTok rely on community policing, which means the company only acts on policy violations if it’s reported. It is a distinct disadvantage for activists because social movements often advocate on politically sensitive issues, making them an easy target for community reporting. In addition, media has reported that content monitoring decisions are being out-sourced to low-paid workers in countries like the Philippines, who must review lots of content under strict time restrictions (Tufecki, 2017, p152).

An example of TikTok unethically profiteering was discovered by a 2022 BBC investigation (Gelbart et al., 2022), which found displaced families in Syrian camps are begging for donations on TikTok while the company takes up to 70% of the proceeds. The BBC claimed the families involved were engaged by livestreaming agencies, who are contracted on commission by TikTok to help content creators produce more appealing livestreams(4).

In addition to censorship, the foreign ownership of TikTok by Chinese company ByteDance is controversial. Leaked internal documents about TikTok’s content moderation guidelines in China indicate that it adheres to Communist Party requirements and censors content critical of the socialist system or the government (Hern, 2019). In 2020, President Trump called it a national security threat and tried to ban it and in 2022, the United States House of Representatives recommended lawmakers delete the app for similar reasons (Wikipedia Contributors, 2022). Cybersecurity experts in Australia (Mason, 2022) analysed TikTok’s source code and reported it aggressively harvests excessive amounts of data beyond what’s necessary for the application to function(5). Handing over swathes of data to an undemocratic regime makes individuals and countries vulnerable. TikTok could be exploited in the way other social platforms have been to spread disinformation or promote and influence elections, like what occurred with Facebook and Cambridge Analytica (Chang, 2018) where the data of 87 million users was exposed and made available to Trump’s political campaign.

This essay asked: Is TikTok a fad or a crucial tool for digital activism? TikTok’s sophisticated and multi-layered algorithm offers real benefits to social movements. As an accessible, mainstream creative outlet, TikTok has tremendous potential to mobilise and empower young people to connect, create content and build support for a cause. It gives digital activists potential to interact with an immense and diverse audience in multiple ways, something essential to gain public attention and the momentum needed to create historic social change. Measuring how effective TikTok is in achieving this is nuanced and difficult to do, given the complexity of how technology influences and structures outcomes of human actions.

We can say with certainty that TikTok is not intended to be a catalyst of social change. Some users have harnessed its reach to create or amplify social movements, but the app’s heavily commercialised and concealed for-profit structure highlights its owner’s corporate greed, and its failure to invest in measures to protect its users have led to censorship, discrimination, profiteering, bullying and harassment, with little recourse for those affected. TikTok and other digital tools mask and deepen social inequality, and this is something we are only just beginning to understand (Noble, 2018, p1) and articulate.

With its growing popularity and wealth, TikTok will continue to dominate the social media scene, and there’s little incentive for it to reform. Digital activists must be wary of TikTok’s foreign ownership, as it has the potential to exploit users and put their safety and wellbeing at risk for profit or political reasons.

Lessons Learned

I really enjoyed the opportunity to further explore TikTok, a social media platform I initially laughed at and dismissed due to its users’ seemingly impulsive, shallow and narcissistic tendencies. I was definitely anti-TikTok, and I think this bias came about because, unlike Facebook, it’s a platform I haven’t grown up with. I’m a Millennial, not a Centennial and we Millennials don’t really use TikTok or understand it. I was intrigued as to why so many young people were engaging with it despite the gargantuan effort required to film, edit and post videos.

Further research showed TikTok’s sophisticated fast-paced algorithm is quite impressive. It offers valuable tools to support creativity, connection and amplification to a vast audience. However, these are just tools to keep users engaged and online for longer periods of time to support TikTok’s business model. It’s clear TikTok’s priority is its cash flow, designed to squeeze every dollar possible from its users, alarmingly without many of them knowing it. What I’ve found absolutely terrifying is just how few protections are in place for individuals, who not only experience discrimination, but who are also exploited and mined for data by TikTok, with its unfettered access to users’ personal data. It’s just staggering that billions of youth freely give away this information, apparently unaware of the risk of their data potentially being made available to an authoritarian superpower, a significant security risk in Australia, where I live. Personally, the pitfalls of using TikTok far outweigh the benefits. While TikTok can support social movements, I’m confident in saying there’s no way using TikTok guarantees the success of any social movement nor any positive social outcomes for individuals, movements or society broadly.

I will be deleting my TikTok accounts after this assignment. That’s probably my biggest lesson: nothing is for free, remain wary of colossal corporations infringing on your space and rights without any means of appeal and lobby your government for more protections.

Footnotes

- Burns describes social media as ‘Internet-based platforms that allow users to create profiles for sharing user-generated or curated digital content in the form of text, photos, graphics or videos within a networked community of users who can respond to the content’.

- When the video of just one politically engaged Iowa woman calling for a false registration ticket drive went viral amongst K-pop fans and youth, it pranked Trumps’ campaign into believing it had one million ticket requests and only

- To use trending sounds or hashtags, to lip-sync, record a reaction or tutorial or do a ‘TikTok Challenge’.

- After the BBC contacted TikTok for comment, the company banned all of the accounts and declined to say how much it takes from gifts.

- For example, it checks device locations hourly, continuously requests access to contacts even if the user originally denies, maps a device’s running apps and all installed apps

References

Abidin,C.(2020).Mapping Internet Celebrity on TikTok: Exploring Attention Economies and Visibility Labours. Cultural Science Journal,12(1) 77-103. https://doi.org/10.5334/csci.140

Aday, S., Farrell, H. Lynch, M., Sides.J, Kelly, J. Zuckermann.W (2010): Blogs and Bullets: New Media in Contentious Politics. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace

Burns, K.S. (2017). Social media : A reference handbook: a reference handbook. ABC-CLIO, LLC.

Censorship on TikTok. (2022, October 21). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Censorship_on_TikTok#cite_note-:0-1

Clark-Parsons R. (2018). Building a digital Girl Army: The cultivation of feminist safe spaces online. New Media & Society, 20(6), 2125–2144. doi:10.1177/1461444817731919

Chang, A. (2018, March 23). The Facebook and Cambridge Analytica scandal, explained with a simple diagram. Vox. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2018/3/23/17151916/facebook-cambridge-analytica-trump-diagram

Coe, A.‐B. (2018). Practicing Gender and Race in Online Activism to Improve Safe Public Space in Sweden. Sociol Inq, 88, 510–534. https://doi.org/10.1111/soin.12220

Cunningham, S., & Craig, D. R. (2019a). Social media entertainment: The new intersection ofHollywood and Silicon Valley. University Press.

Cunningham, S., Craig, D., & Lv, J. (2019b). China’s livestreaming industry: Platforms, politics,and precarity. International Journal of Cultural Studies, 22(6), 719–736.https://doi.org/10.1177/

Dean, B. (2022, January 5). Tiktok User Statistics (2022). Backlinko. Retrieved September 5, 2022, from https://backlinko.com/tiktok-users#tiktok-user-demographics

Fuchs, C., & Trottier, D. (2013). The Internet as surveilled workplayplace and factory. In S.Gutwirth, R. Leenes, P. de Hert, & Y. Poullet (Eds.), European DATA Protection: Coming ofage (pp. 33–57). Springer Netherlands.Gamson, W.A., and G.Wolfsfeld. 1993. Movements and Media as Interacting Systems.”The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 528:114–25.

Gelbart, H., Akbiek, M., & Al-Qattan, Z. (2022, October 12). TikTok profits from livestreams of families begging. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-63213567

Geyser, W. (2022, August 3). What is TikTok? – everything you need to know in 2022. Influencer Marketing Hub. Retrieved October 5, 2022, from https://influencermarketinghub.com/what-is-tiktok/

Goldhaber, M. (2006). The value of openness in an attention economy. First Monday, 11(6). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v11i6.1334

Hagaman, S. (2020, August 4). 9 powerful Social Change Movements You Need to Know about. Amnesty. Retrieved September 12, 2022, from https://www.amnesty.org.au/9-powerful-social-change-movements-you-need-to-know-about/

Hartley, J. (2010). Silly Citizenship. Critical Discourse Studies, 7(4), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405904.2010.511826

Harwell, D., & Lorenz, T. (2022, October 23). Sorry you went viral. Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/interactive/2022/tiktok-viral-fame-harassment/

Hern, A. (2019, September 25). Revealed: How TikTok censors videos that do not pleaseBeijing. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/sep/25/revealedhow-Tiktok-censors-videos-that-do-not-please-beijing

Hern, A. (2019, December 3). TikTok owns up to censoring some users’ videos to stop bullying. The Guardian.https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2019/dec/03/tiktok-owns-up-to-censoring-some-users-videos-to-stop-bullying

Iqbal, M. (2022, August 19). Tiktok revenue and Usage Statistics (2022). Business of Apps. Retrieved September 14, 2022, from https://www.businessofapps.com/data/tik-tok-statistics/#:~:text=TikTok%20reached%20one%20billion%20users,by%20the%20end%20of%202022.

Jackson, S. J., Bailey, M., & Welles, B. F. (2020). #HashtagActivism: Networks of race and gender justice. Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology Press

Jamali, R. (2014). Online Arab Spring : Social Media and Fundamental Change. Elsevier Science & Technology.

Janfaza, R. (2020, June 4). TikTok serves as hub for #blacklivesmatter activism | CNN politics. CNN. Retrieved September 12, 2022, from https://edition.cnn.com/2020/06/04/politics/tik-tok-black-lives-matter/index.html

Jenkins, H., Ford, S., & Green, J. (2013). Spreadable media: Creating value and meaning in a networked culture. New York University Press.

Kaye, DBV, Chen, X, & Zeng, J. 2020. The co-evolution of two Chinese mobile short video apps: Parallel platformization of Douyin and TikTok. Mobile Media & Communication, Online first: 1–25. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1177/205015792095212

Kelly, H. (2022, January 24). TikTok privacy settings to change now. The Washington Post. Retrieved September 30, 2022, from https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2022/01/24/tiktok-privacy-settings/

Kohli, A. (2022, October 8). What has happened in Iran since the death of Mahsa Amini. Time. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://time.com/6220853/iran-protests-mahsa-amini-what-to-know/

Kranzberg, “Technology and History: ‘Kranzberg’s Laws,’ ” Technology and Culture 27, no. 3 (1986): 544–60, doi:10.2307/3105385

Laupp, M. J. (2020, June 14). Mary Jo Laupp #TikTokGrandma on Tiktok. TikTok. Retrieved September 12, 2022, from https://www.tiktok.com/@maryjo.laupp/video/6837311838640803078

Literat, I., & Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2019). Youth collective political expression on social media: The role of affordances and memetic dimensions for voicing political views. New Media & Society, 21(9), 1988–2009. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819837571

Ma, L., & Zhang, Y. (2022). Three Social-Mediated Publics in Digital Activism: A Network Perspective of Social Media Public Segmentation. Social Media + Society, 8(2). https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051221094775

Magid, L. (2020, June 22). How a 51-year-old grandmother and thousands of teens used TikTok to derail a Trump Rally & Maybe save lives. Forbes. Retrieved September 12, 2022, from https://www.forbes.com/sites/larrymagid/2020/06/21/how-a-51-year-old-grandmother-and-thousands-of-teens-used-tiktok-to-derail-a-trump-rally–maybe-save-lives/?sh=38e2d57b1a9b

Manikonda, Lydia & Beigi, Ghazaleh & Kambhampati, Subbarao & Liu, Huan. (2018). #metoo Through the Lens of Social Media. 10.1007/978-3-319-93372-6_13.

Maryville University. (2019, November 25). Social Media as Activism and Social Justice. Maryville Online; Maryville University. https://online.maryville.edu/blog/a-guide-to-social-media-activism/

Mason, M. (2022, July 17). TikTok’s “alarming”, “excessive” data collection revealed. Australian Financial Review. https://www.afr.com/policy/foreign-affairs/tiktok-s-alarming-excessive-data-collection-revealed-20220714-p5b1mz

McCrindle. (2022, October 27). Gen Z and gen alpha infographic update. McCrindle. Retrieved September 16, 2022, from https://mccrindle.com.au/article/topic/generation-z/gen-z-and-gen-alpha-infographic-update/#:~:text=Generation%20Z%20are%20the%20largest,almost%202%20billion%20of%20them.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415-444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

Midson-Short, D. (2022, June 19). What is TikTok? why is it so popular? Brandastic. Retrieved September 15, 2022, from https://brandastic.com/blog/what-is-tiktok-and-why-is-it-so-popular/

Miller, D., Costa, E., Haynes.N., McDonald,T., Nicolescu, R.,Sinanan.J, Spyer.J. , Venkatraman.S., Wang.X. (2016). How the World Changed Social Media. 10.2307/j.ctt1g69z35.

Molina, B. (2020, June 2). TikTok apologizes after claims it blocked #BlackLivesMatter, George Floyd posts. USA TODAY. https://www.usatoday.com/story/tech/2020/06/02/tiktok-apologizes-after-claims-blocked-george-floyd-posts/3122296001/

Noble, S.U., 2018. Algorithms of oppression. In Algorithms of Oppression. New York University Press.

Obar, J. (2014). Canadian Advocacy 2.0: A Study of Social Media Use by Social Movement

Groups and Activists in Canada, Canadian Journal of Communication, 39(2), 211–233.# doi:10.22230/cjc.2014v39n2a2678. SSRN 2254742.

Ozkula, S. M. (2021). What is digital activism anyway? Social constructions of the “digital” in contemporary activism. Journal of Digital Social Research, 3(3), 60-84. https://doi.org/10.33621/jdsr.v3i3.44

Parthasarathi & Kumari, G. 2021, “The Role and Impact of Social Media on Online Social Movements: An Analysis of ‘ALS Ice Bucket Challenge’ in India”, Journal of Media Research, vol. 14, no. 1, pp. 102-119.

Powell, C. (2022, March 22). The Promise of Digital Activism—and its Dangers. Retrieved September 18, 2022, from

https://www.cfr.org/blog/promise-digital-activism-and-its-dangers-0.Protest and dissent in China. (2021, July 7). Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Protest_and_dissent_in_China

Safiya Noble. (2021, September 28). Www.macfound.org; MacArthur Foundation. https://www.macfound.org/fellows/class-of-2021/safiya-noble#searchresults

Suh, C., Vasi, B. & Chang, P. (2017). How social media matter: Repression and the diffusion of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Social Science Research, 65, 282–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.01.004

Thompson, J. B. (1996). The Media and Modernity: A Social Theory of the Media. Stanford University Press. Retrieved from http://www.sup.org/books/title/?id=2348

Thorson, K., Edgerly, S., Kligler-Vilenchik, N., Xu, Y., & Wang, L. (2016). Climate and sustainability| Seeking visibility in a big tent: Digital communication and the people’s climate march. International Journal of Communication, 10, 23.

TikTok. (2019, August 16). Tiktok announces the seventh edition of the 1 million audition. Newsroom. Retrieved November 5, 2022, from https://newsroom.tiktok.com/en-in/tiktok-announces-the-seventh-edition-of-the-1-million-audition

Tufekci, Z. 2014, “Social movements and governments in the digital age: evaluating a complex landscape”, Journal of International Affairs, vol. 68, no. 1, pp. 1-XVI.

Tufekci, Z. 2017: Twitter and Tear Gas-The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Uldam, J. (2018). Social media visibility: Challenges to activism. Media, Culture & Society, 40(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717704997

Vijay, D., and A. Gekker. 2021. “Playing Politics: How Sabarimala Played Out on TikTok.”

American Behavioral Scientist 65(5):712–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002764221989769

Wikipedia Contributors. (2019, February 11). African Americans. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/African_Americans

Wikipedia Contributors. (2022, March 6). Donald Trump–TikTok controversy. Wikipedia; Wikimedia Foundation. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Donald_Trump%E2%80%93TikTok_controversy

Wikimedia Foundation. (2022, September 12). Social Media and the arab spring. Wikipedia. Retrieved September 13, 2022, from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Social_media_and_the_Arab_Spring

Zubtitle. (2022, September 23). 6 best types of videos to make on Tiktok. Zubtitle.com. Retrieved October 5, 2022, from https://zubtitle.com/blog/6-best-types-of-videos-to-make-on-tiktok