The following blog post is the end-product of several weeks of engaging with the news of the protests in Iran for human rights throughout this blog, within the context of the theme ‘New media activism and development’. It must be noted that at the time of writing, the protests in Iran are still ongoing and the following are my own observations based on the limited information available from news sources. The following post is further informed by academic reading, including Zeynep Tufekci’s Twitter and Tear Gas, and Hopkins’ UN Celebrity It girls as Public Relation-ised Humanitarianism, to explore the role of digital activism on a local and global scale, referring to the protests in Iran as a case study.

New Media: A Digital Stage

People in Iran are not unfamiliar with internet censorship. Social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter and Telegram were banned in Iran following the 2009 presidential election and the 2019 November protests (Newsroom, 2022). As platforms that enable communication with people across time and space, social media platforms contribute to the construction of collective identities and support communication and organisation around protest movements (Cammaerts, 2015).

ICT supported communicative practices enable the following in the context of protest movements:

- Internal organisation, recruitment, and networking

- Mobilise and coordinate direct action

- Disseminate movement frames independently of the mainstream,

- Discuss/debate/deliberate/decide

They also enable people to challenge ideological enemies, surveil the surveillors and preserve protest artefacts (Cammaerts, 2015).

Internet blackouts, therefore, have become a ‘go-to’ for the Iranian authoritarian government as a means to control the flow of information, limit communication among the people, and thereby attempt to cripple any people-led protest movements.

The most wide-sale internet shutdown in Iran occurred during the 2019 November protests and was “the most severe disconnection tracked by NetBlocks in any country in terms of its technical complexity and breadth” (Newsroom, 2022). The weeklong internet block contributed to the isolation of the country from the rest of the world during which the initially peaceful protests were met by violent crackdowns by the regime, resulting in the death of hundreds of people (Watch, 2020).

Most recently, the same tactics have been used during the widespread protests in Iran, in response to the death of Mahsa Amini in police custody for the improper wearing of her hijab. Although there has not been a complete internet blackout as in the case of protests in 2019, the government has repeatedly shut down mobile internet connections and disrupted social media services, including Instagram and WhatsApp, two of the most popular services in the country (Burgess, 2022). Such widespread internet blocks have almost become synonymous with rising death tolls, as referenced in the popular usage of the phrase “the internet is down, and they are killing the people” by protestors and activists seeking to raise awareness of events abroad.

The almost complete blackout of the internet in Iran during such protests contributes to the creation of a clear distinction and division between activists and activism within the country, and global activism abroad.

Local Digital and Collective Activism

Modern civil movements rely heavily on online platforms and digital tools to organize and generate publicity, and activists can generate their own media and campaigns. Importantly they can circumvent state censorship (Tufekci, 2017, p. xiii). Internet blackouts and restrictions, however, can cripple communication within such movements – so how are the protests in Iran ongoing, how are they maintaining their momentum, and how far is new media involved?

When the protests began in September 2022, video footage and photos of the protests, of women removing their hijabs and the destruction of images of Iran’s Supreme Leader were communicated widely by phone and internet (Butcher, 2022). Within a day, a quarter-million Instagram users had joined a digital chain of Iranians posting about Mahsa Amini, and the hashtag bearing her name had been tweeted, retweeted or liked more than nine million times (Yee, 2022). The news spread across Iran, reaching the Persian-speaking diaspora and the rest of the world, and people responded, calling for justice. The role of ICT’s in such circumstances is to bear witness to events and to communicate information. Advancements in technology, and the fact that almost everyone has a smartphone enables everyone to take photos and videos at the click of a button, contributing to the rise of citizen journalism, which I briefly explored in a previous blog. As protests spread across the country, the government cracked down on internet access; WhatsApp, Signal, Viber, Skype and Instagram were blocked (Butcher, 2022), impacting people’s ability to coordinate and exchange information on the ground.

Nevertheless, in a surveillance state such as Iran, where social media is censored and the activities of people monitored online, this may have proved to be a benefit to the protestors, in the sense that no identifiable de-facto leader or location could be identified (Tufekci, 2017). No individual could be targeted and silenced, arrested or eliminated, and a lack of identifiable leaders has also potentially prevented friction between the de-facto leaders and people who can voice their opinions through online platforms (Tufekci, 2017). With no single identified leader, the weight of the protest and its strength comes from the collective identity of the people and rests with every single individual, which is why, as our guest in the podcast stated, protests can be sparked anywhere at any time, sparked by an individual action that is soon joined by people nearby. Protests are an opportunity for self-expression, as Tufekci also argues, people want to belong and add their voice to the collective (pp. 88-90).

As such, people in Iran have expressed their voices both online and on the streets, but not without risks; Iranian celebrities, journalists and activists were targeted and arrested for their activities online and in public.

New Media for Collective Voice

Shervin Hajipour, a 25-year-old Iranian singer, was one such celebrity arrested for his song ‘Baraye’. In my previous post, Viral Song as Vehicle for Voice, I explored how several tweets from Iranian people who have conveyed their desires for change are combined with music to create an audio-visual emotive piece that transcends borders. According to Caitlin M. Bentley, visual methods can empower individuals to challenge customary assumptions and to change prevailing social and political structures (2019, p. 477). I would argue that this can also apply to audio formats, as the song ‘Baraye’ quickly became an ‘anthem’ for the ongoing protests in Iran, thereby helping to articulate and solidify a cultural and collective identity among Iranians, Kurds, and other ethnic minorities (p. 481). The visual and auditory nature of the music video, therefore, enabled marginalized members of the Iranian population to contribute, through tweets, to the formulation of a collective identity.

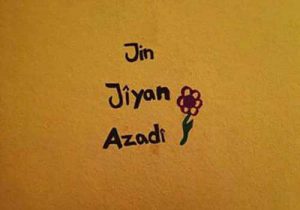

Furthermore, as was explained to us by our special guest in our podcast, the slogan which has been used throughout the ongoing protests Zan, Zandegi, Azadi (Woman, Life, Freedom) and are the closing lyrics of the song, was originally coined by Kurds in Turkey as Jin, Jîyan, Azadi. This is an additional layer to the song which helps tell the story of Mahsa Amini, a Kurdish Iranian woman, through the lenses of the marginalized, of women and ethnic minorities in Iran, who have been discriminated against, and promotes “their recognition as human beings who deserve respect (p. 484).

Furthermore, as was explained to us by our special guest in our podcast, the slogan which has been used throughout the ongoing protests Zan, Zandegi, Azadi (Woman, Life, Freedom) and are the closing lyrics of the song, was originally coined by Kurds in Turkey as Jin, Jîyan, Azadi. This is an additional layer to the song which helps tell the story of Mahsa Amini, a Kurdish Iranian woman, through the lenses of the marginalized, of women and ethnic minorities in Iran, who have been discriminated against, and promotes “their recognition as human beings who deserve respect (p. 484).

Challenges to Digital Activism

The internet blackouts in Iran have been a draconian and drastic measure taken by the government in Iran, however, news of the protests still reached the rest of the world and the people have continued to express themselves through graphics, photos, videos, and music. A more effective countermeasure to the protests would perhaps have been the spreading of misinformation, doubt, confusion, online harassment, and distraction (Tufekci, p. xxviii). Such challenges within the networked public sphere, along with algorithms on social media platforms that control visibility can be used by governments to maintain the status quo (Tufekci, p. xxix).

Global Activism and Celebrities

As has been addressed, in the context of Iran, people involved in the protests are facing considerable danger and even risk their lives to make themselves heard and bring about social change on the ground. There is also a significant diaspora of Iranians and Persian-speaking people who have picked up the cry of people in Iran and ensured they continue to be heard across the world even in the face of internet blackouts.

The globalization and communication of such movements is important for the international community to be informed and engaged, to keep authorities accountable, and challenge events. Individuals such as celebrities with large social media followings can significantly contribute to raising awareness of the challenges that marginalized people face and advocate for their rights. In previous posts by my fellow students, it has been addressed how women around the world have cut their hair publicly in solidarity with women in Iran (here) and how celebrities have used their social media reach to engage their following regarding what is happening in Iran (here).

I would however here like to expand on how there is also the risk that individuals can use such civil movements for personal gain, creating an international image of themselves, ensuring the limelight remains on them and their activities, rather than the protests and the challenges the people seek to address.

As public figures, celebrities have an image to uphold, and news around them and about them is carefully framed to raise their public image. As Hopkins explores in the case of UN celebrity ambassadors, these celebrities can raise awareness of issues like global gender equality while simultaneously profiting from gendered norms and stereotypes in their roles as ambassadors (2018, p. 274). Unfortunately, the framing of news stories in humanitarian celebrity women’s magazines often exclude the voices of the marginalized women and over-emphasise wealthy, white celebrities as contemporary female role models, while ignoring or simplifying complex problems like domestic violence and gender inequality (p. 274).

Popular media in the west can therefore shape the relationship between people in the West with the foreign ‘other’, thereby influencing politics and the way in which the international community engages with humanitarian issues in other countries (p. 274).

Concluding Reflections

As a communication and development officer working in the Middle East, it has been an educational experience observing and keeping up to date on the events in Iran, both in a professional and academic capacity. Reading various academic sources that have not been directly relevant to the on-going developments in Iran or women’s rights movement but have explored the role of social media and digital media has challenged me to think about the role of new media during these protests and consider how the current protests differ from others, such as the Gezi Park protests in Turkey, and the Tahrir Square protests in Egypt.

I do not believe that the protests in Iran have been tied to any particular location, instead, I believe that the battleground for human rights in Iran is being fought on and through women’s bodies. The women are embodying the movement and collective identity, as demonstrated by removal of their hijabs and the public cutting of their hair. With each woman and young girl that is killed, the protests flare up again, further increasing dissatisfaction among the people with the government.

Throughout this blog post, I have expanded on the two previous pieces I wrote, as well as addressed new points of interest that were raised during my additional reading. I’m grateful to have been able to spend so much time dedicated to understanding the situation in Iran and observing how the women-led protests developed over time. The themes we addressed on this blog; human rights, women’s rights, activism, digital media, and social media platforms, have all been relevant to my work as a communications and development officer and I hope to apply the new insights I have gained to my critical and strategic thinking at work.

I am deeply grateful to have been part of a fantastic team in which each individual carried their own weight, contributed with their strengths, and showed patience and support when I needed it. Creating this blog has been an intensive and time-consuming process that I could not have handled by myself.

Bibliography

- Burgess, M. (2022, 9 23). Iran’s Internet shutdown hides a deadly crakdown. Retrieved from WIRED: https://www.wired.co.uk/article/iran-protests-2022-internet-shutdown-whatsapp

- Butcher, M. (2022, 10 5). As Iran throttles the internet, activist fight to get online . Retrieved from Techcrunch: https://techcrunch.com/2022/10/05/iran-internet-protests-censorship/

- Caitlin M. Bentley, D. N. (2019). ‘‘When words become unclear’’: unmasking ICT through visual methodologies in participatory ICT4D. AI & Society, 477–493.

- Cammaerts, B. (2015). Social Media and Activism. LSE, 1027-1034.

- Hopkins, S. (2018). UN celebrity ‘It’ girls as public relation-ised humanitarianism. the International Communication Gazette, 273–292.

- Newsroom, I. I. (2022, September 26). Iran to continue Internet ban, grand access to regime insiders, . Retrieved from Newsroom, I.I: https://www.iranintl.com/en/202210268565

- Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas – the power and fragility of networked protest . New Haven : Yale University Press.

- Watch, H. R. (2020, 11 17). Iran: No Justice for Bloody 2019 Crackdown. Retrieved from Human Rights Watch: https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/11/17/iran-no-justice-bloody-2019-crackdown

- Yee, V. (2022, 09 29). Desite Iran’s efforts to clock the internet, technology has helped fuel outrage. Retrieved from New York Times : https://www.nytimes.com/2022/09/29/world/middleeast/iran-internet-censorship.html