While spending the past few weeks trying to understand how the use of social media is shaping a fourth wave of feminism I have found myself increasingly interested in what this means for those who do not have access to the online platforms, tools, skills, or strategies that propel women’s rights movements in a new media landscape.

While the fourth wave of feminism is described as increasingly intersectional, is the central role that new media plays in the strategies employed undermining the pursuits of justice for those marginalised in relation to technology?

This blog is going to look at women’s activism in India as a digitally emerging country (Guha, 2021:68). India has millions of active social media users, and millions of people without access to the technology, literacy, and digital skills needed to make one’s voice heard on these platforms. I will reflect on how different the experience of advocating for one owns rights and justice is for those who have access to social media compared to those who don’t – traditionally poor and marginalised women often living in rural communities with high levels of gender inequality and gender-based violence.

I will build on Tufekci’s (2017) framework for analysing movements based on their ability to build and signal capacity. They suggest that “[s]trength of social movements lie in their capacities: to set the narrative, to affect electoral or institutional changes, and to disrupt the status quo (Tufekci, 2017:191).

What I am particularly interested in here is what methods or tools of protest and activism that is available to whom and what capacities these different methods signal. I will investigate the ways in which the distribution of signalling power both challenges and reinforces existing structures of inequality and marginalisation in Indian society.

The growth of social media feminism

Arguably social media has given many women across the world a platform to be heard as they speak out about personal experience of abuse and injustice as well as systemic forms of oppression.

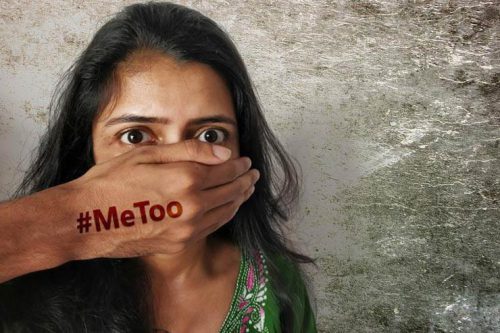

As I’ve reflected on before, when women share their personal experience on social media using viral hashtags like #MeTooIndia, #EverydaySexism, or #LoSHA, seeing the sheer number of people who evidently have similar experiences is impactful. The question is what that impact is.

Does it mainly serve to reassure and perhaps soothe victims of harassment or violence that they are not alone, reduce feelings of guilt or shame as they situate their own trauma in a bigger picture, all in order to deal with and eventually move beyond their personal experiences? Or, does it prompt organised response to systemic issues?

Neo-liberal feminism shaped on and by social media

Saraswati (2021) suggests that feminist activism on social media is generally carried out within a neo-liberal framework. This means, among other things, that the discourse tends to be centred on the individual, rather than the collective. The objective of this activism is generally focused on the individual ‘victim’s’ healing and/or the individual perpetrators’ shaming (Jain, 2020:10; Saraswati, 2021:32;109;71). Less so on specific strategies for addressing the societal flaws that enable widespread gendered abuse (Saraswati, 2021:112).

Saraswati also reflects throughout their book on how social media, perhaps particularly visual platforms, encourages and/or rewards good neoliberal subjects who are appealing, inspiring, and entertaining (2021:1) and how this excludes people whose characteristics do not fit the neoliberal selfie mould and/or are unwilling or unable to heal and speak out about their abuse in an empowered manner (2021:122-3).

Many of us engage with, or consume, social media in a rather solitary manner, largely consisting of one-way interactions. It’s important to recognise that we interpret other’s content based on our own references and experiences. This means that there is a big risk that the voices of a relatively privileged majority drown out or even undermine those of marginalised groups. Saraswati reflects on this in how white women fail to recognise and acknowledge the racialised pain reflected on in one of rupi kaur’s poems, claiming the message as theirs (Saraswati, 2021:51).

If the main way in which we engage with feminist activism is by consuming content on social media to facilitate our own personal healing, concerns about slacktivism are not unfounded as such engagement may support the shaping a (predominantly neo-liberal) feminist narrative but fail to signal organisational and institutional capacities needed to take on the status quo.

However, there are also examples of movements where social media has played an important role in coordinating offline movements, framed social and political agenda setting and led to positive outcomes for individuals and society at large. In India these include #IWillGoOut which successfully coordinated protests against sexual harassment and violence against protests across India in 2017 (Titus, 2018:234), #LahuKaLagaan, a movement that led to the removal of a 12% tax on sanitary pads in 2108 (Jain, 2020:5), #MeToo which resulted in the strengthening of legislation on sexual harassment in the workplace (Jain, 2020:6).

#MeTooIndia

In India, as in many places around the world, the #MeToo movement brought to light historical cases of sexual harassment and violence that had previously been swept under the rug in order to protect powerful men at established institutions. Guha shares a number of stories of women journalists working in Indian news media who had been harassed by senior male colleagues and either chosen not to report, or reported but found themselves demoted, fired, or harassed to the extent that they resigned (2021:102-6). For some of these women, including Nasreen Khan – a friend of Guha’s, the #MeToo movement led to widespread recognition of their experience and in some cases justice for their perpetrators.

Once free of the ‘old-media gatekeepers’, who had at best ignored and at worst carried out their abuse, these skilled journalists and writers were able to utilise social media platforms and signal their capacity to the extent that both individual men and the patriarchal system at large was reviewed.

Despite the initial, promising, outcomes of the #MeToo movement in India mentioned above, long-term, and widespread change has been limited. Guha reports that a panel on sexual harassment and abuse set up in October 2018 in response to the movement, was quietly dissolved without ever submitting any report (2021:98). Meanwhile many of the powerful men ‘cancelled’ during the movement are back in positions of power.

I argue that this showcases how the viral online and in person #MeToo protests signalled strong enough capacities to trigger reviews of both individual cases and legislations. The movement did not however have the capacity required to keep pressuring the government and other institutions once the initial virality of the movement died down. My analysis aligns with Tufekci’s argument that because social media generally makes it easier to protest (online) and to coordinate in person protests many of the structures and stamina required to deliver lasting societal change are not developed at scale, hence many movements fizzle out after initially burning very bright (2017). Jain comes to similar conclusions and suggests that this is related to cyberfeminism being more reactive than offline movements which they suggest are more proactive (2020:10). Looking at reactive protest movements there is arguably some merit to their claim.

Outrage against rape spurring on legislative change

When Jyoti Singh was brutally raped and murdered on a bus in Delhi in 2012 the outrage on social media was immense and reached beyond both Delhi and India. #Delhibraveheart was used by millions in support of Jyoti and her family (Jain, 2020:5). Much of the social media outrage after her death was focused on just that, expressing horror, grief, and support for the victim; and call for harsh punishments of the perpetrators. This aligns with the individualised shaping of online protest I’ve touched on before.

However, the sympathy and shaming were also accompanied with reflections on India’s wider problem with ‘rape-culture’ and need for a cultural and legislative shift. These calls for change were loud both on social media and in the many in person protests that took place across the country. Jyoti’s tragic faith had become a symbol for a systemic problem, much like the rape of a woman called Mathura by a number of police officers in the 1970s. Following Mathura’s rape widespread protests erupted and eventually led to legislative changes (Guha, 2021). Similarly, India’s rape laws were reviewed and amended following protests after Jyoti’s death. The definition of rape was expanded, and punishments increased not only for rape but crimes like stalking and acid attacks too (Guha, 2021:85; Jain, 2020:5).

These two examples, four decades apart, suggest that there has been and still is power in the signals sent by mass protest using new and old media strategies and in person rallies. The question I will tackle next is who has the capacity to deploy such tactics, and what is the experience of those who don’t.

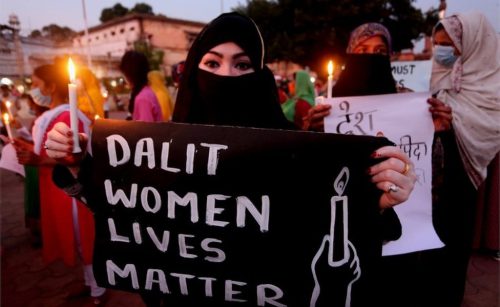

The exclusion of marginalised women

While millions of Indians have access to social media, even more to internet and smartphones – India became the largest smartphone market in the world in 2016 (Titus, 2018:240), the use of these digital tools is unequally distributed across the country (Subramanian, 2015: 76). Poor, rural women are the least likely to use social media platforms for a range of reasons, including internet access and literacy. In 2018 only 30% of Indian women had internet access (Jain, 2020:8).

This means that the many positive aspects of using social media in feminist activism, including the ability to quickly organise petitions and marches like the #IWillGoOut campaign (Titus, 2018), swift dissemination of knowledge (Jain, 2020:3), direct feedback and consultation processes (Subramanian, 2015:73), and ability to anonymously express and explore one’s experiences and identity (Subramanian, 2015:74), are not readily available to millions of Indian women.

For grassroots organisations and individual activists working in poor communities in India social media is not the game changer that the movements discussed in this blog suggests. Rather, it is an additional sphere of society and influence from which marginalised groups are excluded. As/if social media becomes increasingly important for how movements are shaped, protests organised, and activists connected, lack of access to (or knowledge of how to utilise) social media results in continued exclusion.

Guha (2021) shares a story of a young girl in a remote region of India who was raped by a local politician. For a long time, she and her family fought fruitlessly for the politician to be brought to justice. Only once the girl’s father had died in police custody and she in desperation attempted self-immolation did the story garner some of the media attention that the family believes is required for the young girl to receive the justice she deserves.

This story reminds us of the important role Guha (2021) argues throughout her book that old media still has in shaping the Indian public discourse. And it more specifically illustrates how limited the tools are for a relatively poor family in a rural province of India trying to raise awareness of and achieve justice against rape. The girl’s ability to be heard and seek justice was lacking to the extent that she felt required to pursue the very strongest of signals – signalling that she was willing to die a painful death in order to have her perpetrator face justice, and for herself to escape the torment she was experiencing.

The existence of social media channels for theoretical self-expression did not serve this young woman. This is of course a result of her not having access to or engaging with them. But also that the issues that tend to result in significant new media coverage is often very similar to what was and is covered in old media. Many of the large movements discussed in this blog were sparked by violence and harassment targeted at relatively privileged women, women with relatively strong voices and/or whose faiths were traditionally newsworthy.

In conclusion…

Old media still plays a very important role in India. It’s one of the few countries in the world where printed newspaper distribution is increasing. And while in much of the Global North social media has come to heavily influence traditional media as well, this isn’t as clearly happening in digitally emerging countries. Instead for activists and movements to reach the mainstream they need to strategically use both old and new media.

This continues to put traditionally marginalised people and grassroots organisation at a disadvantage. The issues they work on are less likely to be seen as newsworthy by the gatekeepers of old media, and they lack the resources and skills needed to utilise new media.

What I have gained from the research I’ve carried out for this blog is that for Indian women with comparative power and privilege, social media can provide the signalling power they need for their strives to be acknowledge and for personal justice to be enacted. But for long term systemic change in a deeply patriarchist society with huge inequalities, movements largely shaped on social media tend to lack the capabilities and sustainability required. And, for the poorest and most vulnerable, the increasing power of social media is arguably a symbol for the continued exclusion and marginalisation of their voices.

Bibliography

- Guha, P., 2021. Hear #metoo in India: News, Social Media, and Anti-Rape and Sexual Harassment Activism. Rutgers University Press.

- Jain, S., 2020. The rising fourth wave: feminist activism on digital platforms in India. ORF Issue Brief, 384, pp.1-16.

- Saraswati, L.A., 2021. Pain Generation: Social Media, Feminist Activism, and the Neoliberal Selfie. New York University Press.

- Subramanian, S., 2015. From the streets to the web: looking at feminist activism on social media. Economic and Political Weekly, pp.71-78.

- Tufekci, Z., 2017. Twitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protest. Yale University Press.

- Titus, D., 2018. Social media as a gateway for young feminists: lessons from the# IWillGoOut campaign in India. Gender & Development, 26(2), pp.231-248.