An honest reflection on what is happening in the (online) world

Introduction

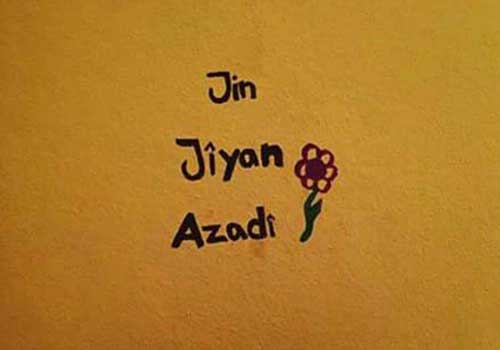

For the past weeks, Iranians have been fiercely protesting against the regime of their government. This was sparked by the death of Mahsa Amini, a 22-year old Iranian woman, who was arrested for ‘inappropriate attire’ and was beaten to death for it. The demonstrations have been mainly led by young women who refuse to accept restrictive laws such as hijab requirements (Bushwick, 2022). The onset of the Iranian demonstration this year found lots of support through social media platforms, such as TikTok, Facebook and Instagram. The news of Mahsa Amini was spread extremely quickly and protesters received the attention and support of social media users from all over the world.

We see here a movement of media that supports activism and social development, a movement that is far from being new but still very unknown in its nature. There are many pros and cons when it comes to using social media and technology for activism. However, the main goal was and will always be; social change. This article discusses the pros and cons of media in regards to activism.

Online activism: a threat or a blessing?

Collective actions, revolutions and social movements are integrated into the human history (Tufekci, 2017). They have been studied thoroughly and for good reason too, because they change history (Heeks, 2017). People gathering to demand action, attention and change have helped to shape the world for centuries. Whether it is about the social actions that lead to social revolution, as seen in France, Russia, and China, to a change in regime as seen in Tunisia in 2011 and Ukraine in 2013. Social movements will no doubt continue to exists, but they now operate in a new terrain: in the online world. We are now digitally connected which reshapes how movements evolve, connect and organize during their lifespan (Tufekci, 2017).

With the rise of social media, a new tool was introduced to organize those social movements and activism. The digital world offers a potential for the angry and passionate to connect, convert and recruit into violence and activism. It also offers an environment to fight such violence. The digital world makes it possible for activists to take action, which creates real change in the courtrooms of the world (O’Donnell & Sweetman, 2018).

The dangers of social media activism

However, with these new digital possibilities for social activism, we also need to recognize the factors that might be limiting or dangerous regarding the digital world. We see challenges in structural inequalities, censorships in the form of internet blockage and removing and filtering information that is found online, and the misusage of big data by governments and big companies to nudge people in a direction that is beneficial to a certain group.

Inequality: not just in real life

The developments that we now see in Iran shows the fight for women’s rights and the movement of feminism underneath it. Accompanied with hashtags such as #WomanLifeFreedom, social media encourages a bigger playing field, allowing women’s voices from a wider array of background and countries, with or without traditional power, to be heard.

These feminist movements are part of a bigger topic, namely structural inequalities in the real (and online) world. While colonialism first existed in the brutal overtake of countries and cultures by white people, it is now seen in the digital world as well, with a clear dominance of white, male, straight and global North. Gender, race, and class are all critical factors responsible for limiting who has access to technology and who has a voice and is been heard on the internet (O’Donnell & Sweetman, 2018). We can see those challenges represented in movements like the #MeToo, where the impact of a viral conversation about gender-based violence is currently being felt in many places worldwide, at local, national, and global levels (O’Donnell & Sweetman, 2018).

Internet blockage: the new censorship

Another factor that need to be recognised is the power dynamics of governments, big companies or a powerful group protecting their status. With the internet’s chaotic nature, with too much information and weak gatekeepers, it can empower governments by allowing them to develop new forms of censorship based not only on blocking information, but on making available information unusable (Tufekci, 2017). This is of course not new, considering that before the rise of social media activism, all mass communication (radio, television, and newspapers) were controlled by the government and therefore (easily) censored.

Following this, the new censorship nowadays is internet shutdowns and the removal of important information online. Shutting down the internet has been a tool used by governments more than once in history. We saw it during the Egyptian revolution, were the government applied resistance in the form of a total shutdown of the internet. Under the rule of Hosni Mubarak, internet censorship and surveillance were severe. However, although Mubarak had shut down the internet – except a single ISP; the Noor Network – and all cell phones just before the “Battle of the Camels,” protesters had pierced the internet blockade within hours, and remained in charge of their message, which was heard around the world, as was news of the internet shutdown (Tufekci, 2017). On top of that, the resistance from the governing regime back then only concluded more anger.

We also saw it during the Syrian war, were events and attacks were documented by many Syrian people and published online. This time, Youtube took it down because the videos were, according to their policy, too aggressive and too visual. Ironically, Youtube is filled with videoclips that might actually be more aggressive. The question that raises is who actually benefits from erasing these videos, because essentially, it is erasing history.

And now, very recently, Iran blocked the internet in response to the activism on social media as a result of the death of the young woman. When the protests started to become more violent and more aggressive, the Iranian government protected themselves and their actions they did against the protesters by making it impossible to share videos on social media. They paralyzed the country and were praying that by doing so, people might just move on and forget what happened. It was not the first time that the Iranian government blocked the internet during protest against their regime. In 2019, the shutdown of the internet allowed the security forces in Iran to kill at least 300 men, women and children during five days of protests. To this day, no official has been held accountable for the unlawful killings.

The United Nations Human Right Committee has declared that states must not block or hinder internet connectivity in relation to peaceful assemblies (Heeks, 2017). However, states are increasingly doing this; states such as Sudan, Myanmar, Belarus, Venezuela, and Ethiopia have limited or blocked access to the internet. In Iran, as elsewhere, not only did the shutdown restrict access to information for people inside the country, it also stopped them from being able to share information with the rest of the world, thus obstructing research into the human rights violations and crimes committed, the identities of the perpetrators and the victims, and the real number of deaths (Tufekci, 2017).

Big data

Social media activism requires people to connect and organize themselves online in order to make impact. Governments surveil at large scale – which means that they can exactly know who will show up at a protest which happened in the United States, in Gezi Park (Tufekci, 2017). The data that becomes available by interacting online is treated as something that belongs to companies and governments, making it easy to manipulate behavior or nudge people, often toward profitable outcomes for the companies and not the individuals. On top of this, we can expect even more advancements in algorithms and artificial intelligence in the face of increasing power of companies and governments (O’Donnell & Sweetman, 2018). The rights of the individual, the long-term social impacts of these systems and their consequences do have a need to be discussed.

Conclusion: can social activism rely on social media or is it just a ‘handy’ tool?

Social media in regards to activism is a handy tool. It is a tool that helped Egyptian people to organize and to face the regime. But it is also a tool that erased the videos and memories and documentation of the Syrian conflict. The question we all must ask is if social media is a reliable tool for long-lasting activism or if it is merely a tool to be used for sharing and documenting. Social media is prone to unequal power dynamics and can easily be erased or filtered by powers that want to protect their status quo. Yet, online activism enable people to contact others, conveying information over distances and bridging gaps between people and messages, enabling individuals to join together in groups and creating new opportunities for organization (O’Donnell & Sweetman, 2018).

Given that technology mirrors realities in society, with the power to exacerbate or enhance, the issues discussed proves that those topics need to be discussed to realise the full potential of the digital revolution for social change. With all their sticks and bullets, the government and other powers can greatly impact the voice that wants to be heard in real life as well as online. But in one way or another, people will fight for what they stand for, and it is undeniable that social media has been playing a big role in bringing messages into the world.

Concluding personal reflections

This module including the assignments and creating the blog taught me many lessons and after writing this final blog, I realised how much I have learned regarding new media and activism. First of all, I would like to point out the topic that we chose as a group: feminism through new media. In light of this, we paid attention to the events that are happening in Iran but we also looked back at similar events happened in the past. One of those were the events that happened during the Egyptian revolution, with many including women’s involvement. One of them was the girl who attended the protests and was beaten by the police. The Egyptian revolution, and in particular this event, was though to talk about since I experienced it myself almost 11 years ago.

Another point that I would like to stress is that I learned a lot about the writing style that was required in the assignments. With writing a blog, you do need reliable resources to back up your article and opinion, yet an academic writing style does not fit the character of a blog. By making the blog interesting for everyone, I learned storytelling in light of an academic environment.

Following this, writing a blog also required engaging the readers, rather than just providing high quality content and information. It requires a personal touch, a look inside the author’s brain, an understanding of where the author comes from. Yet, writing a blog and sharing your opinion also comes with the responsibility of how your opinion can be interpreted and what is fair. This also is a very different perspective on using information, out of an academic writing style.

Last but not least, I learned many advantages of the use of social media and the benefits of being digitally connected. However, by looking more close at events that involved the support of social media, I discovered that there are many factors that still need to be discussed (such as online inequalities and the misusage of big companies and governments). Social media is fed by the public but it is not owned by them.

References

Bushwick, S. (2022, 13 oktober). How Iran Is Using the Protests to Block More Open Internet Access. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/how-iran-is-using-the-protests-to-block-more-open-internet-access/

Heeks, R. 2017: Information and Communication Technology for Development (ICT4D)Links to an external site.. Abingdon: Routledge.

Mutsvairo, B., Bebawi, S., Borges-Rey, E. 2019: Data Journalism in the Global SouthDownload Data Journalism in the Global South, Cham: Palgrave.

O’Donnell & Sweetman, C. (2018). Introduction: Gender, development and ICTs. Gender & Development, 26(2), 217–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2018.1489952

Tufekci, Z. 2017: Twitter and Tear Gas-The Power and Fragility of Networked ProtestDownload Twitter and Tear Gas-The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.