As a public health professional, I have always been a firm believer and supporter of data driven interventions. This prevents us from spending limited resources on reaching the wrong people. What do I mean by this? Take COVID-19 vaccines for example, if there is a specific community that is actively and enthusiastically coming forward to get vaccinated, why would you spend limited resources promoting the vaccine among this group? Wouldn’t it make more sense to focus our energy on a particular group with low vaccination rates? But how do we know who these people are and how to reach them? Data.

In public health programming, the fundamental principle involves looking out for the greater good. Simply put, how do you save the most lives while optimizing limited resources? When this is your focus, digital surveillance technology is an epidemiologist’s dream. What better way to track contacts of people that are infected with COVID-19 than contact tracing apps? This not only ensures that they are notified quickly, but it is also an opportunity to provide critical information about testing, treatment, isolation to prevent them from infecting others and ultimately prevent further spread of the virus.

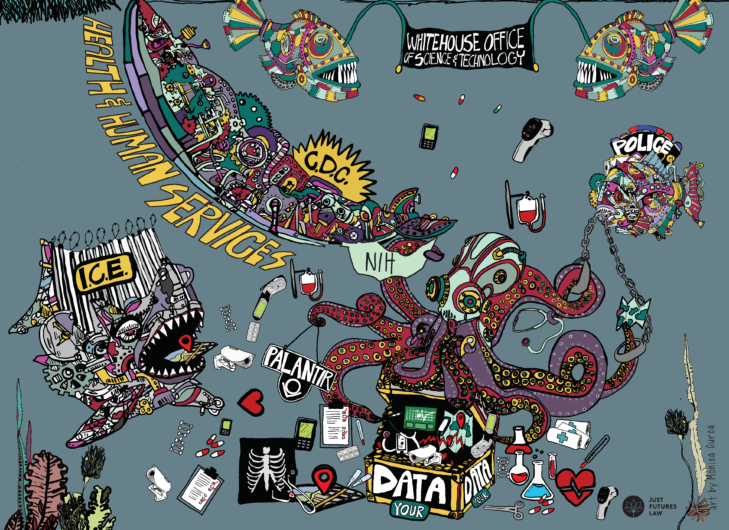

But after listening to the TED Talk “The shift we need to stop mass surveillance” by Albert Fox Cahn, a lawyer, technologist and anti-surveillance activist, I was forced to question the altruistic notion that contact tracing apps were developed for the sole purpose of keeping people safe. Albert Fox Cahn talks about contact tracing apps during the height of COVID in New York City and the fear that the police or ICE (US Immigration and Customs Enforcement) might misuse data from these apps to monitor people’s movements. Albert himself worked with the New York Civil Liberties Union, doctors, and grassroots organizations to advocate for legal firewalls which prevented the police from accessing contact tracing data. Despite this achievement, Cahn points out that the fear of being arrested from government access to public health data continues to be relevant in 49 other States in the US. This got me thinking however about all the other countries where contact tracing data may be even less regulated, allowing governments to misuse surveillance data for purposes beyond protecting people’s health. In my fellow blogger, Sara F’s post, “Responsible AI” – Who’s in the Driver’s Seat?, she raises similar questions in terms of the use of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the conflict between those that want to do good and the potential of using the same data for power and control.

And this is not unique to public health data. I also learned from Albert’s TedTalk that governments can actually buy the data that advertisers collect both online and offline. If the government in Louisiana wants to monitor who is entering an abortion clinic for example, they can buy this data. And if the government can’t buy it, they can get it through something called a “geofence warrant” which forces companies to hand over location data of every single person within a specified geographical area! Geofence warrants have led to several false arrests and accusations because someone has been found at or nearby the scene of a crime by chance.

This got me thinking about all the chatter around data privacy and the long, wordy policies that corporate websites develop and display before you can enter their site. Who has time to read these? Personally, I click accept and move on without really thinking of the implications. I’ve also downloaded COVID-19 contact tracing apps in many of the countries that I visited over the last 2 plus years – because I believed they were there for my own protection – and the protection of others. The greater good– as we call it in Public Health.

But before entering a site or logging onto an App, does the long winded, wordy policy that nobody reads say anything about the fact that the government has the right to access your personal and location data? That with a geofence warrant, you can lose your anonymity in an instant and are subject to being traced and tracked? If I were an undocumented mother for example, and at risk of being deported and separated from my children if discovered by ICE, would I think twice before downloading a contact tracing App? In all honesty, I’m pretty sure I wouldn’t even consider it at all. In this case then, are we still looking out for the greater good, or are we ok with some people being excluded? Even if these are the very people who may be the most at risk, like potentially undocumented essential workers in service industry roles, with limited access to health care?

Albert Fox Cahn ends his podcast by leaving viewers with a glimmer of hope. He says that it is possible for state and local governments to enact bills which act as legal firewalls, like they did in New York, to protect citizens from a lack of transparency around the use of data. And many countries have already done this. But there are also many other countries where this is not the case, where governments may not feel that it is in their best interests to protect personal data, and the people don’t really have much of a say, regardless of how they may feel about it. This makes me want to do some more digging, to better understand how this issue is being addressed in the “global south” where the potential for human rights violations, in some cases, can be much higher.

Stay tuned for my next blog to hear more about this as I explore the implications of digital COVID-19 contact tracing across the globe.

In the meantime, if you want to view this TedTalk in its entirety, check it out here.