Social media use during general elections in a politically polarized state.

In 2025, Guyana, one of the world’s fastest-growing economies, projected to grow by 47% in 2022, will have general elections (Wyss, 2022). It does not take elections, whether local or general, for the country’s political parties to mobilize support or maintain supporter engagement. It happens daily in some form or the other.

Offline: Politics and Ethnic Violence

To be a Guyanese is to know of or experience some form of politically motivated ethnic conflict. Even if political alignment is not the intention, ethnic conflict continues to return to political discourse, with politicians and citizens fanning the flames of a pot whose water is already dangerously hot. Although the call for national unity is increasing, led by the nation’s current president Dr Irfaan Ali, it is not without a battle of sorts.

Guyana is an ethnically polarized society, and the world is aware of it. Polarization has affected not only elections but national development, and it was not always the case. Guyanese fought together against social injustices and colonialism until the rise of several ethnically motivated wars post-1953 (Westmaas, 2022).

In 1953, Britain, Guyana’s last colonizer, suspended the Guyana constitution and installed an interim administration after a general election won by the People’s Progressive Party Civic (PPP/C), led by Dr Cheddi Jagan was not to its liking. In the elections held in August 1961 under a new Constitution, the PPP gained the majority vote again. However, by then, the PPP had split with former member Forbes Burner forming the People’s National Congress (PNC) (BBC, 2019; Caribbean Elections, 2022).

The PNC became Guyana’s first post-independence government with speculated support from the US and Britain. They held power from 1964 to 1992, with the PPP taking over after winning the 1992 elections. Twenty-three (23) years later, in 2015, the PPP lost to the PNC, which rebranded as A Partnership for National Unity (APNU). APNU joined forces with the Alliance for Change (AFC), and the two parties became Guyana’s first multiracial coalition government.

Although there are cross-overs of black and Indian supporters in each party, the PPP maintains a large East Indian following, while supporters of APNU are predominantly of African origin.

Despite attempts at promoting peace and dialogue in the past to develop a more inclusive state, election demonstrations led to violence and civil disturbances between the two main parties and their predominant supporters (Caribbean Elections, 2022). Civil unrest never ends at elections, either. Race-baiting and actions that incite racial tension, sometimes through independent media, occur, resulting in protests and death (Trotz, 2012; BBC, 2019; Chabrol, 2022; Bhagirat, 2022; Kissoon, 2022; GSA News, 2022). Politics and race become the focal point of these incidents. During the 2020 elections and post-it, history repeated itself.

The 2020 Elections and Social Media

The power of social media was harnessed in the 2020 elections, more so by the PPP, to rally citizens, which led to their victory, to call for free and fair elections and to encourage an end to the political standoff.

Although the PPP won the March 2020 elections and the motion of No-Confidence in 2018, APNU/AFC did not leave office until August that year. Events leading up to the elections and post-elections make this unique. The PPP had conceded when they lost in 2015, not without protest but without extreme, if any, physical conflict. For Indo-Guyanese APNU’s refusal to hand over power was a bitter reminder of the past. Supporters used social media to express their frustration, including the diaspora.

Reflecting on the 2011 nascent uprisings by Tufekci (2017:11) reminds me of how I view the 2020 elections and the impact of social media. Tufekci (2017) says that it was the witnessing of ‘long-standing trends in culture, politics, and civics in many protest movements that converged with more recent technological affordances—the actions a given technology facilitates or makes possible’.

Supporters were not content with speaking behind closed doors, protesting or being passive-aggressive in public. There was a strong need to make it known to the world and to rally support from the Global community Citizens banded together online, calling on (and tagging) foreign governments, international bodies and the diaspora to remove the coalition from political office and safeguard democracy and racial equality #GuyanaElections2020 on Twitter trended within the region between March and August of that year.

Big turn out in Toronto, Canada against vote rigging in the #guyanaelections2020 🇬🇾

Big credit to the organizers for the welcoming atmosphere and 0 tolerance for racism✊🏽 and for mentioning #InternationalWomensDay and the roll of Guyanese women in struggles past and current. pic.twitter.com/7pcBDj8QHk

— KevBriLall 🇨🇦🇬🇾 (@KevBriLall) March 9, 2020

Thank you! Thank you Thank you Democracy prevail!!! #guyanaelections2020 @OAS_official @SecPompeo @WHAAsstSecty @WHNSC @RepSires @CaribbeanCourt @UN @LilianCGAC @EsperDoD @antonioguterres @DeptofDefense @DRL_AS @MGrant_Canada @CARICOMorg @CarterGuyanaEOM @CaribbeanCourt pic.twitter.com/fleOQqyMNr

— Samantha Samuels🇺🇸 (@Samanth61172685) August 2, 2020

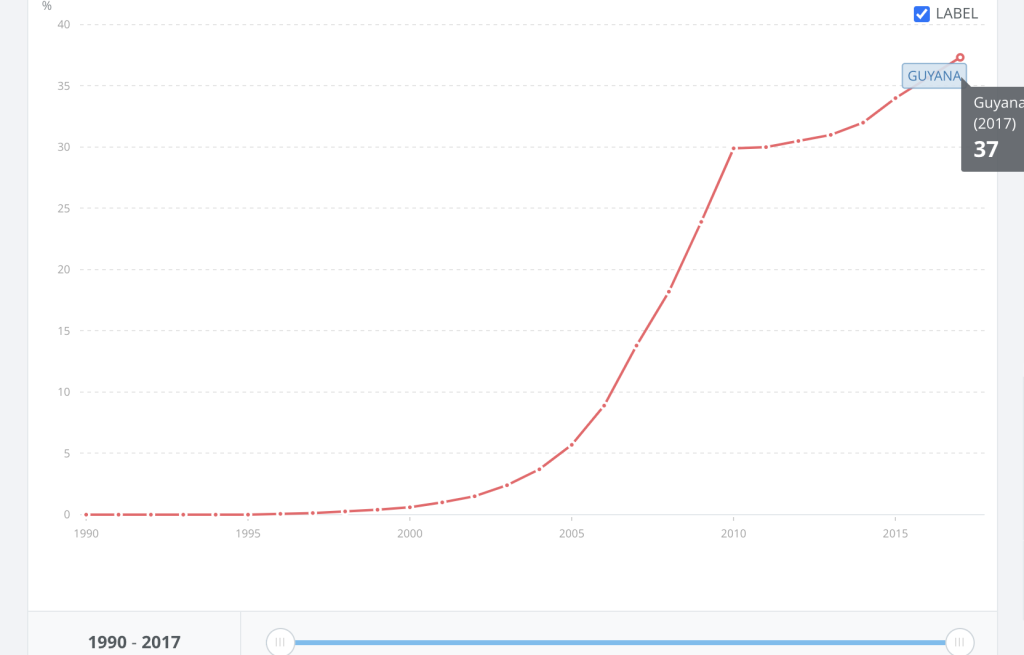

More Guyanese had access to the internet than in previous years, so the internet was awash with election content. Usage grows each year steadily.

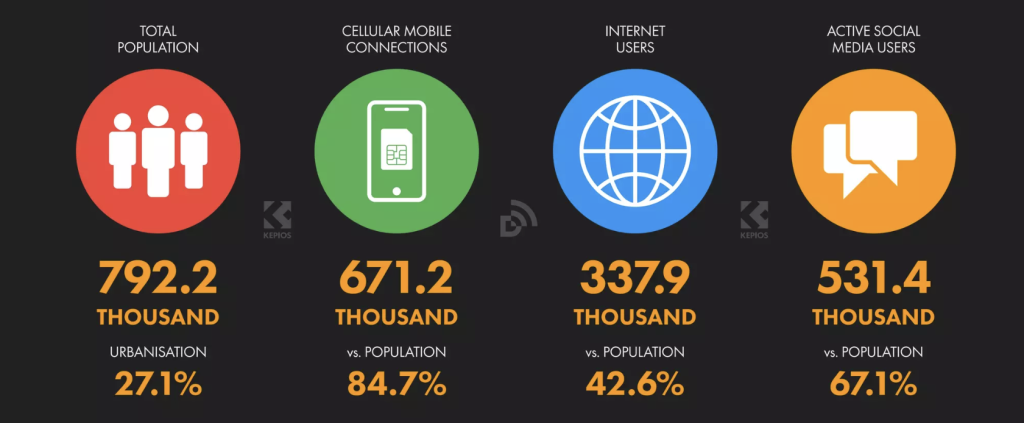

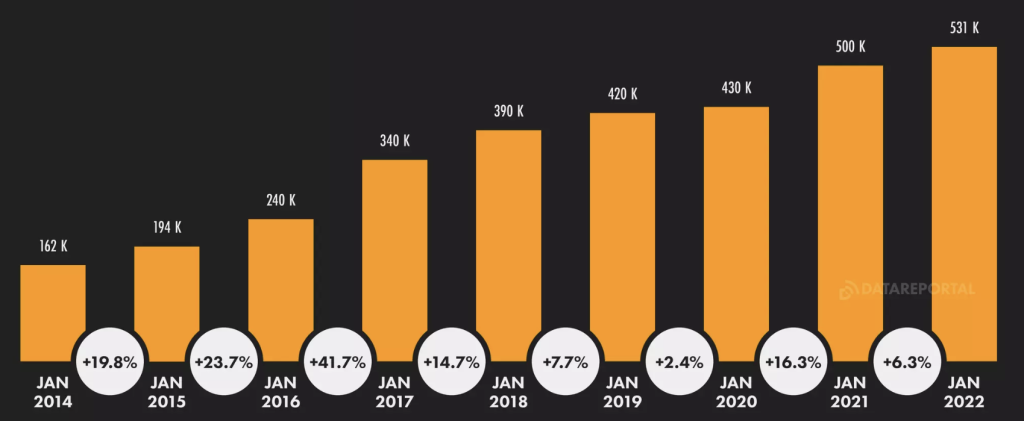

The Digital 2022 report showed that as of February 2022, there were approximately 531.4 thousand users out of a population of approximately 792.2 Guyanese persons (Kemp, 2022). Although noting that social media users may not represent unique individuals, 531.4 thousand users are 67.1% of the population, a 6.3 per cent increase from 2021 (Kemp, 2022).

There was a 16.3 per cent increase in social media use between 2020 and 2021 (Kepios, 2022). It is noteworthy that the last increase happened in 2015 during the previous elections.

The PPP and, to some extent, APNU have bolstered their online presence by investing significantly in resources needed to expand their influence since 2020.

The carefully curated and frequent social media content by the PPP is not new to the party. However, there is an increase in digital media content. With Guyana’s newfound oil wealth, the political stakes are high. Whoever leads the nation controls its wealth and development, and everyone is watching.

Despite a more expansive digital divide in the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) region in the early 2000s, Bonilla and Cliché (2001) said there was a need to promote alliances among civil society organizations, academia, the private sector, and governments to build an information society centred on communication freedom, citizen participation and collective access to knowledge A horizontal approach to communication through the internet would improve the level of political participation and make local governance and social policies more transparent (Bonilla & Cliché, 2001).

Transparency builds trust.

Therefore, the PPP sees the value of technology for infrastructure growth and a strong presence in digital spaces. The more people access the internet, the more likely they are to be on social media and access and engage with political content.

This year, approximately $1.3 billion Guyana dollars has been allocated for the development of the country’s Information, Communication and Technology (ICT) sector, which will see more ICT hubs, improved public WIFI and the 115km expansion of the government fibre optic cable network to deliver additional services to several remote communities (Garnet, 2022).

Social media: A double-edged Sword

During elections, parties developed communication and media strategies with online campaigns to boost voter turnout and market their national plans. Propaganda is sometimes a part of these strategies. However, supporters and not parties themselves often set the flame to avoid being viewed as inciters of hate that can fuel violence, especially ethnic violence.

Political parties and their supporters locally and within the diaspora spend millions of dollars and copious amounts of time using some of those resources to jumpstart social media campaigns.

Sometimes, however, things turn ugly. Between a flurry of racially motivated comments and strong politically opinionated posts, occasionally not grounded in fact or reality, the dark side of general elections has revealed itself online.

It is almost like “Mo Fyah, Slow Fyah”, a term coined by the late Desmond Hoyte, former opposition leader, which is purported to have meant that his party supporters should destroy infrastructure and create national mayhem, has slithered its way into the social media, with the intent of destroying peace among the Guyanese. Social media has created a digital battlefield where political supporters, activists and even private media can create chaos that often spills into the real world.

Austin Jr. (2019) sums up the dangerous reality of social media in the elections using Exxon’s discovery as the catalyst of change within the political system, citing a negative consequence being that social media, a key communication mechanism for reaching the masses, will be utilized by incumbent governments to saturate this space by arguing their case. At the same time, those outside of power can spread disinformation and create disruption (Austin Jr., 2019).

However, technological changes allow for altering societal architectures of visibility, communication and the public sphere, which is digitally networked and includes mass media. This altering affects social norms and political structures, often benefitting political challengers who can oppose ‘crumbling, stifling regimes’ trying to control the public discourse, in turn, overcoming censorship, coordinate protesting and organising logistics with ease, to name a few that would have seemed ‘miraculous to earlier generations’ (Tufekci, 2017).

Reflecting: Digital Development in the Caribbean

In the last few weeks, I have attempted to explore ICT4D in the Caribbean, a region of many developing nations. Although my blogs were a mere scratch on the surface of topics that demands more writing and research, it was interesting to explore the growth of digital development within the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), which includes my country, Guyana. Moreover, the policies in digital spaces ultimately impact the region’s development communication, human rights and socio-economic advancement in the future.

Entering the blogosphere with commentary on the digital divide set the basis for understanding how internet access has affected CARICOM Generation Z and Millennials, especially those working to promote development initiatives within INGOs. INGOs depend on the expertise of their professionals to use technological innovation to meet their commitments and fulfil several mandates. ICT4D is essential for promoting development initiatives and helps these organizations provide much-needed humanitarian assistance, garner donor and partner support and contribute to socio-economic growth by providing resources. Whether or not stationed in a developing country, INGOs rely on interns and staff, mainly from these two generations, to know about ‘all things internet and tech’ Although they recognize the disparities in development communication approaches between country offices in developed and developing regions, missions sometimes appear oblivious to these facts internally This post questioned the widely accepted term used to describe those born in the new technology era when applied to CARICOM youth and, more so, how this affects the work of INGOs.\

However, as hopeful as one can remain that the digital divide will soon be narrowed, several changes within the tech sphere, especially on digital platforms, have and will impact developing countries as they enter a new digital transformation era. Whether or not the region has begun seriously considering these issues remain to be seen. However, with the increasing use of online platforms by CARICOM Governments, activists and the population, policy changes will ultimately impact social media for development. Elon Musk’s content moderation council is a new example of the complexities that can arise for countries with weak human rights laws.

Sources:

Austin Jr., R. (2019, May 19) Beware Guyana: Social Media – The Political Double-Edged Sword Guyana Chronicle Retrieved from https://guyanachronicle.com/2019/05/19/beware-guyana-social-media-the-political-double-edged-sword/.

BBC (2019, February 11) Guyana profile – Timeline Retrieved from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-19546913.

Bhagirat, L. (2022, June 29). Mon Repos vendors beaten, looted during Quindon Bacchus protest Stabroek News Retrieved from https://www.stabroeknews.com/2022/06/29/news/guyana/mon-repos-vendors-beaten-looted-during-quindon-bacchus-protest/.

Bonilla, M. & Cliché, G. (Eds.) (2001). Internet and Society in Latin America and the Caribbean Malaysia: Southbound Retrieved from https://prd-idrc.azureedge.net/sites/default/files/openebooks/017-9/index.html#page_3.

Caribbean Elections (2022, November 07) Brief Political History and Dynamics of Guyana Retrieved from http://www.caribbeanelections.com/gy/education/history.asp.

Garnett, T. (2022, January 27) $1.3B budgeted for national ICT development Guyana Chronicle Retrieved from https://guyanachronicle.com/2022/01/27/1-3b-budgeted-for-national-ict-development/.

GSA News (2022, June 29). Yesterday’s Riots and Looting Had Little to do with Quindon Bacchus Retrieved from https://guyanasouthamerica.gy/news/2022/06/29/yesterdays-riots-and-looting-had-little-to-do-with-quindon-bacchus/.

International Telecommunication Union ( ITU ) World Telecommunication/ICT Indicators Database (2017) Individuals using the Internet (% of population) World Bank Retrieved from https://data.worldbank.org/country/guyana?view=chart.

Kemp, S. (2022) Digital 2022: Guyana Data Portal Retrieved from https://datareportal.com/reports/digital-2022-guyana.

Kepios (2022) Digital 2022: The Essential Guide to the Latest Connected Behaviours Retrieved from https://www.slideshare.net/DataReportal/digital-2022-guyana-february-2022-v01.

Kissoon, F. (2022, June 30) Indian lives matter: Cotton Tree 2020, Mon Repos 2022 Kaieteur News Retrieved from https://www.kaieteurnewsonline.com/2022/06/30/indian-lives-matter-cotton-tree-2020-mon-repos-2022/.

Trotz, A. (2012, July 30). International Solidarity with Linden Stabroek News Retrieved from https://www.stabroeknews.com/2012/07/30/features/in-the-diaspora/international-solidarity-with-linden/

Tufekci, Z. (2017) The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest New Haven & London: Yale University Press Retrieved from https://mau.instructure.com/files/1706707/download?download_frd=1.

Westmaas, N. (2022, January 23) From Emancipation to Independence: An outline of riots and disturbances in Guyana Stabroek News Retrieved from https://www.stabroeknews.com/2022/01/23/sunday/from-emancipation-to-independence-an-outline-of-riots-and-disturbances-in-guyana/.

Wyss, J. (2022, July 25) World’s Fastest-Growing Economy Seeks to Diversify Away From Oil Bloomberg Retrieved from https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2022-07-25/world-s-fastest-growing-economy-seeks-to-diversify-away-from-oil.

Photo by Hyotographics (Shutterstock).