According to the media, techno-optimism is everywhere. There’s a lot of buzz around the metaverse, artificial intelligence, web 3, NFTs… the list goes on. But what do these terms actually mean, and what good (or bad) will they deliver for society?

I had the chance to delve deeper into this question by attending a panel discussion at the Partos Innovation Festival in Amsterdam on 14 October called ‘Digital Futures: is technology making or breaking social justice?’

The future of tech

First, the panel clarified some misunderstandings. The metaverse isn’t just Facebook. NFTs aren’t just the Bored Ape. Blockchain technology (briefly defined in my previous blog post) is more than crypto. So what are they?

I learned that the metaverse is a range of virtual ‘worlds’ where life can play out online. As far as I can tell, it’s like popular computer game the Sims, but there are real people behind the avatars and there’s real money behind the Simeons. In the metaverse, for example, we could use virtual reality to provide immersive education and training to teachers, students and healthcare workers.

NFTs, or non-fungible tokens, represent a new kind of digital ownership based in blockchain technology. Art is far from the only potential of the technology. In the future we might have our passports or graduation certificates as NFTs, making them more secure and harder to fake or steal.

Staying in the realm of blockchains, Web3 will be a blockchain-based internet, where ownership of online spaces is taken back from big tech companies and returned to internet users. Rather than being the data or the product, we might become the owners.

Sounds pretty exciting, right? But we need to dig deeper into some of the assumptions underlying this shiny new future.

Seize the means of production

Panellist Dr. Peaks Krafft made a compelling case for techno-pessimism. They pointed out that ownership is important, but ownership of content isn’t the only aspect. What about who owns the infrastructure? Even in a changing tech landscape, it’s still a few small players who own the vast majority of the infrastructure. Think of Amazon’s vast web hosting services, which are the most profitable part of its (massive) business.

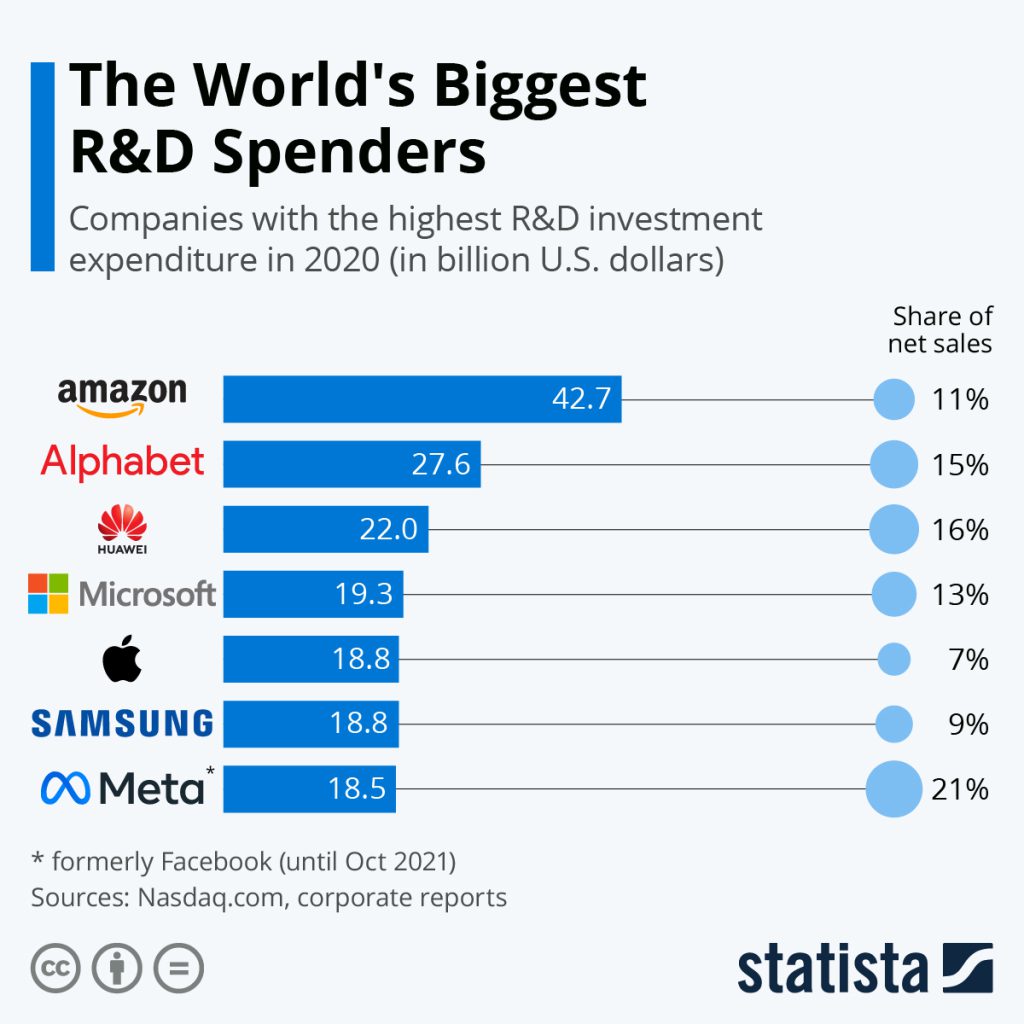

We also need to look at the investment that funds new technologies. Spoiler alert: it’s big tech. The biggest players in tech will be the ones investing in new technologies that are ostensibly for the people, such as Web3 or metaverses. And they will stay the biggest players. We are a long way from a democratic, decentralised system of technology access.

Source: Statista 2022

Digital spaces are also spaces of exclusion

If you’re a reader of this blog, you already know that technology isn’t neutral. Many decisions that affect people’s lives, from deciding whether they are credit-worthy to deciding visa status, are increasingly based on algorithms.

We can’t forget that algorithms are programmed by people, who bring their own (conscious or unconscious) biases into decision-making that replicate systems of exclusion, oppression, and discrimination. Just look at the ‘robodebt’ scandal in Australia, where recipients of government benefits were falsely accused of owing money to the government. Similarly in the Netherlands, an algorithm falsely accused tens of thousands of parents and children from mostly low-income and ethnic minority families receiving child benefits of fraud – ruining lives in the process. The panel discussion highlighted that the more we rely on tech for these bureaucratic decisions, the more we end up with a technocratic form of government without any flexibility.

Further, we can’t forget that access to technology is not equal. According to the World Bank, in 2018 approximately 1 billion people had no official proof of identity. Almost 38% of the world’s population in 2022 did not have access to the internet. If our future involves moving even more of our daily lives into online and virtual spaces, then we are excluding a great deal of humanity, and exacerbating the existing inequalities separating the richest from the poorest.

The elephant in the room

What about the impact of all this new technology on the environment, in this time of climate crisis?

We know that Bitcoin mining has enormous environmental impacts. But what about the underlying blockchain technology – the basis for Web3, the ‘future of the internet’, and NFTs? At this point, it’s surprisingly difficult to quantify the environmental impact of blockchain technology more broadly. Etherium, a major player in the cryptocurrency and blockchain space, has acknowledged the environmental risks of blockchain by launching an update that will make its products ‘greener’. But experience with cryptocurrency so far should encourage caution.

We should all be techno-pessimists

One word that wasn’t mentioned in the panel was ‘capitalism’. Beyond communication, at present most applications of new technology are for gaming, entertainment, investment and wealth creation, and shopping – mostly supported by online advertising. In a capitalist society, everything needs to be monetised, and new tech is no exception. It’s difficult to see how ‘even more ads’ offers a more connected, productive and enjoyable future for human beings.

That is, of course, a value judgement. Certainly digital transformation brings great benefits in terms of efficiency, information sharing and communication across geographies. One panellist advocated educating developers on the risks of bias in designing algorithms. This seems like a great place to start.

But ultimately I was most swayed by the persuasive arguments of Dr. Krafft. If we let ourselves get carried away by the potential of new technology without stopping to ask how this will impact different groups in society, we could do more harm than good. If the goal is social justice, ‘technology for technology’s sake’ is not a good enough argument. Sometimes, pessimism is a constructive thing.