This article is an elaboration of the post I published on our blog on 21 October 2023: “Solutions journalism and digital humanitarianism: Two distinct yet related concepts addressing social issues.” In this article, I will attempt to link the arguments made on the blog with academic debates and existing literature.

Definitions of solution journalism and digital humanitarianism

Solutions journalism is a storytelling approach that, as the US-based Solutions Journalism Network defines it, focuses on programs related to the response of solving social problems on local, national, and international levels. In simple terms, it is storytelling about how people are trying to solve problems and what the rest of the world can learn from their successes and failures. Many news organizations are currently redefining how they tell stories, and one tool they are utilizing to reconnect with members of their communities is solutions journalism (Usery, 2022). Solutions journalism also carries with it the inherent premise of improving audiences’ sense of trust in journalism and enhancing civic engagement through reporting on evidence-based progress to generate realistic hope that even the most persistent social problems are not intractable (Nelson and Dahmen, 2023).

Digital humanitarianism presents new technological approaches to ameliorate humanitarian work (Shringarpure, 2020). It can be tricky to conceptualize since it is decentralized, self-organized, volunteer-based and virtual (Phillips, 2015). As Norris describes in her article, digital humanitarianism is “not tangible in the traditional sense of collaborative working groups, and it is also a relatively new inter-disciplinary field which integrates social computing and technology, information systems, networked collaborative organizational structures, communication and emergency management” (Norris, 2017). There is no one discipline, theoretical home or practice upon which to lay down a marker, which also complicates its definition (Ibid.). There is no doubt that technology is a crucial part of digital humanitarianism. In fact, Cyber-intelligence, security and development apparatuses, and social media realms are constituents of a vast technological nexus, and the term ‘digital humanitarianism’ can encompass those concepts and much more (Shringarpure, 2020). In this article, we shall focus on digital humanitarianism within the context of voluntary citizen journalism and crisis news reporting.

How are they related?

Solutions journalism and digital humanitarianism share a common goal of addressing social issues and promoting positive change in the society. The solutions-oriented approach to storytelling includes voices who have the tools to combat local, national, and international problems as well as those who have been directly impacted by issues. This back-and-forth narrative gives deeper insight into issues pervading society (and what can be done about them) than a traditional news story might (Usery, 2022). Moreover, insights mined from semi-structured interviews often indicate that the practice of solutions journalism is evolving, and that symbiotic relationships formed through its practice can aid in building credibility, creating stronger bonds within communities, and positively impacting underrepresented communities through tangible change (Ibid.). Similarly, digital humanitarianism is perceived as a potential solution to the technical and communication barriers faced by emergency managers (Hughes and Tapia 2015). By use of online collaboration tools such as social media hashtags, digital humanitarians often play a critical role in ensuring information reaches the public and decision makers in a timely manner, increasing chances for action to be taken.

They both leverage the use of digital technology, which is an integral part of humanitarian responses as it facilitates access to critical support in times of crises. Networks of virtual volunteers, for example, often act as digital humanitarians who rapidly assemble situational awareness at the onset of natural and human-caused disasters through crowdsourcing, data analysis and crisis mapping to aid on-the-ground emergency response (Norris, 2017, pg213). These self-organized, online networks of information technology volunteers use human- and machine-computing methods to rapidly collect, verify and analyze data at the onset of natural- and human-caused disasters (Ibid). Likewise, as we see in the Solutions Journalism story tracker, a vast majority of solution-based media organizations are also online. These journalists use modern technologies not only for dissemination of information (through their media websites and social media), but also for research and data analysis in their response to social problems.

Both solutions journalism and digital humanitarianism often involve engaging with communities, experts, and organizations. It is quite common for digital humanitarianism to work with local communities and volunteers. Today, there are 30 Digital Humanitarian Network member organizations that are typically comprised of citizen volunteers. These groups coalesce into four primary categories of volunteers and technical communities (Norris 2017 pg215). These categories include Crowdsourcing, expert communities, volunteer recruitment, and technical infrastructure (Ibid.). Solutions journalism, being insight- and evidence-based, often involves interviewing of experts and community members to provide data or qualitative results that indicate effectiveness (or lack thereof). Journalists may also structure their stories as puzzles to be solved or mysteries to be uncovered. For example, a story about a conflict that erupted between two communities in northern Kenya would focus on probing what happened and why and how it happened, as well as how the communities in northern Kenya are coping with the conflict. The story would also explore avenues available to ensure that it never happens again. To qualify as solutions journalism, the story not only involves the communities and authorities in that region in collecting information, it also empowers the reader to engage in community dialogues and do more than think about problems (Lough and McIntyre, 2019).

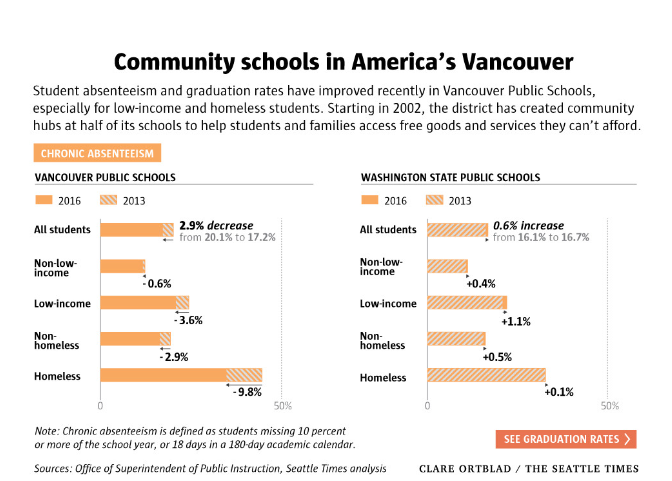

The fact that solutions journalism is evidence-based also means that data collection and analysis play a critical role. It is important for the scale of the problem being described to be demonstrable, and the response to that problem measurable. When the impact of a response can be measured with numbers, data are a good path to that. For instance, it is not enough for a climate change specialist to claim a working response on drought or unending floods without showing evidence. In 2018, for example, The Seattle Times, which runs a solutions journalism-based project called Education Lab, published a story that explained the progresses in America’s Vancouver despite soaring student poverty and demonstrated their effectiveness using data from both the local school district and the state, gaining the attention of other cities in the United States. It went ahead to perform its own analysis to verify the results as shown below:

Like solutions journalism, digital humanitarianism is often evidence-driven and uses a lot of data in their reporting. As Aitamurto (2015) explains, “The standards and practices of data collection, verification and sensemaking in information management have analogs in journalism routines that offer interesting opportunities to expand the concept of crowdsourced citizen journalism as interpretive, evidence-driven and knowledge-search methods (Aitamurto 2015).” Norris (2017) shares an example of the “Standby Task Force” (SBTF), an informal volunteer network established in 2010 following the earthquake in Haiti. SBTF uses a formal activation request system which outlines its mission-compliant criteria: “humanitarian emergency declared under the International Charter on Space and Major Disasters; clear and pressing need for crisis mapping and/or situational awareness; detailed plan for data collection, sharing and privacy controls; demonstration of security risk analysis for local population and SBTF volunteers.” SBTF also offers a comprehensive online training program to all volunteer digital humanitarians on data verification standards, media monitoring practices and ethical information management (Ibid.).

One of the major differences between solutions journalism and digital humanitarianism is that the former covers a broader range of topics and is not limited to immediate crises. It looks at effective responses and solutions to various social issues over time. As I peruse through the Solution Journalism Network’s database of over 15,600 stories from across the world, it is quite clear, with each story, that there is a longer-term focus with no sense of emergency. Digital humanitarianism on the other hand is more time-sensitive and is primarily activated in response to immediate crises or emergencies, such as natural disasters, conflicts, or humanitarian emergencies. It is perceived as a potential solution to the technical and communication barriers faced by emergency managers (Hughes and Tapia 2015). Since the mid-2000s, as the rapid increase in techno-scientific journal articles attests, all manner and scale of emergencies – floods, storms, forest fires, earthquakes, power outages, traffic gridlock, even high school shootings – have been rediscovered cybernetically, by hyper-bunkered digital humanitarians, as socially distributed information systems (Bushcer & Michael, 2014). Digital humanitarianism requires rapid response and real-time information sharing during crises. Timeliness is crucial for effective humanitarian efforts.

The two also differ in their target audiences. Since solutions journalism mainly focuses on inspiring change, its target audience is typically the general public, policymakers, and stakeholders interested in understanding potential solutions to societal problems. This is evident in most of solution-based media outlets’ websites such as Apolitical, Positive News, YES! Magazine, Christian Science Monitor among others. On the other hand, since digital humanitarianism mainly focuses on immediate emergency responses, its target audience includes affected communities, humanitarian organizations, governments, and responders involved in those emergency situations.

Finally, when considering the distinct attributes of solutions journalism and digital humanitarianism, it becomes evident that solutions journalism possesses a capacity for enduring impact that surpasses that of digital humanitarianism. This is attributed to their inherent disparities in time sensitivity and target demographics. Solutions journalism, through its in-depth reporting and thoughtful analysis, wields the potential to shape not only public opinion but also policy formulation and societal transformation. These shifts in perception and systemic change, however, are processes that need time to manifest fully. In contrast, digital humanitarianism operates within the realm of immediacy, responding swiftly to pressing crises and urgent demands. Its primary focus lies in swiftly attending to short-term emergencies, such as the provision of immediate relief and the preservation of lives in the face of acute challenges. While the impact of digital humanitarianism is palpable and invaluable in the immediate aftermath of crises, its influence tends to be more time-bound.

Final reflections

From this analysis, we can see that both digital humanitarianism and solutions journalism share a common goal of positive social impact. But they differ in terms of their immediate focus, and methods of engagement. They also use technology differently. They can however, as we have seen, complement each other in addressing social issues and promoting positive outcomes.

In a world full of social problems like conflicts, diseases, poverty, droughts and floods, solutions journalism offers a breath of fresh air. While it is important for us to remain informed about all the negative events happening in different parts of the world, the excessive amount of negative news coverage tends to amplify anxiety. I cannot count the number of times I have, for the sake of my mental health, intentionally avoided watching the news due to negative headline fatigue.

Likewise, digital humanitarianism plays a critical role both in the humanitarian world and in journalism. While relatively unacknowledged in the journalism studies literature, digital humanitarianism has attracted an extensive body of theoretical and applied research in other disciplines, such as information science and computer science among other fields (Norris, 2017). The more digital humanitarians keep the public informed about crises in their locations, the more the world pays attention to them, and the faster the necessary help gets to those who need it.

The fact that these two concepts leverage on the use of information technology, data collection and cross-sector collaboration in creating social impact is a clear indication of their interconnectedness, despite their differences in other areas.

As a humanitarian worker with previous experience in journalism and a particular interest in solutions storytelling, researching on the interconnectedness between solutions-journalism and digital humanitarianism has been, as cliché as it may sound, eye-opening and interesting for me. Until I sat down to think and read about these two concepts, it never occurred to me that they could be as intertwined as they are. This whole exercise, from blogging with members of my group to working on this final assignment, is a plus not only to my career in the humanitarian sector, but also as a communication for development specialist. A huge thanks to my team members Lorena, Malan and Marie for a worthwhile group work experience, and to the teachers and other fellow students for all the feedback that helped us throughout our blogging journey.

****

References

- Usery, A.G. (14 Nov 2022): Solutions Journalism: How Its Evolving Definition, Practice and Perceived Impact Affects Underrepresented Communities, Journalism Practice, DOI: 10.1080/17512786.2022.2142836

- Nelson, J.L. & Dahmen, N.S. (08 May 2023): Appealing to News Audiences or News Funders? An Empirical Analysis of the Solutions Journalism Network’s Revenue Project, Journalism Practice, DOI: 10.1080/17512786.2023.2209779

- Shringarpure, B. (2020) Africa and the Digital Savior Complex, Journal of African Cultural Studies, 32:2, 178-194, DOI: 10.1080/13696815.2018.1555749

- Phillips, J. (2015). “Exploring the Citizen-driven Response to Crisis in Cyberspace, Risk and the Need for Resilience.” In Humanitarian Technology Conference (IHTC2015), 2015 IEEE Canada International, 1–6. Ottawa, ON: IEEE. doi:10.1109/IHTC.2015.7238051.

- Norris, W. (2017) Digital Humanitarians, Journalism Practice, 11:2-3, 213-228, DOI: 10.1080/17512786.2016.1228471

- Hughes, A.L., & Tapia, A.H. (2015). “Social Media in Crisis: When Professional Responders Meet Digital Volunteers.” Homeland Security & Emergency Management 12 (3): 679–706.

- https://digitalhumanitarians.com/partners/

- Lough, K., & McIntyre, K. (2019). “Visualizing the solution: An analysis of the images that accompany solutions-oriented news stories,” Journalism, 20 (4), 583-599.

- Aitamurto, T. (2015). “Crowdsourcing as a Knowledge-Search Method in Digital Journalism: Ruptured Ideals and Blended Responsibility.” Digital Journalism: 1–18. doi:10.1080/21670811.2015.1034807.

- Bushcer, M., & Michael, L. (2014). Collective intelligence in crises. In D. Miorandi, V. Maltese, M. Rovatsos, Nijholt, A., & Stewart, J. (eds.), Social collective intelligence: Combining the powers of humans and machines to build a smarter society (pp. 243–265). New York: Springer.

- Solution Journalism Network