2023 feels like a year of constant crisis. The ongoing war in Ukraine, the Turkey-Syria earthquake, floods in Libya, earthquake in Morocco, the exodus of the Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh, earthquakes in Afghanistan and most recently, the fighting in Gaza are just some of the big news stories of the current year. Stories like these used to be constrained to certain types of media (newspapers, news-magazines, TV-news programmes), that were consumed somewhat consciously. TV-Audiences would maybe watch the evening-news and a movie afterwards.

With today’s social media, this division between news and entertainment content became blurred to non-existent. News of crisis, memes, entertainment and fake news are mixed into one bottomless stream of images, demanding to be scrolled through.

Perpetual crises as a communication challenge.

If you follow a few big NGOs and media outlets on social media, news of wars and natural disasters are part of your daily media intake and by extension, also the connected fundraising appeals. Opening a social media app won’t give us any sort of specific content. It’s a mix of whatever channels we have subscribed over the years.

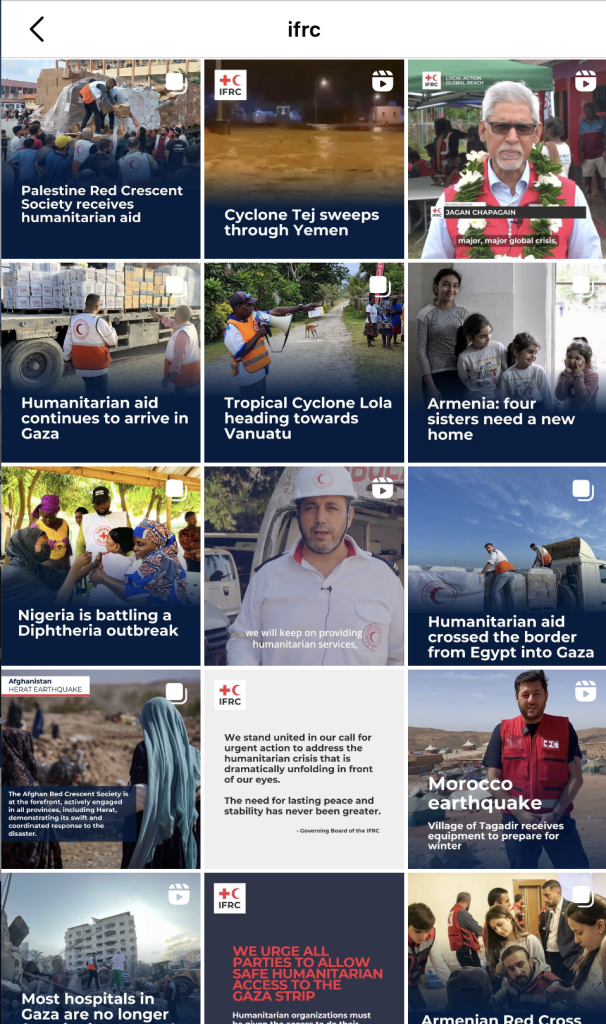

If you look at the accounts of the big international humanitarian organizations, you will see them active in many of the same crisis areas in the world. Their focus on specific issues might vary, according to their resources in that area, but big organizations can’t ignore issues, in order to not alienate their audience.

But it’s not only media outlets (who need views) and organizations (who need donations), also celebrities and regular users post about global events. VIPs might want to direct attention to a cause using their fame, while normal users can have friends and family who are affected, or they might even be affected themselves.

How can organizations navigate this modern information environment, where users might suffer compassion fatigue (a state observed in healthcare workers, sometimes applied to news audiences) ?

Image left: a the many current crises on IFRCs instagram stream at the time of writing.

How to capture the attention of oversaturated donors?

Usually, smaller organizations, who depend more on individual donations are the first to feel the impact of shrinking attention, while the bigger organizations often operate on government foreign aid money.

I could imagine a future, where NGOs have to sharpen their brands, focussing on a set of issues, or geographic regions, vs. the approach to be everywhere, all the time. This could also be approached by diversifying their communication channels, and catering specific content to specific audiences.

(Original caption: Syrian refugees receive fuel vouchers from the Lebanese Red Cross, to heat their shelters during the winter months. Registered beneficiaries show a form of ID and sign the list (with pen or fringerprint) to receive a pack of vouchers. Lebanon, 2020. Georg Wallner for the Austrian Red Cross.

Adapting to the new normal.

While the present media landscape, where your NGO content competes with ALL other content that is online is a very challenging one, it also offers many possibilities. One that is a bit surprising, is the fact that also fundraising appeals have the potential to go viral. But if that happens, you better have the capacity to back up your claims or you might end up with a shitstorm.