Whether openly acknowledged or not, neocolonialism is present in nearly all aspects of development and humanitarian work. The colonial mindset and the way it materializes in development settings impact the way we communicate about the work being done. The very fundamental power imbalances that exist between organizations and “recipients” in development and humanitarian programs also exist in the communications processes and products of these organizations.

Fortunately, development organizations around the world recognize the need for decolonization, or at least claim so. Anti-colonialism and the aim for decolonization are often among organizations’ guiding values and principles today. As they should be. Yet more often than not, the stories we tell about development work and those on the receiving end are still being told through a colonial lens, by and for an audience in the Global North, with little creative input from the recipients of aid and participants themselves.

For organizations to realize their decolonial ambitions, we must make a massive shift in the way we communicate. Allowing participants to act as equal partners in the creative process and lead the story is one crucial step among many in the long path toward decolonizing development.

Why We Need to Decolonize Development Communications

The subtle (and sometimes not-so-subtle) colonial narratives found throughout development communications are damaging for both organizations and the people they support. The too-common “helpless recipients saved by hero organization” narrative is inaccurate, belittling, and contrary to real partnership. The people depicted in these types of narratives are often misrepresented, with their agency for self-driven change reduced. Meanwhile, the organizations lose the opportunity for meaningful collaboration, which is more effective across program implementation, successful communications, and fundraising (Bond & Amref, 2022).

Yet, by focusing on partnership and participant-led storytelling, the development sector stands a chance to make a meaningful step toward decolonization. While this concept goes beyond visual communications, Jörg Arnold’s sentiment applies to the concept as a whole:

“By decolonizing visual communications, communities that have been historically oppressed, silenced, can reclaim the narratives and challenge the power structure.”

(Arnold, 2023)

Through trusted partnerships, development communications practitioners can tell more complete stories; stories that are culturally aware, which provide ample context, and representative of the individual or community’s strengths and assets. Accurate and whole representation is vital in the path toward decolonization, as “representation shapes our understanding of people and events. Indeed, representation produces culture by determining and normalizing values, ideas, attitudes, and identities” (Etem, 2020; Said, 1978; Hall, 1997).

In my previous post, I argued that ethical, representative, and complete stories are challenging to tell through digital communications channels such as Instagram reels and short captions. By collaborating with participants and ensuring their voice is central (rather than that of the author’s) we can avoid misrepresenting people and perpetuating harmful stereotypes.

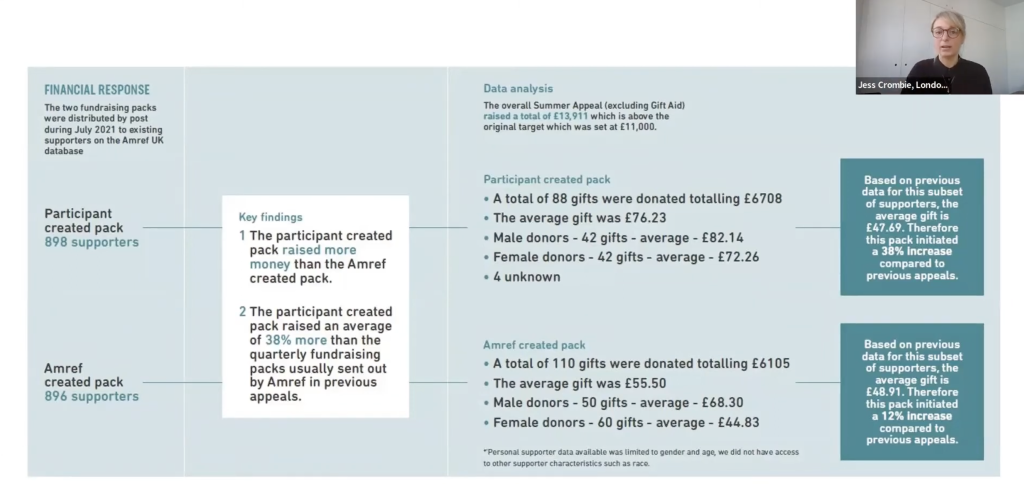

During an experiment in fundraising run by Bond and Amref, community health volunteers in Kibera, Kenya, the largest informal settlement in Africa, were asked to photograph individuals they work with, write about their stories, and create a fundraising pamphlet for the organization. Amref published one of these pamphlets and tested it against one of their own standard pamphlets. The researchers recorded quantitative financial data and qualitative emotional responses, finding that the participant-led fundraising pamphlets raised slightly more money than the traditional Amref piece. They also learned through qualitative responses that many of their UK donors greatly appreciated this narrative shift, which created a stronger emotional connection with the individuals Amref supports. One donor stated,

“It’s good to see the old paternalistic model of charitable donation give way to a realisation that Africans are capable of making their own decisions about how to help their community”

(Bond & Amref, 2022).

Another stated, “that they saw someone in control of their narrative… and making decisions on behalf of their community.”

These donor responses confirm the value and need for participant-led communications. The researchers concluded that they, “believe that this result demonstrates that when you create content that draws the donor closer not to your organization, you take a kind of a backseat in the story, but to the contributor themselves, by facilitating them to share a story of their choice in the way they choose. You help create that closeness and the result is a higher average donation” (Bond & Amref, 2022).

You can listen to the researcher’s conclusions here:

How Do We Transition to Participant-Led Communications?

In order to engage in participant-led communications, organizations must first create an environment and working arrangement to develop and maintain equitable partnerships with their participants and/or recipients, as well as local implementing partner organizations they work with. Many Global North organizations have promised “equitable partnerships” with their beneficiaries and partner organizations, but few have defined what those will look like. In order to be consistent with these relationships, we must define how the working relationship will function and the responsibilities of both sides.

Peace Direct has developed an extremely comprehensive and useful guide for developing equitable partnerships between individuals and organizations in the Global North and Global South. The numerous researchers involved in the report discovered that, “Trust, humility, respect, and mutuality/reciprocity emerged as the foundational values for ‘decolonized partnerships’, with participants highlighting their importance in building relationships and achieving meaningful outcomes” (“Transforming Partnerships in International Cooperation,” 2023, p. 5). Additionally, they discovered that respecting one another’s contributions and determining a shared vision were key behaviors for successful partnership.

It is of course worth noting that equitable and decolonized partnerships are not one and the same, as “decolonized” infers a transfer of power and agency to those in the Global South, and equity refers to maintaining an equal balance of power. Peace Direct asks whether truly equitable partnerships are possible, as the imbalance of funding will always place undue control in the hands of Global North organizations (2023). For the moment, I believe aiming toward equity is a fair and necessary first step.

The organization I work for, RefugePoint, partners with multiple community-based refugee-led organizations. One of these organizations, Youth Voices Community, trains refugees and Kenyan youth in Nairobi on media literacy, photography, and more to engage in advocacy and online campaigns. We are in the early strategy phase of determining ways to partner with Youth Voices to decolonize RefugePoint’s storytelling. Right now, we are looking into ways for Youth Voices to provide photography and video training for our refugee clients, enabling them to tell their own stories, rather than myself doing so. As Peace Direct suggests, our U.S. team acknowledges that we must “Unlearn assumptions about who holds technical expertise and what technical expertise is” (2023, p. 7) to capture the most honest and equitable stories.

In RefugePoint’s current communication system, our team in Nairobi and the U.S. would support in the creation of these stories, as well as edit, and publish them. This means that the U.S. team still makes the final editorial decisions, begging the question of whether this is truly an equitable relationship.

This leads to the next key step toward a participant-led communications strategy: organizations in the Global North and their communications and fundraising staff must relinquish control of the narrative. This can be quite difficult for communications practitioners, whose role is to act as an editor, ensure consistency, and maintain the brand voice. Inherently, participant-led communications may have a different voice, which will likely look and feel different than staff are used to.

We see the inability to do this in UNICEF’s award-winning Unfairy Tales project, where “institutional agents control which memories of Syrian refugee children are narrated and that they select the content to elicit awareness and donations” (Etem, 2020). As a video editor, this is entirely understandable at face value, since your job is to choose the most compelling quotes, often from a very long interview, to include in the video. However, when an editor selects the quotes to include, they are essentially taking the agency of being able to tell one’s own story away. In this situation, the editors left out key details that changed the audience’s perception of the children’s stories.

While certain aspects of this project were certainly unethical, Etem points out that, “The choice of preserving the children’s original voices in Arabic makes them a prominent part of the authorship. This choice also gives the film a degree of intimacy and authenticity and attempts to minimize distortion of the way the children are represented” (2020). To produce a more ethical film, the producers could have shown the film to the children before publishing, asking whether the most important parts of their stories were accurately represented. When producing films for RefugePoint, my team has sent draft videos to the participants to see whether they feel well-represented and comfortable in the manner they’re portrayed before publishing. If we had more time and resources, and if they were interested in doing so, it would be more ideal to include participants throughout the editorial process, including choosing what quotes best illustrate their story.

Both the UNICEF Unfairy Tales project and the films I have created for RefugePoint gave refugees (the participants) a voice, but ultimately it was the institutional agents who had control over how the voice was used and transformed (Etem, 2020).

Challenges in Participant-Led Communications

- Making a major shift in the way we communicate development work obviously comes with challenges. As with most challenges in our field, funding (and therefore bandwidth) may be the biggest hurdle. Many organizations operate with small communications teams, perhaps just a single individual. Engaging participants takes time, and doing so ethically and equitably takes even more. Incorporating participant-led communications strategies may seem overwhelming, if not impossible for teams struggling to keep up with their day-to-day responsibilities. However, once participant-led strategies are established, they may actually lighten communications teams’ workload in some capacities (more on this in the Solutions section below).

- Language barriers also present a manageable but formidable barrier. Assuming the program participants may speak a different language than Global North NGO staff, a translator will be necessary. It’s worth noting that translation will be required in more circumstances than one might initially think. Need to have a quick phone call to double-check a fact? A translator would need to be available to join the call. Then organizations must decide how they’ll choose to translate – word for word, 100% accurately, or for the intended meaning, so that subtitles are more easily understood by a Global North audience.

- Communicating via social media platforms and other digital channels presents another challenge for participant-led communications. As I mentioned in a previous post, the need to condense complex issues and stories into a 20-second reel is inherently problematic. These issues are rarely simple, and simplifying participant’s stories risks misrepresenting their identity. Yet communications practitioners are typically tasked with creating content for maximum impact, and “knowing what [the] algorithm wants is seen as crucial to the public reach and the impact of the messages published by humanitarian organizations online and, consequently, efforts to figure out what social media algorithms want have moved to the centre of humanitarian communication” (Ølgaard, 2022). All this is to say that participant-led content may not perfectly align with standard social media criteria or the algorithm’s needs. Regardless, this type of content has been shown to generate real conversations and emotional connections with donors and those practitioners seek to reach (Bond & Amref, 2022).

A Few Solutions

- Above, I mentioned funding and bandwidth as potential challenges in the shift toward participant-led communications. Engaging participants in communications will require an upfront investment of time and money, possibly training as well, but once this has been done, participants may just be the best photographers and storytellers available to convey organizational impact. At RefugePoint, we have paid participants for their time during interviews and comms activities. I foresee doing the same if they were on the other side of the lens.

- Regarding language barriers, finding a trusted and talented translator is key if you don’t speak the same language as the participants you’re working with. I’ve discovered that high-quality, accurate, and legible translations are quite difficult and usually require a translator with years of experience. Contracting experienced translators may be necessary for organizations seeking to decolonize their communications. In addition to contracted translators, a live-translation service like Tarjimly, which offers free, remote translation for organizations, refugees, and immigrants, can be incredibly helpful.

- For development professionals from the Global North to shift towards more decolonized communications practices, they must share editorial decisions with the people who implement the programs, as well as those on the receiving end of those programs. When examining UNICEF’s campaign, Etem found that “Collaborations like Unfairy Tales need to feature greater production control from the subjects they were made to support—in this case, from the actual refugees” (2020). If these stories will inevitably end up as short-form social media content, organizations should include participants in the decision-making on what quotes, images, etc. to feature, to most accurately and ethically represent their identity.

Conclusion

If organizations in the Global North truly respect the agency and dignity of those they serve, their communications staff must stop treating program participants as passive assets for fundraising, and instead involve participants in communicating about the work. Uplifting individuals and empowering them to determine their own narrative, rather than creating one for them, is a vital step in humanitarian and development service. This empowerment shifts both the narrative that organizations communicate, to one of transparency, equity, and partnership, and the narrative that participants tell themselves, to one of strength, capability, and resilience; thus better serving the individuals and communities.

Reflections

The past six weeks of blogging have been a valuable refresher lesson in WordPress, its numerous features, and the benefits and challenges of working with a team in different time zones with entirely different schedules. Our prompt – ICT4D, Aid Work, and Communicating Development allowed our team to pursue a wide array of topics, in which I focused on representation and ethics in relation to digital communication and of course, participant-led communications. As I lead the photography and video efforts at an international NGO supporting refugees, all of which are published digitally, the reading and research I undertook to write these pieces was incredibly relevant and valuable for my professional endeavors. As a video editor, I am guilty of making similar editorial decisions as UNICEF did in their study (though I don’t believe as unethical), and reading and considering a critique on Unfairy Stories will help shape the way I edit moving forward. Additionally, I’m often asked to develop short-form content, and forced to leave out personal details, which misrepresents the people I’ve interviewed. Hearing about other organizations’ success including participants in editorial decisions to eliminate this issue is exciting and thought-provoking. Finally, Jörg Arnold’s lecture was one of my favorites in the program so far, and I plan to reach out to learn more about Fair Picture’s model and possibly hire photographers in their network.

The ideas I worked on in the blog posts are ones that I ask myself almost daily while working, and I’ve already brought some of these concepts to our communications department. My team at RefugePoint is in the process of planning for 2024, and I’ve shared the findings from the Bond & Amref study while suggesting ways that we can engage participants more often in our communications strategies. It’s worth stating again – the relevance of this exercise to my daily work has been incredible.

References

Transforming Partnerships in International Cooperation. (2023). In https://www.peacedirect.org. Peace Direct. Retrieved October 15, 2023, from https://www.peacedirect.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/Peace-Direct-Transforming-Partnerships-Report-English.pdf

Arnold, J. (2023, October 14). Presentation fairpicture.org. Comdev – Advances HT23, Malmö, Sweden. https://mau.instructure.com/courses/15087/external_tools/150

Etem, A. J. (2020). Representations of Syrian refugees in UNICEF’s media projects: New vulnerabilities in digital humanitarian communication. Global Perspectives. https://doi.org/10.1525/gp.2020.12787

The Technopolitics of Compassion: A Postphenomenological Analysis of the Digital Mediation of Global Humanitarianism. Ølgaard, Daniel Møller (2022). [Doctoral Thesis]. Lund University. https://lucris.lub.lu.se/ws/portalfiles/portal/117665567/_LGAARD_thesis_final_LUCRIS.pdf

Bond & Amref. (2022). Who owns the story? Financial testing of charity vs participant led storytelling | Bond [Video]. Bond | the International Development Network. Retrieved October 28, 2023, from https://www.bond.org.uk/resources/who-owns-the-story-financial-testing-of-charity-vs-participant-led-storytelling/