My work on this blog progressed throughout October and first half of November 2023 – simultaneously with escalating Israel-Hamas conflict in the Gaza Strip. I am writing this using a laptop, which beyond having a simple function of a modern typewriter, inevitably is connected to the internet. This connectivity means that as I am sitting down over the research and making decision on my final blog post, literally every single news website or social media channel I look at is reporting that thousands lost their lives, that Hamas is holding over 200 hostages, that the Gaza Strip is under medieval siege, and the Israeli Defence Force is preparing for a land invasion. News and social media tabs on my screen are oozing blame shifting, accusations and counter accusations, as well as Islamophobia and antisemitism.

In my previous blog entries I looked at two different topics. First one was the research group Forensic Architecture – a blend of academia, cutting edge digital tools, and investigative journalism; all this harnessed in service of uncovering human rights abuses. The second was a lecture by Mathias Risse – Harvard University professor delving into the questions of truth and untruth, as well as broader query of what constitutes truth, and why untruths and half-truths are important in human live. Although seemingly both topics sit far apart, the intersection of them is the subject of truth, with emphasis of the role of truth in modern digital spaces. I consider this structural interrogation of meanings a very important part of understanding how the world is comprehended by various people coming from different backgrounds and experiences.

Thus, for this post I decided to take a brief hiatus from doom-scrolling, and instead use this space to reflect on media landscape, ICTs (Information and Communication Technologies), and personal and collective emotions expressed via ICTs. All this will be done in the context of recent escalation of enduring, emotionally charged and polarising Israel-Palestine conflict.

I will start with a brief dive into effect ICTs have on interhuman relations, followed by an exploration of emotional and political dynamics which shape collective and individual stances on such hotly contended issues as the Israel – Palestine conflict. I will then look at the current situation in ICTS, with emphasis on the Israel-Hamas conflict. Finally, I will look at some proposals on how to fix the current situation. I will also reflect on the possible future developments for ICTs and civil society in physical and digital spaces.

The accelerator

ICTs are no longer just a part of technological advancement that surround us; ICTs have become the driving force in many aspects of human life. Tim Unwin observed that ICTs are a ‘remarkable and powerful accelerator of human interaction’ (Unwin 2017: 150). Although Unwin talks about ICTs in the context of growing inequalities, this ‘powerful accelerator’ will escalate any interaction: no matter whether it’s social inequalities or call for collective punishment. Unwin continues with remarks on what he calls ‘the morality of internet’, which boils down to the fact that whether something is considered good or bad very much depends on the perspective of the viewer (Unwin 2017: 156).

The politics of empathy

This idea of perspective dictating what is good and what is bad begs for a question to be asked: how does one form a perspective on such a divisive issue as the Israel-Palestine conflict? In many cases the answer is quite simple: it is the emotions. Daniel Møller Ølgaard is his work The Technopolitics of Compassion talks about emotions in general, and compassion in particular, as the underlaying force of human behavior and perceptions of the world (Ølgaard 2022: 40).

Ølgaard argues that emotions should be perceived not only as ‘latent’ emotions – those felt and contained in individuals, but also (maybe even predominately) as ‘emergent’ emotions – those emerging from social and political life (Ølgaard 2022: 40). In other words, emotions are cultivated, performed, and given meaning by wider sociocultural processes and conditions (Ølgaard 2022: 40).

Only then emotions come to matter publicly and collectively, and then finally personally (Ølgaard 2022: 40). Emotions are political. And similarly, compassion is inherently political: it arises from politics rather than causes them (Ølgaard 2022: 40).

This idea of compassion (or lack of thereof) emerging from politics, will sound familiar to anyone who have ever spared a thought about human behavior during various conflicts: tribal or national disputes, religious wars, class struggle, the Holocaust, the Yugoslav wars of 1990s, and finally the Israel-Palestine conflict. Following from the notion that compassion is not the endogenous moral compass we often take it to be, but rather ‘a result of subtle forms of cultivation, power and governance’ it is important to think what exactly the ‘cultivation’ means (Ølgaard 2022: 40). Compassions’ ‘socio-political effects depend entirely upon the contexts and processes through which it comes to matter collectively, that is, beyond the disparate experience of individuals’ (Ølgaard 2022: 41).

This strongly echoes writing of Naomi Head who specifically looked at the empathy in the context of the Israel-Palestine conflict. Empathy, according to Head, is not a measurable constant, applicable in equal way to everyone and anyone. Empathy ‘is embodied, messy, personal, and political’ (Head 2015: 99). Just as the human perception of things can change, empathy also fluctuates and changes. It is shaped by the background of a person (both cultural and historical), as well as by the cultural and historical background of the community (Head 2015: 99). Realizing that such dynamic of empathy exists, means that every person is influenced by particular social, political, and cultural conditions. This in turn facilitates an understanding of what hinders or enables both individual empathy and broader empathy flows within and between societies (Head 2015: 99).

The fog of war

Could one risk the claim, that media technologies are one of the tools that could facilitate increase in individual empathy, as well as broader empathy between societies? It appears that at the current moment (middle of November 2023) it is safe to say that ICTs are supporting precisely the opposite attitudes. Media outlets, and particularly the online media, are becoming a potent tool in conducting disinformation warfare, stoking and causing ripple and after ripple of emotional upset.

This is what Shayan Sardarizadeh, a senior researcher working for BBC Monitoring (and a person whose daily work is to look at online misinformation and disinformation) said about X (formerly known as Twitter) in October 2023: ‘in the first couple of days of the conflict, the volume of misinformation on X was beyond anything I’ve ever seen’ (Suarez 2023). This volume of information that is highly charged with emotions (but difficult to corroborate) escalates every minute. New information and opinions, whether real, fake or just taken out of context, are spreading lightning fast online. Although many predicted that the use of AI generated imagery would be a large part of disinformation war, it seems that images taken out of context are the bigger problem:

‘Journalists and fact checkers struggle less with deepfakes than they do with out-of-context images or those crudely manipulated into something they’re not, like video game footage presented as a Hamas attack’ (Bedingfield 2023).

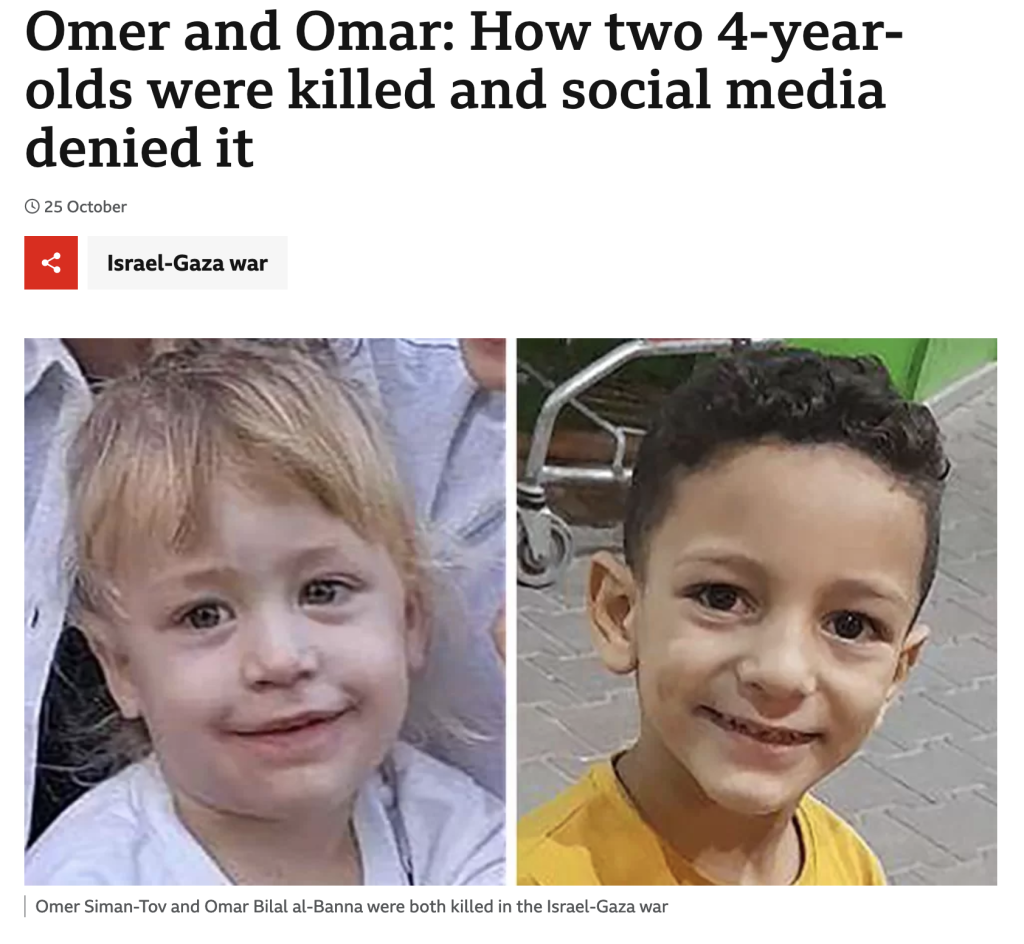

A poignant proof that successful spread of malignant, distressing, fake and viral information does not require sophisticated AI technology, is the story reported by the BBC about two 4-year-old boys (Spring 2023). Omar and Omer, one is Palestinian, the other one Israeli. Both were killed on the same day, both in the same area. But as BBC reported their deaths were not mourned online. Instead, a sickening, digital tug-of-war took place on social media, in which the deaths of the each one of the boys was denied by the opposed side. ‘It’s not a real baby; it’s a doll’ proclaimed one of the tweets on X (Spring 2023).

Is there a remedy?

At this point it is important to bring up again Unwin’s remarks about ICTs as a powerful accelerator of any human interaction. It seems that the accelerator of human interactions works quite well in escalating the bad interactions. In her work on fake news and disinformation Mel Bunce lists what has been attributed to online disinformation: ‘exasperating conflicts, hampering of humanitarian efforts to diminish consequences of a disaster, and inciting violence’ (Bunce 2019: 49, 51). These are the short-term effects, which one can already observe in the context of current Israel-Hamas conflict. But importantly for this text, Bunce also points to long-term impact that disinformation may have on ‘trust that citizens place in all sources of information’ (Bunce 2019: 51). This can have devastating effects on how news and essential information regarding the state of the world are treated and consumed. Research shows that audiences are confused and concerned about disinformation, and they struggle to know which sources of news to trust (Bunce 2019: 50, 51).

Is there anything that can be done to stop, or at least diminish this deluge of disinformation? Can we decelerate it? Or maybe even manage to accelerate the spread of truthful and trusted information? Bunce points at few things that in her opinion could be a remedy. One of them is media literacy. Bunce stresses the importance of audiences who ‘know how to distinguish sources that are trustworthy from those that are not’ (Bunce 2019: 53). Future education blueprints are the key in the ‘the global response to disinformation’ (Bunce 2019: 53). Bunce also mentions the issue of trust: ‘It is not clear exactly how online technologies will evolve and reshape humanitarian communications in the future’ (Bunce 2019: 54). But as she continues ‘we know that, in our new information ecology, trust is more vital than ever before. We must support media institutions and citizens as they seek out trustworthy sources’ (Bunce 2019: 54).

Bunce’s thoughts resonate with what Joan Donovan wrote in her reply to the report for UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Expression and Opinion. Donovan says that it is possible to create ‘an information ecosystem that promotes truth over sensationalism, accuracy over popularity, and can additionally be subject to more effective oversight’ (Donovan 2021: 3).

Donovan says that curbing the online disinformation is necessary for upholding the freedom of expression, since spreading deliberately false or misleading information directly impedes the right to freedom of expression (Donovan 2021: 3). The debate over how to stop disinformation includes several proposed remedies to ensure compliance to site policies, local norms, and the law. ‘In this debate, two words often come to mind: moderation and curation’ (Donovan 2021: 9). Donovan puts forward proposals such as community based proactive content curation (Donovan 2021: 11), this in turn would involve transparency, durability, multi-stakeholder engagement, infrastructure that encourages democratic participation and accountability (Donovan 2021: 13, 14).

Around the corner: a turning point or the nuclear doomsday?

Chouliaraki in her writing on the history of humanitarian communication talks about the way newspapers and television reported on the 1968 war in Biafra, as of ‘a historical turning point’ in global humanitarianism: shocking images of starving children were appearing before audiences’ eyes – thanks to new technologies available to many in the West (Ølgaard 2022: 42).

Are we looking at a new turning point in how conflicts are shown in new and old media? Possibly, although it is difficult to say how exactly will it affect our future relationship in how conflicts are portrayed, and how we interact with information that is emotionally charged and possibly untruthful. Have we just crossed the new frontier of polarizing human emotions? Looking at the social media feeds, legacy media’s opinion pieces, or governments’ websites I think there is no doubt we have reached new and uncharted territory.

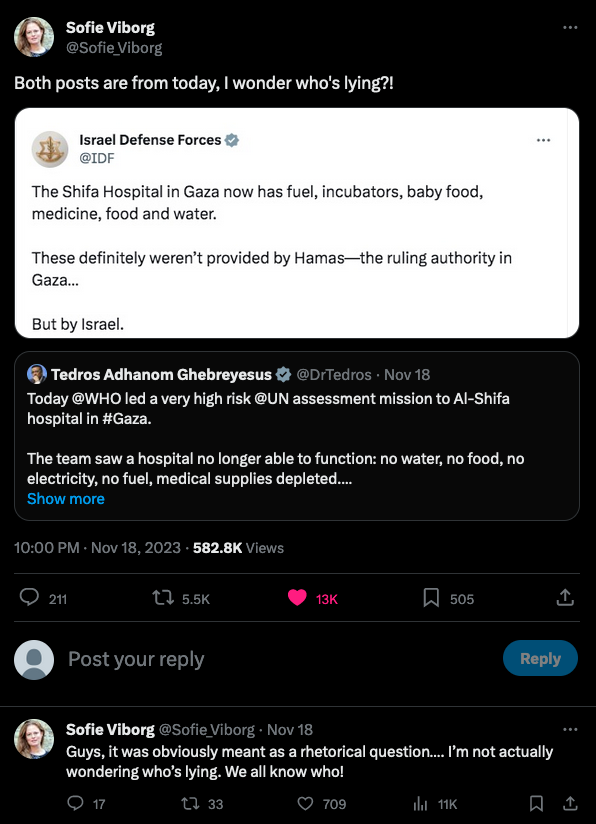

The accountability and moderation for which Joan Donovan called, seems to be buried deep under an avalanche of claims and counterclaims. Like this interview with Israeli President Herzog claiming that Gaza’s al-Shifa hospital was not bombed (BBC:2023), While at the same time various media reported fighting near and inside the grounds of Gaza’s hospitals; including the al-Shifa (Sinmaz, Burke 2023).

Reading the hair-raising interview with Daniella Weiss – the head of Israeli settler movement– won’t fill any hearts with hope for peaceful and reconciliatory end to the conflict (Chotiner, 2023). In fact, the world may have just inched a step closer to a nuclear conflict as Amihai Eliyahu – Israel’s Minister of Heritage – suggesting that dropping a nuclear bomb on Gaza Strip is an option for Israel (Lederer, 2023).

The uncharted territory ahead.

Predictably, many speculate on how the current conflict ends, but also what is the more distant future for the Israel-Palestine conflict. Some anticipate that, paradoxically, the current violent escalation will renew the international efforts for establishment of two sovereign states somewhere between the Jordan river and the Mediterranean Sea (Tisdall, 2023). Some others argue that the two-state solution, which for decades has been viewed as the end goal of peace efforts in the conflict, is now dead (Khalidi, 2023). There are voices suggesting that a peacekeeping force (led by the Arab nations) should be present in the Gaza Strip (Mackinnon, 2023). There are warning about the conflict spilling over the borders into the wider Middle East (Kurtzer-Ellenbogen, 2023).

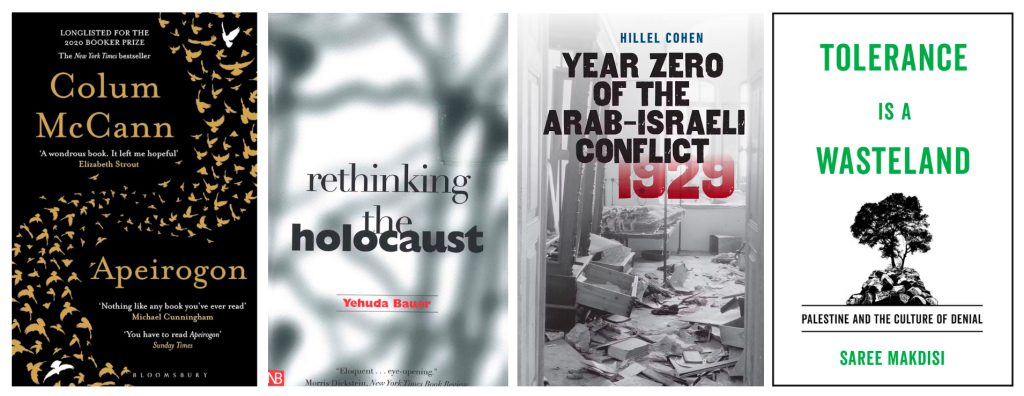

What lays ahead for the ICTs seems to be equally unknown. There are calls for more verification of social media and news outlets (Mukherjee, 2023). So emotionally charged had the conflict become, that reports emerged of social media companies blocking accounts of people who may be supporting one of the sides (Thakker, Biddle 2023). Some analysis point out that simplified information presented on social media is not the way to learn about such complex issue (Vlamis, Snodgrass 2023). And interestingly, one can find lists of books recommended for those wanting to understand the roots of the conflict (Conversation 2023).

And understanding the origins of what is happening in the Middle East, may be the first step towards reconciliatory solution. Returning to Naomi Head’s acute observations about empathy, it is worth quoting in length a passage that is still very timely, despite being published in 2015:

In the Israel-Palestine conflict (…) what stands in the way of recognizing other human as a human being? Parties in intractable conflicts tend to establish monolithic identities for themselves and the other, which are bolstered by historical narratives recruited for such a purpose. There is little scope for revealing vulnerability to the other within such identities and narratives that shape (and obscure) the capacity for recognition of the other’s narrative and identity (Head 2015: 105).

Cultivation of ‘established monolithic identities’ and ‘historical narratives recruited for that purpose’ will do no less, than facilitate further entrenchment in one-sided empathy. Which in turn absolves ones’ side of the narrative from any evil doing, while simultaneously accusing the other side of the narrative of all the possible evil deeds. Departure from one-sided empathy needs changes at the individual level, towards mutual acceptance and understanding. It needs a transformation of the emotional conflict of absolute truths that the Israel-Palestine war has become (aside of the conflict of physical violence and emotional terror) towards a space where it is possible, for both sides, to embrace ‘a recognition of the history of both Israelis and Palestinians, of the Holocaust and the Nakba‘ (Head 2015: 107).

Ideally, for anyone looking at the current escalation of the decades-long conflict, the obvious route towards some sort of satisfying ending would be a drive to reconciliation. The start of anything that resembles non-hostile relations, would hopefully enable both sides to ‘acknowledge how each side has contributed to the suffering of the other and breaks down the ‘absolute conviction in one’s own victimhood’ (Head 2015: 71). Only by addressing the suffering on all sides can we comprehend what is happening – and what can come next. Empathy involves recognizing others as human beings, whether on a personal or community level (Head 2015: 99). Again, a poignant remark from Naomi Head: ‘as one Palestinian explained, ‘we must teach Israeli Jewish children about the Nakba and Palestinian children about the Holocaust’ (Head 2015: 108). Can ICTs help with achieving it, or are they just a tool of sowing hatred? I think there is a real potential for ICTs as a tool of education and a platform for reconciliation. The pressing questions are how it will be achieved, and what can be done to minimize the harmful spread of disinformation and untruths online. Unfortunately I predict that in the coming months and years, we will more frequently see audiences who are confused, suspicious, or even cynical about which sources of online information are trustworthy and which one are not.

https://twitter.com/Sofie_Viborg/status/1725982324997619864

It is important to mention that writing of this text was concluded on 22nd November 2023, and remained unchanged since then, despite many developments in the Israel-Hamas conflict.

Bibliography

BBC (2023). Israel’s president denies it is striking Gaza’s Al-Shifa hospital. Available from: https://bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-67397963. (Accessed 13 November 2023).

Bunce, M. (2019). Humanitarian Communication in a Post-Truth World. Journal of Humanitarian Affairs, 1(1), 49-55. Retrieved November 1, 2023, from https://doi.org/10.7227/JHA.007

Bedingfield, W. (2023). Generative AI Is Playing a Surprising Role in Israel-Hamas Disinformation. The Wired. Available at: https://wired.co.uk/article/israel-hamas-war-generative-artificial-intelligence-disinformation (Accessed 1 November 2023).

Chotiner, I. (2023). The Extreme Ambitions of West Bank Settlers. The New Yorker. Available from: https://www.newyorker.com/news/q-and-a/the-extreme-ambitions-of-west-bank-settlers (Accessed 15 November 2023).

Conversation (2023). 10 books to help you understand Israel and Palestine, recommended by experts. Available from: https://theconversation.com/10-books-to-help-you-understand-israel-and-palestine-recommended-by-experts-217783 (Accessed 22 November 2023).

Donovan, J. (2021). Disinformation at Scale Threatens Freedom of Expression Worldwide. Harvard Shorenstein Center. Available from: https://ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Issues/Expression/disinformation/3-Academics/Harvard-Shorenstein-Center.pdf. (Accessed 1 November 2023).

Head, N. (2015). A politics of empathy: Encounters with empathy in Israel and Palestine. Review of International Studies 42 (1): 95-113

Khalidi, A. S. (2023). As a former Palestinian negotiator, I know Biden’s two-state solution is sheer delusion. The Guardian. Available from: https://theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/nov/11/as-a-former-palestinian-negotiator-i-know-bidens-two-state-solution-is-sheer-delusion. (Accessed 16 November 2023).

Kurtzer-Ellenbogen, L. (2023) What’s Next After Hamas’ Attack on Israel? United States Institute of Peace. Available from: https://usip.org/publications/2023/10/whats-next-after-hamas-attack-israel (Accessed 1 November 2023).

Lederer, E. M., (2023). Nations Condemn Israeli Minister’s Comments About Dropping Nuclear Bomb on Gaza. The Time. Available from: https://time.com/6334812/israeli-minister-nuclear-bomb-gaza-condemnations/ (Accessed 14 November 2023).

Mackinnon, A. (2023). What Happens to Gaza after the War? The Foreign Policy. Available from: https://foreignpolicy.com/2023/11/03/what-happens-gaza-war-aftermath-palestinian-future/ (Accessed 11 November 2023).

Mukherjee, M. (2023). Israel-Gaza conflict: when social media fakes are rampant, news verification is vital. The Conversation. Available from: https://theconversation.com/israel-gaza-conflict-when-social-media-fakes-are-rampant-news-verification-is-vital-215496 (Accessed 1 November 2023).

Ølgaard, D. M. (2022). The Technopolitics of Compassion: A Postphenomenological Analysis of the Digital Mediation of Global Humanitarianism. [Doctoral Thesis (monograph), Department of Political Science]. Lund University.

Sardarizadeh S. [Twitter]. Available at: https://twitter.com/Shayan86. (Accessed 15 October 2023).

Sinmaz, E., Burke, J. (2023). Israeli soldiers raid al-Shifa hospital in escalation of Gaza offensive. The Guardian. Available from: https://theguardian.com/world/2023/nov/15/idf-entered-gaza-al-shifa-hospital-raid-targeted-operation-hamas (Accessed 15 November 2023).

Spring, M. (2023). Omer and Omar: How two 4-year-olds were killed and social media denied it. BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-67206277 (Accessed 27 October 2023).

Suarez, E. (2023): BBC expert on debunking Israel-Hamas war visuals. Reuter Institute. Available at: https://reutersinstitute.politics.ox.ac.uk/news/bbc-expert-debunking-israel-hamas-war-visuals-volume-misinformation-twitter-was-beyond (Accessed 1 November 2023).

Thakker, P., Biddle, S. (2023). TikTok, Instagram Target Outlet Covering Israel–Palestine Amid Siege on Gaza. The Intercept. Available from: https://theintercept.com/2023/10/11/tiktok-instagram-israel-palestine/ (Accessed 12 November 2023).

Tisdall, S. (2023). Israel is in a fight to the finish. Whatever comes next, it must change. The Guardian. Available from: https://theguardian.com/commentisfree/2023/oct/28/israel-is-in-a-fight-to-the-finish-whatever-comes-next-it-must-change. (Accessed 2 November 2023).

Unwin, T. 2017: Reclaiming Information & Communication Technologies for Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Vlamis, K., Snodgrass, E. (2023). Social media isn’t going to solve the Israel-Hamas war. Business Insider. Available from: https://businessinsider.com/social-media-posts-oversimplify-israel-hamas-war-2023-10 (Accessed 2 November 2023).