An essay about governments’ usage of internet shutdowns and bots as tools to silence activist voices online and what effects these have on society.

Introduction

Some governments openly embrace the use of social media activism to, for example, rally support from their voters or try to get the population engaged in important discussions. However, in certain cases social media activism has had the power to overthrow governments.

A paper that studied the effect of social media during the Arab Spring concluded that:

“the bulk of the research contends that social media enabled or facilitated the protests by providing voice to people in societies with mostly government-controlled legacy media; helping people connect, mobilise and organise demonstrations”

(Smidi & Shahin, 2017. p. 1)

One method employed by governments threatened by the use of social media as a foundation for activist movements is to restrict the internet in its entirety. Another tool some governments use to quell critical voices or change people’s opinion on topics is through the use of bots. This tool is more indirect and could give people the perception that the government does not interfere with their activist attempts, whilst they are. This text will explore why governments choose to take this path and the effects that this has on a country’s population.

Research question and method

This paper is a literature study that seeks to compile the current theories and debates that scholars have about this topic. The questions that will guide the focus of the text are related to how governments fight online activism. The three main questions are:

How do internet shutdowns and the use of bots attempt to silence activists?

What are the consequences of these tools on society?

How do activists resist these methods?

Methods to silence activists

When it comes to the methods of silencing activists online there are usually two routes that a government can take: overtly or covertly. An overt strategy can be methods such as an internet shutdown whilst the use of bots is more difficult to detect and can be seen as covert (Earl et al., 2022). This section will discuss the two phenomena and present the implications of them.

Internet shutdowns

There is a typology when it comes to discussing internet shutdowns where it can be a “complete shutdown of all internet traffic nationwide” or “take the form of a partial shutdown of a single website or a specific district” (Anthonio & Roberts, 2023). However, the goal is still the same for the two types; it is meant to silence and quell voices expressed online. Essentially what the governments are afraid of, in many cases, is that critical opinions online will spill over into everyday life and lead to protests and demonstrations that challenge the rule of those in power.

Photo: Ricardo Arce/Unsplash

There is evidence that internet shutdowns do have the intended effect when it comes to stopping protests. One study mentions that initially there is an increase in protests when the internet is shut down, but after the first week it can lead to “a digital siege” which leads to fewer protests (Rydzak, 2018. p. 14). However, what will be discussed here is not only the impact it has on activists and citizens trying to protest, but also the society.

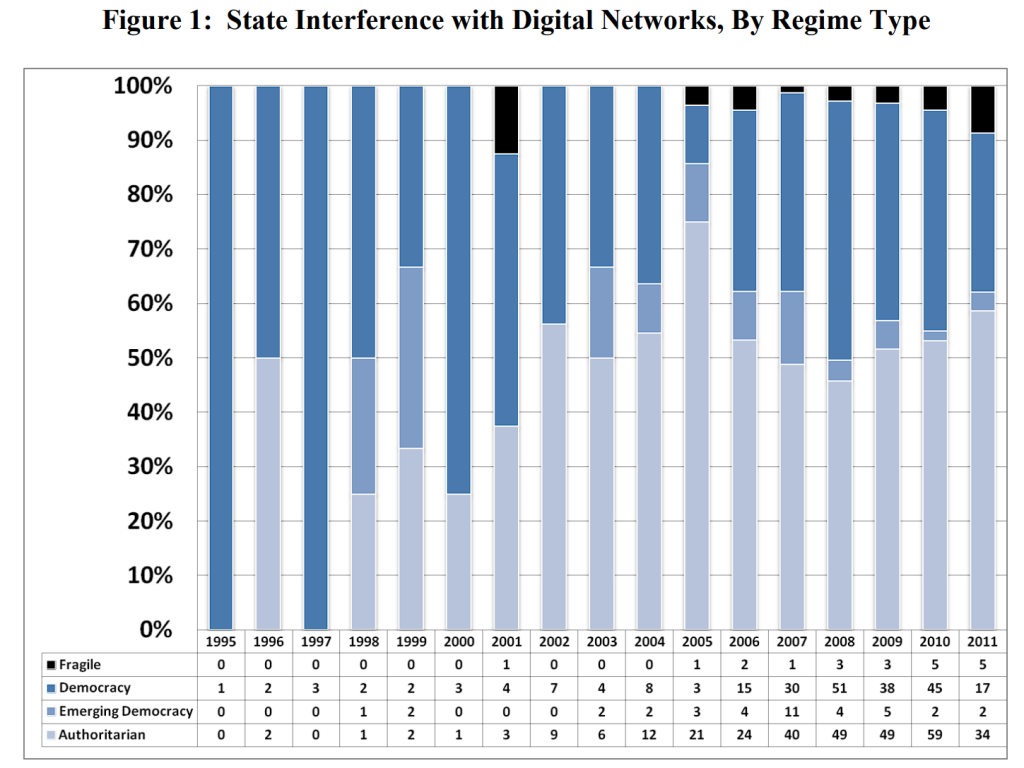

Figure 1 was taken from a research paper published in 2011, and it identified that “after 2002, authoritarian regimes clearly began using such interference [internet shutdowns of some form] as a tool of governance” (Howard et al., 2011. p. 6).

The internet shutdowns have not slowed down since then and can still be seen today (Rosson et al., 2023). The midyear report of 2023 created by Access Now shows that there has been “at least 80 shutdowns across 21 countries” (Rosson & Anthonio, 2023).

One big issue with a general internet shutdown is that, as John Palfrey at Harvard Law School argues, ”there’s a huge tension between the importance of the Internet for ‘benign’ activities like economic and social uses and its more controversial political activities.”(Greenberg, 2011). Essentially, one could call these internet shutdowns a form of ‘collective punishment’ that have severe implications on everyday life for citizens.

There are reasons for why internet shutdowns might have unintended consequences for the governments that seek to implement them. The internet undoubtedly has a large economic benefit for a country and millions of people depend on it. This analysis needs to include factors such as that “hospitals and factories lost access to online information, thereby undermining productivity and potentially costing jobs and lives” which comes to show that this indiscriminate tool can essentially cripple the country that chooses to use it (West, 2016. p. 1).

This is one of the reasons for why we see the rise in the usage of bots when it comes to the attempts to silence activists.

Bots

During the wave of protests in Egypt in 2011, the sitting President Hosni Mubarak attempted to censor the internet which brought along condemnation from world leaders and eventually failed (Greenberg, 2011). Since the attempts to censor the internet “governments have made great advances in devising more sophisticated methods to neutralise those who would use the internet digital tools against them, and even to use it to mobilise populations for their own interests.” (Tufekci, 2017. p. 226).

One such advancement in technology, which governments around the world use to silence online activists or critical voices are bots. Bots are essentially “automated programmes” that “are often designed to mimic human users” (Cloudflare, u.d.). In today’s digital landscape, it is not hard to find social media bots. For example, they are often used to promote products or to get users to click malicious links. Some of these bots are easy to spot even for the untrained eye. Experts say “that more than 10 precent of content across social media websites (…) is generated by bots” (Woolley, 2017. p. 13).

However, the governments that use these tools often seek to spread disinformation and rumours in more covert ways.

Overall, the use of government supported bots goes in line with what Tufekci mentions in their paper about the government’s use of repressive tools which are more covert than internet shutdowns (Tufekci, 2014). Tufekci notes that “their methods are to demonize social media, so their supporters who are not already on social media remain away and those supporters who are already on social media use the platform to voice their support for the government.” (Tufekci, 2014. P. 7).

A study made on Russian bots was published in 2022 in the American Political Science Review. The study mentions how “bots might seek to change the public perception of regime popularity” or can be used directly to “harass and threaten opposition activists” (Stukal et al., 2022. p. 846). The study goes on to say how human ‘trolls’ online might provide a more direct effect when it comes to targeting opposition activists online. The sheer mass of bots could induce another kind of fear. For example, opposition activists being slandered “at scale” with “compromising information hacked from their email accounts” (Stukal et al., 2022. p. 846).

The study also tested the hypothesis of whether they could see an increase in bots retweeting “a wider range of accounts during specific days” to “increase the diversity of the retweeted sources on protest days and days with high online opposition activity” (Stukal et al., 2022. p. 851). The results supported this ‘flooding’ hypothesis, whereby bots try to smoother online and offline opposition.

What effects can then be seen on the users interacting with these bots? At least when it comes to the ‘stance’ that social media users take on certain issues, Aldayel & Magdy’s study (2022) proved that bots can influence these.

This indicates that bots have multiple ways which they can be used to influence social media activism. On one hand they may target key people and overwhelm them with content or smear campaigns; on the other hand they can try and persuade users directly to not believe in activist causes.

The ways activists respond to these methods

When it comes to internet shutdowns, they are still prevalent in the world as the Access Now report of 2022 stated (Rosson et al., 2023). What is interesting to discuss is how activists during the protests in Egypt 2011 responded to the internet shutdown that was enforced then as it could provide insight into how it can be combated by activists today. The protests in Egypt, and the subsequent decision by the president to shut down the internet, is a reason why “modern governments rarely attempt” such methods nowadays (Tufekci, 2014. p. 7).

“Within hours, activists had pierced this censorship by using smuggled satellite phones, a few remaining Internet connections, and other methods of circumvention, and had reconnected with the rest of the world, even if at a much narrower bandwidth” (Tufekci, 2014. P. 7)

Technical solutions such as VPNs are commonly used to circumvent localised internet shutdowns, and scholars use it as a recommendation for how citizens can “recover their digital citizenship” (Anthonio & Roberts, 2023). Even complete internet shutdowns can be avoided through the use of satellite dishes which establishes a satellite connection to avoid having to go via the internet service provider (Anthonio & Roberts, 2023). This tactic was used in Iran with the creation of Toosheh whereby users could connect their computers to a satellite dish to “download one gigabyte of readily made content” (Centre for Human Rights in Iran, 2016). On top of this, the use of “mesh networks” that uses radio frequencies and “international SIM cards with roaming services” are all recommendations for activists trying to get their voice heard in times of complete internet shutdowns (Anthonio & Roberts, 2023).

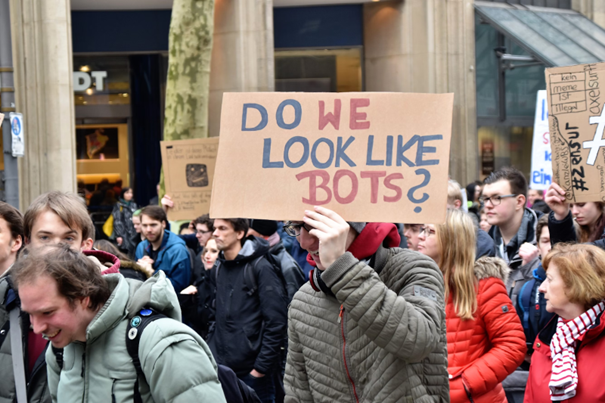

When it comes to the use of bots by governments that attempt to undermine activist movements it becomes more complicated. As previously mentioned, internet shutdowns are overt and are felt throughout society, but bots are more covert and are sometimes undetectable. Online regulation and laws are usually discussed in relation to social media bots and the complex nature of trying to handle an issue such as this comes to light. When discussing the legislation around social media bots in the US Stricklin & McBride mention that “There is no clear path forward, though, and it is unlikely that Congress will find a legislative solution to this problem in the near future.” (Stricklin & McBride, 2020. p. 24). However, a paper that studied climate activists and how bots were used to spread both activism and scepticism suggested that a way to decrease the effects of bots on public discourse is to cultivate “individuals’ media literacy in terms of distinguishing malicious social bots as a potential solution to deal with social bot skeptics disguised as humans.” (Chen et al., 2021. p. 921). Even though this example did not in detail explore the use of government sponsored bots to silence critics, it exemplifies the complex nature of the issue and the difficulty in regulating it.

Conclusion

In this article, I’ve discussed how governments can silence activists online overtly through restricting the internet access, or covertly by implementing bots.

One key trend I found when reading the articles written on the matter, and that was that the damage done by complete internet shutdowns is a double edged sword. On one hand it can lead to less protesting, but on the other it carries with it big socio economic issues. With this we see a rise in the use of government supported bots that seek to undermine activist movements.

Overall, there are several methods that activists can use to circumvent internet shutdowns as the paper explains. However, bots online are harder to work against and the main method identified to avoid these bots’ influence on social movements is to increase media literacy.

Activists online need to be aware of these risks and the methods that governments use to try and hinder their work to remain a driving force for social change in countries where the governments will crack down on their efforts.

Concluding reflections on the blog work

From the start of this assignment (the entire work on the blog) my area of interest has been on the reactions of governments when discussing internet activists. What fascinated me the most was the repressive tools used by governments to silence activists and explore the trends that can be seen in the 21st century.

This task gave me the chance to introduce more diverse literature on the topics that I have explored in the previous blog posts. It provided me with an opportunity to respond to some of the comments and feedback I had been getting in the comments on the previous posts, which had me thinking in different directions. The previous blog posts were kept rather brief and straight to the point to make the content fit with the medium, in this case being a blog about digital trends. For this longer text it was possible to explore more academic routes and really dwell deep into what scholars are researching when it comes to this topic.

Overall, the group work dynamic has been beneficial when it comes to brainstorming and topics with each other. The feedback received from other groups as well as the team members of this blog has helped with expanding my research topic as well as exploring certain aspects which I did not think of myself when I started this writing journey.

Bibliography

Aldayel, A., & Magdy, W. (2022). Characterizing the role of bots’ in polarized stance on social media. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-022-00858-z

Anthonio, F., & Roberts, T. (2023). Internet shutdowns and digital citizenship. Digital Citizenship in Africa. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350324497.0011

Center for Human Rights in Iran. (2016, March 18). New app lets Iranians download information via satellite and bypass state’s internet censorship. https://iranhumanrights.org/2016/03/toosheh-mehdi-yahyanejad/

Chen, C.-F., Shi, W., Yang, J., & Fu, H.-H. (2021). Social Bots’ role in climate change discussion on Twitter: Measuring standpoints, topics, and interaction strategies. Advances in Climate Change Research, 12(6), 913–923. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accre.2021.09.011

Cloudflare. (n.d.). What is a social media bot?. https://www.cloudflare.com/learning/bots/what-is-a-social-media-bot/

Earl, J., Maher, T. V., & Pan, J. (2022). The digital repression of social movements, protest, and activism: A Synthetic Review. Science Advances, 8(10). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abl8198

Greenberg, A. (2011, February 2). Mubarak’s digital dilemma: Why Egypt’s internet controls failed. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/andygreenberg/2011/02/02/mubaraks-digital-dilemma-why-egypts-internet-controls-failed/?sh=d01ce321953b

Howard, P. N., Agarwal, S. D., & Hussain, M. M. (2011). The Dictators’ Digital Dilemma: When Do States Disconnect Their Digital Networks? Issues in Technology Innovation.

Rosson, Z., & Anthonio, F. (2023, July 31). Internet shutdowns in 2023: A mid-year #KeepItOn update. Access Now. https://www.accessnow.org/publication/internet-shutdowns-in-2023-mid-year-update/

Rosson, Z., Anthonio, F., Cheng, S., Tackett, C., & Skok, A. (2023, May 24). Internet shutdowns in 2022: The #KeepItOn report. Access Now. https://www.accessnow.org/internet-shutdowns-2022/

Rydzak, J. A. (2018). A Total Eclipse of the Net: The Dynamics of Network Shutdowns and Collective Action Responses. The University of Arizona ProQuest Dissertations Publishing.

Smidi, A., & Shahin, S. (2017). Social Media and social mobilisation in the Middle East: A survey of research on the Arab Spring. India Quarterly: A Journal of International Affairs, 73(2), 196–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/0974928417700798

Stricklin, K., & McBride, M. K. (2020). (rep.). Social Media Bots: Laws, Regulations, and Platform Policies.

Stukal, D., Sanovich, S., Bonneau, R., & Tucker, J. A. (2022). Why Botter: How Pro-Government Bots Fight Opposition in Russia. American Political Science Review, 116(3), 843–857. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055421001507

Tufekci, Z. (2014). SOCIAL MOVEMENTS AND GOVERNMENTS IN THE DIGITAL AGE: EVALUATING A COMPLEX LANDSCAPE. Breaking Point: Protests and Revolutions in the 21st Century.

Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protest. Yale University Press.

West, D. M. (2016). Internet shutdowns cost countries $2.4 billion last year . Center for Technology Innovation.

Woolley, S. C. (2017). COMPUTATIONAL PROPAGANDA AND POLITICALBOTS:AN OVERVIEW . Can Public Diplomacy Survive the Internet? Bots, Echo Chambers, and Disinformation.