Introduction:

For the past month, I have been exploring how Generation Z (Gen-Z) use humour in their digital activism.

This was in part inspired by a quote by Zeynep Tufeckci in her book, Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. She writes, “the expressive, often humorous style of networked protest attracts many participants and thrives both online and offline, but movements falter in the long term unless they create the capacity to navigate the inevitable challenges”.[i]

Tufekci is correct that activist movements encounter many challenges when turning their online and offline activism into tangible change. For the youth-led movements I’ve analysed through my research, the challenges that Tufekci outlines are often magnified because participants can sometimes be too young to vote or run for political office and lack the seniority to be taken seriously in political discussions or negotiations.[ii] Indeed, an entire thesis could be written on the fragility of youth-led movements and their digital activism.

Instead, for this academic post, I want to discuss the first part of her statement – how does the often-humorous style of Gen-Z’s digital activism attract participants, and does it cause more harm than good in the long run?

In my previous posts, I defined Gen-Z as digital natives for whom social media is an essential part of their activism and explored how youth-led activist groups like A March for Our Lives and Fridays for Future use humour with varying degrees of success. Therefore, this post will focus on the benefits and risks of using humour in their digital activism, including whether humour can support better representation and how colonialism even affects memes.

The benefits of humour in digital activism

Humour can create a sense of community for Gen Z activists.

As outlined in this post, Gen-Z operates in a hybrid activist space where their online activity is “seamlessly integrated with (their) offline lives, augmenting and interweaving with, but not replacing face-to-face activism”.[iii] For Gen-Z activists, social media is a tool to increase the visibility of their causes, cultivate their activist identity, and build their activist network beyond immediate friends and family.[iv] This hybridity has facilitated a sense of community amongst Gen-Z activists that occurs at multiple levels, “from the hyperlocal to the transnational, from friendship circles to social movements and formal organisations.”[v]

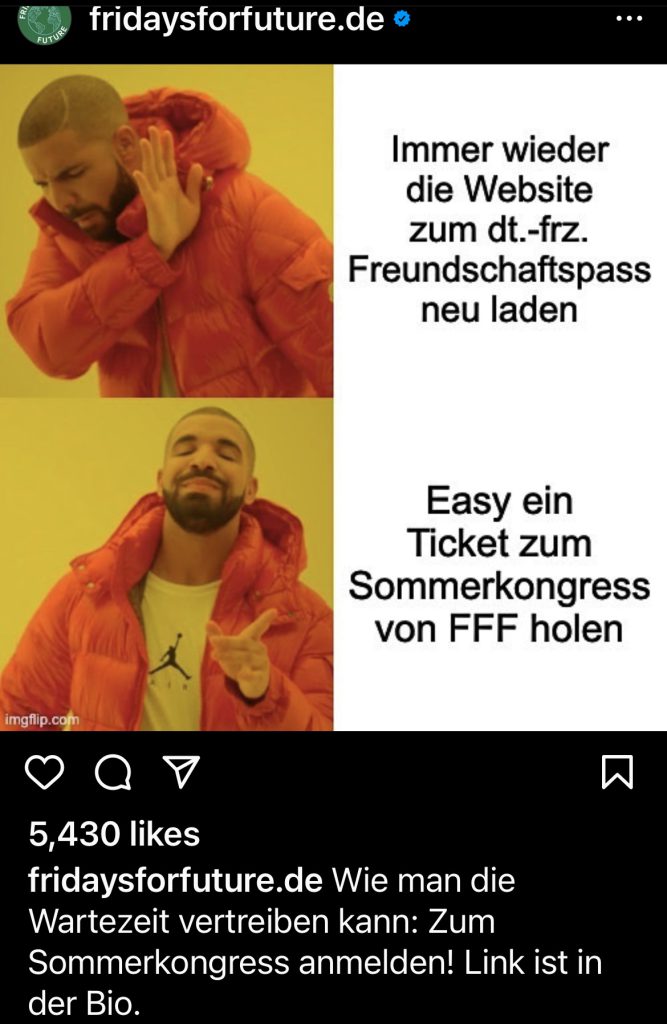

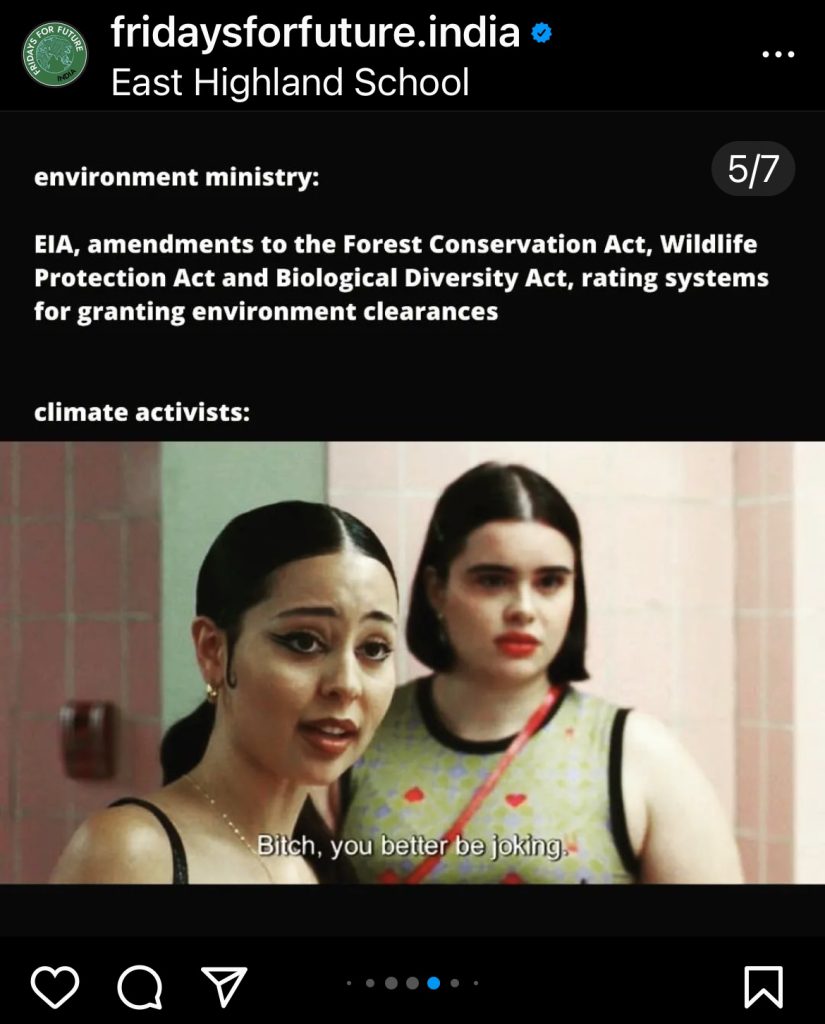

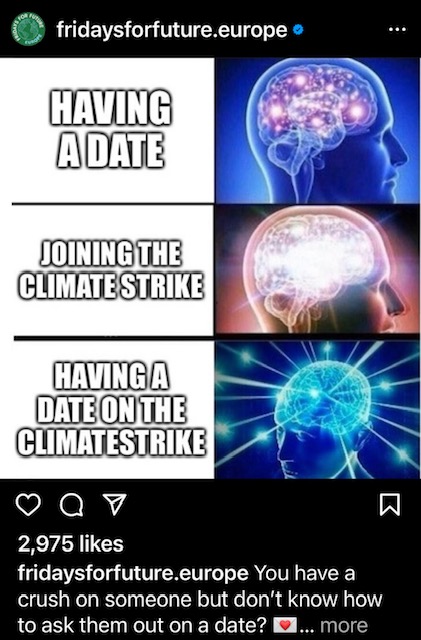

The use of humour – especially through memes – has been an effective community-building tactic for Gen-Z as demonstrated by the following examples of memes used by the Indian, German, American, and Swedish chapters of the Fridays for Future movement.

Memes are defined by Limor Shifman as “units of popular culture that are circulated, imitated, and transformed by individual Internet users, creating a shared cultural experience” and as “groups of content items that were created with an awareness of each other and share common characteristics”.[vi]

In her in-depth analysis of memes as a form of cultural globalisation, Shifman theorises that since memes both “represent and construct social perceptions” and are easily shared across borders, “they may facilitate the creation of global digital cultures”.[vii] This aligns closely with Stuart Hall’s theory of representation which defines representation as “the production of meaning through language” and although we each understand and interpret the world in unique ways, we can communicate because we have a “shared culture of meanings”.[viii] In a way, memes are a new language through which we communicate and they are reliant on a shared culture of meanings to make sense or to be funny.

Shifman also argues that memes have gone beyond entertainment and are increasingly “used for an array of purposes such as…community building and political protest”.[ix] Memes are particularly well-suited to community building because to find a meme funny, you must be ‘in’ on the joke.[x] This also aligns with Hall’s theory of encoding/decoding. One could argue that in the process of developing and sharing memes, Gen-Z activists are encoding their memes with meaning – ideologies, values, and messages related to their causes – and with their circulation through digital media, the memes are then received, understood or interpreted by their audiences.[xi] When an audience correctly interprets or ‘decodes’ the meme, it can create a sense of community or closeness because they have understood the original intent of the meme-maker and are ‘in’ on the joke too.

However, one could also argue memes are exclusionary and work against community-building. Decoding memes requires shared cultural references which could exclude audiences who may not have access to these cultural touchpoints. Further to this, Western culture dominates most meme formats.[xii] Indeed, every meme listed above uses cultural references from North America such as Drake (a Canadian rapper), Spongebob Squarepants (an American cartoon), or Euphoria (an American TV show). To understand them, you would need to be able to access English-language rap music or be able to watch American TV shows. For marginalised communities in the Global South, this might not be possible and could mean that they are excluded from the humour behind the meme, and thus excluded from these online activist communities.

However, Shifman argues that whilst meme templates are dominated by Western culture, “these references are often used merely as wallpapers, backgrounds for local happenings.”[xiii] Although audiences outside of the Global North may not have access to the references used in most meme templates, they still understand the context behind the template and can infuse them with their own meaning related to local events. This is demonstrated by the meme used by Fridays for Future India which uses a Euphoria meme template to ridicule Indian environmental policies.

Humour can engage audiences with emotion and help activists avoid burnout.

Social movement scholars have long argued that emotional engagement is a powerful motivator in getting people involved in activism.[xiv] Therefore, it can be argued that humour is an effective tactic for Gen-Z in engaging or mobilising people to their cause because it can trigger emotional responses and make learning about activist causes more enjoyable.[xv]

Several studies have shown that comedy is the best way to engage or persuade individuals who have little interest in climate change.[xvi] When audiences are bombarded with facts, statistics, or future-oriented projections, they are more likely to feel overwhelmed or hopeless.[xvii] This can make them switch off or disengage from the topic. In contrast, humour can make this content “stick out” because it requires attention to “decode” it correctly and audiences are more likely to invest their time in the promise of a “pleasurable affective jolt” within their bodies, such as when they laugh or smile.[xviii] A positive emotional connection with a cause can make audiences feel more empowered to act on it.

Building on this, humour can help protect Gen-Z activists from burnout. Many activists can suffer from stress-related “burnout” which manifests itself in physical or mental health symptoms.[xix]. Humour can protect against both. Laughter has been shown to support “muscle relaxation”, the reduction of cortisol and blood pressure levels, and a heightened immune system”.[xx] From a mental health standpoint, the pleasure of “gallows humour” can provide “comic insulation” against overwhelmingly negative emotions such as despair.[xxi]

Humour can circumvent algorithms and bypass censorship.

The emotional response that is triggered because of the use of humour can also help Gen-Z activists circumvent the algorithms that control the visibility of activist content on social media platforms.

Ad-financed social media platforms like Twitter, Facebook, and TikTok, can sometimes “drown out” activist messages in favour of more advertiser-friendly content or content that will trigger more user engagement through likes, views, and comments.[xxii] These platforms rely on algorithms to decide what to “surface” and what to “bury”.[xxiii] The more engagement that a piece of content has, the more likely it is to show up on more users’ feeds because the algorithm thinks it is important content. This makes it more likely that the content will get more engagement, creating a feedback loop. The fewer likes or views that content has, the more it is hidden from users, making it less likely to show up on users’ feeds and less likely to get engagement.

Gen-Z activists are greatly attuned to this issue and use humour to trigger user engagement that helps them bypass algorithms.[xxiv] As digital natives, they inherently understand that platforms reward novel, emotive or entertaining content.[xxv] By making their activist content softer and more entertaining through humour, Gen-Z activists are more likely to trigger user engagement that signals to these platforms that their content is important and should be prioritised.[xxvi]

Further to this, humorous content can also help Gen-Z activists bypass online censorship. Authoritarian governments often monitor social media for dissent and demand the removal of critical content from these platforms.[xxvii] In these environments, humour and memes have been used by activists to disseminate political narratives that “oppose dominant state discourses”.[xxviii] By obscuring their political intent through humour, memes can help activists fly under censorship radars and avoid the repercussions they would face if they were to discuss their views openly in traditional formats.[xxix] As outlined earlier, to understand a meme, you have to know the broader context and be ‘in’ on the joke. This ambiguity makes it hard for governments to catch this subtext and in restricted media environments like China and Russia, memes have flourished as a tool for political deliberation or dissent.[xxx] However, governments are increasingly censoring memes. For example, China now regularly censors the use of Winnie the Pooh cartoons on social media because popular memes used the cartoon to mock President Xi Jinping.[xxxi]

The risks of humour in digital activism

Humour can trivialise serious issues.

Many Gen-Z activists are working on serious issues such as climate change, gun safety, or sexual violence. When considering the seriousness of these topics, humour risks trivialising them.[xxxii] For example, this Valentine’s Day meme from Fridays for Future Europe [DB2] suggests that the climate strike is a perfect environment for a date. However, considering the climate strike was started by Greta Thunberg to channel her extreme eco-anxiety, memes or jokes like this in activism can be seen as detracting from the seriousness of an issue or cause.[xxxiii]

Humour is subjective and risks backlash

Another risk in the use of humour in activism is that it is subjective. Jokes can be interpreted in many ways, and it is often difficult to determine what makes humour “succeed or fail in a particular situation”.[xxxiv] Gen-Z activists cannot predict what online reaction their meme or humorous post will elicit. Indeed, even as a meme sparks positive responses from one audience, it could encounter fierce resistance from another.[xxxv]

This is particularly acute when sharing their content online as content produced for one audience that is ‘in’ on the joke can be easily accessed by other audiences, including those that are hostile to their cause or ignorant of the joke’s original intent.[xxxvi] This is called “context collapse” and happens when content that is crafted to speak to the shared assumptions or norms inside a group is made public to those who are ‘outside’.[xxxvii] Those on the ‘outside’ can react negatively without the relevant context to be ‘in’ on the joke.

The use of humour by Gen-Z in their digital activism can also risk undermining their legitimacy as activists. When young people are the ones mobilising humour, they risk having their humour dismissed as “evidence of their developmental immaturity”.[xxxviii] This plays into broader critiques by older generations that Gen-Z lack respect for authority or nuanced understandings of the issues that they are protesting.[xxxix]

Conclusion

In the words of George Orwell, “every joke is a tiny revolution”.[xl]

The use of humour in activism has endured for centuries. Satire has long been a tool by activists to subvert traditional power structures, evade censorship, and highlight the absurdity of inequity. In many ways, Gen-Z are simply using the same playbook as those who came before them but simply via new media platforms and in new forms of content such as memes and TikToks. This exposes them to the same risks such as backlash, context collapse, and dismissal. However, it also exposes them to the same benefits – community, joy, and protection. I, for one, am excited to see where they go with this and how their jokes can possibly spark more “tiny revolutions”.

Personal reflections on the course

This course has been challenging for me. I had a serious personal issue that affected my ability to participate fully. Despite the incredible support of my group – Elias, Sara and Majlin – I felt I had to come back to the group earlier than I was ready. Nonetheless, I have enjoyed my topic immensely and found joy in exploring Gen-Z’s approach to digital activism even in the midst of my unbearable grief. Moreover, working with Elias, Sara and Majlin, has been rewarding and I’m proud of what we have achieved as a group. Both individually, and collectively, our blog content has been strong and added value to conversations about digital activism.

Bibliography

Bore Inger-Lise, K., Graefer, A., & Kilby, A. (2018). This Pussy Grabs back: Humour, Digital Affects and Women’s Protest [article]. Open Cultural Studies, 1(1), 529-540. https://doi.org/10.1515/culture-2017-0050

Branagan, M. (2007). Activism and the power of humour. Australian Journal of Communication, 34(1).

Cervi, L., & Marín-Lladó, C. (2022). Freepalestine on TikTok: from performative activism to (meaningful) playful activism. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 15(4), 414-434. https://doi.org/10.1080/17513057.2022.2131883

Chattoo, C. B., & Feldman, L. (2020). A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar. Oakland, California.

Denisova, A. (2019). Internet memes and society : social, cultural, and political contexts [Bibliographies Non-fiction]. Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,cookie,url,shib&db=cat05074a&AN=malmo.b2435946&site=eds-live&scope=site

Hall, S., Evans, Jessica and Nixon, Sean (Ed.). (2013). Representation. Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (Second ed.). Sage.

Hee, M., Jurgens, A.-S., Fiadotava, A., Judd, K., & Feldman, H. R. (2022). Communicating urgency through humor: School Strike 4 Climate protest placards. Journal of Science Communication, 21(5).

Jenkins, H., Shresthova, S., Gamber-Thompson, L., Kligler-Vilenchik, N., & Zimmerman, A. (2016). By Any Media Necessary : The New Youth Activism [Book]. NYU Press. https://proxy.mau.se/login?url=https://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&AuthType=ip,cookie,url,shib&db=nlebk&AN=1084160&site=eds-live&scope=site

Mayes, E., & Center, E. (2023). Learning with Student Climate Strikers’ Humour: Towards Critical Affective Climate Justice Literacies. Environmental Education Research, 29(4), 520-538. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2022.2067322

Mina, A. X. (2018). Memes to movements : how the world’s most viral media is changing social protest and power. Beacon Press.

Moreno-Almeida, C. (2021). Memes as snapshots of participation: The role of digital amateur activists in authoritarian regimes. New Media & Society, 23(6), 1545-1566. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820912722

Nissenbaum, A., & Shifman, L. (2018). Meme Templates as Expressive Repertoires in a Globalizing World: A Cross-Linguistic Study. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(5), 294-310. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcmc/zmy016

Showden, C. R., Barker-Clarke, E., Sligo, J., & Nairn, K. The connective is communal: hybrid activism in online & offline spaces. Social Movement Studies, 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2023.2171387

Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Yale University Press.

Vokes, R. (2018). Media and Development. Routledge.

Washington, K., & Marcus, R. (2022). Hashtags, memes and selfies: can social media and online activism shift gender norms? (ALIGN Report, Issue. https://www.alignplatform.org/resources/report-social-media-online-activism

Wielk, E., & Standlee, A. (2021). Fighting for Their Future: An Exploratory Study of Online Community Building in the Youth Climate Change Movement. Qualitative Sociology Review, 17(2), 22-37. https://doi.org/10.18778/1733-8077.17.2.02

Zulli, D., & Zulli, D. J. (2022). Extending the Internet meme: Conceptualizing technological mimesis and imitation publics on the TikTok platform. New Media & Society, 24(8), 1872-1890. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820983603

[i] Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Yale University Press. p.23

[ii] Jenkins, H. (2016). Youth Voice, Media, and Political Engagement. In H. Jenkins, S. Shresthova, L. Gamber-Thompson, N. Kligler-Vilenchik, & A. Zimmerman (Eds.), By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. NYU Press. p.7

[iii] Showden, C. R., Barker-Clarke, E., Sligo, J., & Nairn, K. The connective is communal: hybrid activism in online & offline spaces. Social Movement Studies, 1-20. p.1

[iv] Wielk, E., & Standlee, A. (2021). Fighting for Their Future: An Exploratory Study of Online Community Building in the Youth Climate Change Movement. Qualitative Sociology Review, 17(2), 22-37. p.23

[v] Jenkins, H. (2016). Youth Voice, Media, and Political Engagement. In H. Jenkins, S. Shresthova, L. Gamber-Thompson, N. Kligler-Vilenchik, & A. Zimmerman (Eds.), By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. NYU Press. p.37

[vi] Zulli, D., & Zulli, D. J. (2022). Extending the Internet meme: Conceptualizing technological mimesis and imitation publics on the TikTok platform. New Media & Society, 24(8), 1872-1890. P.1877

[vii] Nissenbaum, A., & Shifman, L. (2018). Meme Templates as Expressive Repertoires in a Globalizing World: A Cross-Linguistic Study. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(5), 294-310. P.295

[viii] Hall, S. (2013). The Work of Representation. In S. Hall, Evans, Jessica and Nixon, Sean (Ed.), Representation. Cultural Representations and Signifying Practices (Second ed., pp. 1 – 47). Sage. p.1

[ix] Ibid, p.294

[x] Washington, K., & Marcus, R. (2022). Hashtags, memes and selfies: can social media and online activism shift gender norms? ALIGN Report, London, ODI https://www.alignplatform.org/resources/report-social-media-online-activism

[xi] Vokes, R. (2018). Media and Development. Routledge. p.9

[xii] Nissenbaum, A., & Shifman, L. (2018). Meme Templates as Expressive Repertoires in a Globalizing World: A Cross-Linguistic Study. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 23(5), 294-310. p.306

[xiii] ibid

[xiv] Bore Inger-Lise, K., Graefer, A., & Kilby, A. (2018). This Pussy Grabs back: Humour, Digital Affects and Women’s Protest [article]. Open Cultural Studies, 1(1), 529-540. P.530

[xv] Branagan, M. (2007). Activism and the power of humour. Australian Journal of Communication, 34(1). P.42

[xvi] Chattoo, C. B., & Feldman, L. (2020). A Comedian and an Activist Walk into a Bar. Oakland, California. P90

[xvii] ibid

[xviii] Bore Inger-Lise, K., Graefer, A., & Kilby, A. (2018). This Pussy Grabs back: Humour, Digital Affects and Women’s Protest [article]. Open Cultural Studies, 1(1), 529-540. P.537

[xix] Branagan, M. (2007). Activism and the power of humour. Australian Journal of Communication, 34(1). p.50

[xx] ibid

[xxi] Bore Inger-Lise, K., Graefer, A., & Kilby, A. (2018). This Pussy Grabs back: Humour, Digital Affects and Women’s Protest [article]. Open Cultural Studies, 1(1), 529-540. P.535

[xxii] Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and Tear Gas: The Power and Fragility of Networked Protest. Yale University Press. p.29

[xxiii] Ibid, p.159

[xxiv] Ibid, p.161

[xxv] Mina, A. X. (2018). Memes to movements: how the world’s most viral media is changing social protest and power. Beacon Press. p.136

[xxvi] Cervi, L., & Marín-Lladó, C. (2022). Freepalestine on TikTok: from performative activism to (meaningful) playful activism. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 15(4), 414-434. P.428

[xxvii] Denisova, A. (2019). Internet memes and society: social, cultural, and political contexts, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.p.40

[xxviii] Moreno-Almeida, C. (2021). Memes as snapshots of participation: The role of digital amateur activists in authoritarian regimes. New Media & Society, 23(6), 1545-1566. P.1546

[xxix] ibid

[xxx] Denisova, A. (2019). Internet memes and society: social, cultural, and political contexts, Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group. p.343

[xxxi] Mina, A. X. (2018). Memes to movements: how the world’s most viral media is changing social protest and power. Beacon Press. p.86

[xxxii] Hee, M., Jurgens, A.-S., Fiadotava, A., Judd, K., & Feldman, H. R. (2022). Communicating urgency through humor: School Strike 4 Climate protest placards. Journal of Science Communication, 21(5). P.5

[xxxiii] Reilly, I. (2019). Exploring Humor and Media Hoaxing in Social Justice Activism Democratic Communique, 28(2). P.131

[xxxiv] Bore Inger-Lise, K., Graefer, A., & Kilby, A. (2018). This Pussy Grabs back: Humour, Digital Affects and Women’s Protest [article]. Open Cultural Studies, 1(1), 529-540. P.537

[xxxv] Mina, A. X. (2018). Memes to movements: how the world’s most viral media is changing social protest and power. Beacon Press. p.135

[xxxvi] Jenkins, H. (2016). Youth Voice, Media, and Political Engagement. In H. Jenkins, S. Shresthova, L. Gamber-Thompson, N. Kligler-Vilenchik, & A. Zimmerman (Eds.), By Any Media Necessary: The New Youth Activism. NYU Press. p.26

[xxxvii] ibid

[xxxviii] Mayes, E., & Center, E. (2023). Learning with Student Climate Strikers’ Humour: Towards Critical Affective Climate Justice Literacies. Environmental Education Research, 29(4), 520-538.p.522

[xxxix] ibid

[xl] Branagan, M. (2007). Activism and the power of humour. Australian Journal of Communication, 34(1).p.50